Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Readalikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Gita the servant girl has no idea of her peril. Her eye has been caught by a monkey, and she is thinking how nice it would be if it spoke. Perhaps the monkey has been sent by her prince to watch over her, and perhaps it will grow to an enormous size and put her on its furry shoulder and carry her off to a palace where there will be a wedding with singers and dancing-or if not a prince then at least the monkey could turn into the pretty boy who cleans for the fat bania druggist, or if not a shape-changing monkey then a talking monkey who could tell her fortune, and if not a fortune-telling monkey then one which would do something more to distract her from her aching back than just sitting there, scratching its lurid red bottom and rolling its lips backward and forward over its nasty teeth. She straightens up and wipes a hand over her forehead. As usual there is more work to do.

For its part, the monkey has no intention of changing shape. Lacking royal connections or powers of augury, its primary interest is the strong onion smell wafting under its nostrils. Onions are edible. It sits on a crumbling section of wall and cocks its head at a shape it has spotted moving about in an open doorway, unable to decide whether it, too, is edible, or perhaps dangerous.

The shape is Anjali the maid, and she is trying to stay out of sight. It is lucky she came. Something told her, a creaking in her bones, that she should keep a close eye on her daughter today. Look at the filthy boy! If he touches so much as a hair on little Gita's head, he will pay for it. This is not an idle threat. Anjali the maid knows things about Pran Nath Razdan. In fact she knows rather more than he does himself. Just one touch, and she will tell.

Anjali was brought up in the moneylender's house at the edge of the desert. Some years older than the moneylender's daughter, she had been placed with the family as a maid as soon as she was old enough to plait hair and wield a flatiron. She watched her young mistress withdraw from the world, and tended to her as she lay inert on her bed, transfixed by the invisible objects of her imagination. Among the servants Amrita's madness was said to be of that very holy type that reveals the illusory nature of the world. Some of the women would even contrive to touch her clothing when they brought her tea. Anjali was not one of them. She found the girl frightening. Trying to get her to take a sip of water or a mouthful of dhal, she would stretch her arm out straight, keeping herself as far from the bed as she could, on guard against evil spirits that might jump from the afflicted body to hers. When she was told she would be accompanying her on the journey to Agra, the first thing she did was consult a palmist, who told her to beware of water.

Perhaps it was this advice that saved her. After the flash flood she and two of the porters were the only ones still left alive, or so they thought. Searching for other survivors, they waded down a gulley until they found a dacoits' cave, with Amrita sitting outside it, dressed in a khaki shirt and a pair of shorts. They pulled the Englishman's naked body out of the mud a few miles farther south. It was not hard to imagine what had happened.

Amrita mumbled poetry words about trees, and about the water. Anjali dressed her in a sari and made her decent, repeating charms to ward off the evil eye. Inside the shirt pocket was an illegible document, with a photograph of the dead Englishman. She slipped the picture discreetly into her skirts. Once they finally reached Agra, pulling into Fort Station on the third-class carriage of the train, she lost no time in breaking the shocking news to the servants of her new household. The girl had polluted herself. Surely she would have to be sent away.

In the uncle's house the girl was locked in an upstairs room, while the uncle held meetings with brothers and cousins. Then one of them summoned Anjali and gave her a silver bangle, a nose stud, and a pair of heavy earrings. She understood that she was to keep her mouth shut. They had found a husband for Amrita, a Razdan, and they would not tolerate any impediment to the marriage. Had anyone asked her opinion, Anjali would have said she thought it was an ill-fated match. She had often seen the girl naked. She had examined her closely, and she had a mole on her stomach, right at the very center just under her breasts. The meaning, as she whispered to the mali, was clear. The new bride would die young.

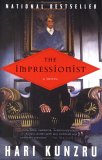

Reprinted from The Impressionist by Hari Kunzru by permission of Dutton, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc. Copyright © 2002 by Hari Kunzru. All rights reserved. This excerpt, or any parts thereof, may not be reproduced without permission.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.