Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Before long, a trickle of muddy water is flowing through the gully, separating Forrester's army tent from the Indians' contraptions of tarpaulin and bamboo. A fire is out of the question and so the bearers are huddled together forlornly, squatting on their haunches like a gaggle of bidi-smoking birds. Moti Lal climbs the ridge to engage Forrester in another pointless conversation, then follows him back down the hill and crouches at the door of the tent. Finally Forrester is forced to give in and talk.

"So who exactly is your mistress?"

Moti Lal's face darkens.

She was always ungovernable, even before her mother died. Her father took no notice of her, whether she was good or bad, too busy weighing out coin to bother about the world outside his cloth-bound ledgers. The servants would come and report to him in the countinghouse, saying that the girl had thrown a cup at the porter, that she refused food, that she had been seen speaking to Bikaneri tribeswomen by the Cremation Gate. In the mornings her maid would find sand when she was combing her hair, as if she had spent the night out in the desert.

She was bringing shame on the family, and if the master chose to ignore it, the job of curbing her fell to his head clerk. At first Moti Lal used words. Then, when he found a cake of sticky black resin in her jewelry box, he dragged her into the courtyard and beat her with a carved stick kept for scaring away monkeys. She was locked in her room for three days. Distracted as he was finalizing a land deal, the master asked who was weeping in his house. Told it was Amrita, he seemed surprised. Does she want for something? he asked.

As soon as the bolt was drawn, she disappeared, returning with a wild look in her eye and garbled talk of trees and rushing water. Moti Lal could never find who brought the drug to her, and gradually she lost interest in everything else. She took to her bed, and stopped speaking. It was as if she had withdrawn to another world. He had to shake her and slap her face before she understood the news about her father.

His killer had left a length of wire wrapped tightly around his neck. The body had been found lying on a rubbish heap outside the town walls, the soles of its feet turned up at the sky like two pale fish. No one seemed surprised. Moneylenders are not popular people. Do you understand, Moti Lal shouted at her. Now you are completely alone.

Now the flood is coming. The earth will be drowned but like Manu the first man, Amrita will float on the ocean and be saved. She cups her hands and sees a little fish flip and curl in the rainwater. She will show it compassion because it is the Lord come to her as a sign, and though she is cold to the bone, the little horned fish means that she will survive.

They do not come to get her. The water saturates the palanquin, soaking the curtains and the cushions, running over the wooden frame in a constant stream. Amrita has no shawl, and the thin sari plastered over her skin offers no protection. She does not expect them to come. Moti Lal hates her and wants her dead. Why should he help her? She should move, but it will make no difference. The flood is imminent, and when it comes it will lift her up and sweep all of them away.

When it was time for the journey, Moti Lal had the haveli closed, and the valuables packed into trunks, which went on ahead with one of the servants. In the street, carts waited outside to take them to the railhead, three days journey by road. Shopkeepers sat by their scales and spat betel juice into the gutter, pointing out to each other the possessions of the murdered Kashmiri broker; his carpets, his scales. The bullocks swished their tails and the drivers scratched themselves. Everything was ready. And the girl would not go.

Moti Lal beat her and she lay on the floor and said she would kill herself. Moti Lal beat her again, and told her he did not care if she lived or died, but he had given his word to her uncle that he would bring her to Agra to be married. She said she had no uncle in Agra and marriage meant nothing to her because soon she would be dead. Moti Lal beat her until his arm was sore. When her face had puffed up and a tooth had loosened in her jaw she said she would go, but not by train. Finally, he gave in.

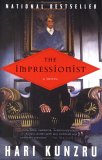

Reprinted from The Impressionist by Hari Kunzru by permission of Dutton, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002 by Hari Kunzru. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.