Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

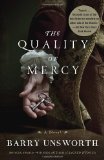

A Novel

by Barry UnsworthThis article relates to The Quality of Mercy

What makes a writer turn to historical fiction? The task of creating a fictional world is hard enough, so why throw in the additional labor of intensive research and the mental calisthenics of imagining another time? Some of the genre's biggest names respond...

Before his death in June 2012, Barry Unsworth's literary imagination covered a broad territory in both time and space, from fourteenth-century England (Morality Play), to the end of the Ottoman Empire (Pascali's Island), to ancient Greece (The Songs of the Kings) and eighteenth-century England (The Quality of Mercy). Unsworth credited living in historically rich places like Greece and Turkey (and now Italy) with awakening his "wonder at the constant sense of continuity and connection" between past and present. In a 2008 interview with Littoral, he explains:

Before his death in June 2012, Barry Unsworth's literary imagination covered a broad territory in both time and space, from fourteenth-century England (Morality Play), to the end of the Ottoman Empire (Pascali's Island), to ancient Greece (The Songs of the Kings) and eighteenth-century England (The Quality of Mercy). Unsworth credited living in historically rich places like Greece and Turkey (and now Italy) with awakening his "wonder at the constant sense of continuity and connection" between past and present. In a 2008 interview with Littoral, he explains:

Nowadays I go to Britain relatively rarely and for short periods; in effect, I have become an expatriate. The result has been a certain loss of interest in British life and society and a very definite loss of confidence in my ability to register the contemporary scene there - the kind of things people say, the styles of dress, the politics, etc - with sufficient subtlety and accuracy. So I have turned to the past. The great advantage of this, for a writer of my temperament at least, is that one is freed from a great deal of surface clutter. One is enabled to take a remote period and use it as a distant mirror... and so try to say things about our human condition - then and now - which transcend the particular period and become timeless.

Unsworth set historical fiction apart from the writing of history as a (nonfiction) discipline - a novel's goals are in the realm of art, not fact:

Writers of historical fiction are not under the same obligation as historians to find evidence for the statements they make. For us it is sufficient if what we say can't be disproved or shown to be false. We are quite at ease in this no man's land of ignorance and doubt and dispute, absorbed in the ambiguities of trying to reach truth by mixing fact with invention. The search for truth in historical fiction - in fiction of any kind - is really a search for intensity of illusion. If this is achieved, the events and characters will take on a deeper reality than could ever be achieved by fidelity to the facts of the matter.

In an essay for The Guardian, Hilary Mantel, author of the Booker-Prize winning novel Wolf Hall (2010), enters with gusto into the "time-worn debate about the value of historical fiction":

In an essay for The Guardian, Hilary Mantel, author of the Booker-Prize winning novel Wolf Hall (2010), enters with gusto into the "time-worn debate about the value of historical fiction":

The boundaries of the term 'historical fiction' are now so wide that it's almost meaningless, so use of the term is beginning to look like an accusation, a stick to beat writers with: you're historical, you weaselly good-for-nothing, you luxury, you parasite. The accusation is that authors are ducking the tough issues in favour of writing about frocks... It's as if the past is some feathered sanctuary, a nest muffled from contention and the noise of debate, its events suffused by a pink, romantic glow. But this is not how, in practice, modern novelists see their subject matter. If anything, the opposite is true.

History offers us vicarious experience. It allows the youngest student to possess the ground equally with his elders; without a knowledge of history to give him a context for present events, he is at the mercy of every social misdiagnosis handed to him. The old always think the world is getting worse; it is for the young, equipped with historical facts, to point out that, compared with 1509, or even 1939, life in 2009 is sweet as honey. Immersion in history doesn't make you backward-looking; it makes you want to run like hell towards the future.

Why do it, then?

"Writers' motives are as varied as criminals', but I suspect that the historical novelist's genetic code contains the geeky genes of the model-maker - there is pleasure to be had in the painstaking reconstruction of a lost world."

Mitchell finds a paradox at work in the nature of a project called "historical fiction"; "the 'historical' half demands fidelity to the past, whilst the 'fiction' half requires infidelity - people must be dreamt up, their acts fabricated, and the lies of art must be told."

A.S. Byatt, (The Children's Book, 2009), is the author of a book of essays exploring the tradition of historical fiction (On Histories and Stories: Selected Essays, 2000). She sees a cross-pollination at work between present and past: "In many ways if you write a novel about the past, you find yourself saying more about... the habits of mind of the present than if you take the present head on."

A.S. Byatt, (The Children's Book, 2009), is the author of a book of essays exploring the tradition of historical fiction (On Histories and Stories: Selected Essays, 2000). She sees a cross-pollination at work between present and past: "In many ways if you write a novel about the past, you find yourself saying more about... the habits of mind of the present than if you take the present head on."

Best-selling author Diana Gabaldon (A Breath of Snow and Ashes, 2005) offers a candid take on the practical advantage of historical fiction for the beginning novelist: "I chose to write historical fiction for my first (practice) novel, because I was a research professor (albeit in the sciences). I knew my way around a library, and said, 'It seems easier to look things up than to make them up - and if I turn out to have no imagination, I can steal things from the historical record.'"

Best-selling author Diana Gabaldon (A Breath of Snow and Ashes, 2005) offers a candid take on the practical advantage of historical fiction for the beginning novelist: "I chose to write historical fiction for my first (practice) novel, because I was a research professor (albeit in the sciences). I knew my way around a library, and said, 'It seems easier to look things up than to make them up - and if I turn out to have no imagination, I can steal things from the historical record.'"

Filed under Books and Authors

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Quality of Mercy. It originally ran in February 2012 and has been updated for the

August 2012 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Quality of Mercy. It originally ran in February 2012 and has been updated for the

August 2012 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.