Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

In 1918 Agra is a city of three hundred thousand people clenched fist-tight around a bend in the River Jumna. Wide and lazy, the river flows to the south and east, where eventually it will join with the Ganges and spill out into the Bay of Bengal. This, just one of countless towns fastened to its banks, is an anthill of traders and craftsmen that rose out of obscurity around five hundred years before, when the Mughals, arriving from the north, settled on it as a place to build tombs, paint miniatures, and dream up new and bloody modes of war.

If, like the flying ace Indra Lal Roy, you could break free of gravity and view the world from up above, you would see Agra as a dense, whirling movement of earth, a vortex of mud bricks and sandstone. To the south this tumble of mazy streets slams into the military grid of the British cantonment. The Cantonment (gruffly contracted to Cantt. in all official correspondence) is made up of geometric elements like a child's wooden blocks; rational avenues and parade grounds, barracks for the soldiers who enforce the law of His Britannic Majesty George. To the north this military space has a mirror in the Civil Lines, rows of whitewashed bungalows inhabited by administrators and their wives. The hardness of this second grid has faded and softened with time, past planning wilting gently in the Indian heat.

Agra's navel is the fort, a mile-long circuit of brutal red sandstone walls enclosing a confusion of palaces, mosques, water tanks, and meeting halls. A railway bridge runs beside it, carrying passengers into the city from every part of India. The bustling crowd at Fort Station never thins, even in the small hours of the morning. The crowd is part of the grand project of the railway, the dream of unification its imperial designers have engineered into reality. The trails of boiler smoke that rise over heat-hazy fields and converge on the station's packed platforms are part of a continent-wide piece of theater. Like the one hundred and three tunnels blasted through the mountains up to Simla, the two-mile span of the Ganges bridge in Bihar, and the one-hundred-and-forty-foot piles driven into the mud of Surat, the press of people at the station proclaims the power of the British, the technologists who have all India under their control.

For such a lively city, Agra is heavily marked by death. This is largely the fault of the Mughals, who, in contrast to the current mechanically minded set of masters, thought hard about the next life and the things that get lost in the transition from this one. Everywhere they have left cavernous mosques, chilly monuments to absence. Around the curve of the river from the fort is the Taj Mahal. For all its massive marble beauty, for all the relief its cold floor and dark interior affords on a scorching day, it is a melancholy place, forty million rupees' and who knows how many lives' worth of autocratic mourning. The Emperor Shah Jahan loved Mumtaz-i-Mahal. Now the pain of his loss rises up at the edge of town, clothed in the work of countless hands, surrounded by a formal garden still used as a meeting place by steam-age lovers. Despite all this effort love still refuses to conquer, and the trysting couples have a subdued, pensive look about them.

Now, as it does every so often, death has come to hang over the city. This time the killer is not siege or famine, but the influenza epidemic, making its way eastward across the world from its mystical birth in a pile of dung behind an American army camp. By the time it leaves it will have taken with it a third of Agra's people; a third of all the shoemakers, potters, silk weavers, and metalworkers in the bazaars; a third of the women pounding their washing against flat stones by the riverbank; a third of the six hundred hands at John's ginning mill; a third of the convicts making rugs in the city jail; a third of all the farmers bringing produce in to market; a third of the porters sleeping on the station platform between shifts; a third of the little boys playing shin-shattering games of cricket, bowling yorkers off the baked mud of their tenement courtyards. Rajputs, Brahmins, Chamars, Jats, Banias, Muslims, Catholics, members of the Arya Samaj, and communicants of the Church of England will all succumb to the same sequence of fatigue, sweating, fever, and darkness.

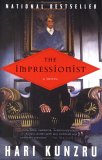

Reprinted from The Impressionist by Hari Kunzru by permission of Dutton, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002 by Hari Kunzru. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.