Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

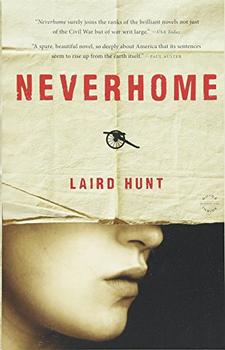

A Novel

by Laird HuntThis article relates to Neverhome

Historians have documented some 400 cases of women serving as men in the American Civil War (see our review and Beyond the Book for Liar, Temptress, Solider, Spy).

Motives for their enlistment varied widely, although it would seem that most enlisted to stay with family; many were concerned that their husband, father, brother or son would die in the conflict and remain unknown or unburied. Some chose to adopt an assumed identity out of patriotism or on moral grounds, as slavery was often deemed offensive to God or, on the other side of the conflict, to be God's intention. One young woman from Brooklyn named Emily believed she was the reincarnation of Joan of Arc and so joined up in the heat of religious fervor. Economics was also a motivating factor; a soldier's pay was considerably better than professions open to women (maids, for example, earned $4 to $7 per month while a Union solder received $13). Harriet Merrill enlisted with the 59th New York Infantry to leave behind the brothel in which she worked.

Today it's difficult to imagine how these women could have remained undetected for months or years, but the military was vastly different 150 years ago. Physical exams during enlistment, for example, were cursory; often a soldier merely had to show he had enough fingers to pull the trigger on a gun and enough teeth to rip open a Minie ball cartridge. (Sarah Edmonds said her exam consisted of a "firm handshake.") Both armies accepted very young men into their ranks as well (the Confederacy had no lower age limit by the end of the war), and so having a high voice and no beard wouldn't have been unusual. Hygiene habits of the Civil War soldier (officers and enlisted alike) also contributed to the women's ability to blend in: Everyone slept in all their clothes, including their boots; they frequently took care of bodily functions in private; and bathing occurred rarely (i.e., every few months). Menstrual cycles were handled with rags, and bloody cloths around a Civil War encampment would have been a regular sight.

Today it's difficult to imagine how these women could have remained undetected for months or years, but the military was vastly different 150 years ago. Physical exams during enlistment, for example, were cursory; often a soldier merely had to show he had enough fingers to pull the trigger on a gun and enough teeth to rip open a Minie ball cartridge. (Sarah Edmonds said her exam consisted of a "firm handshake.") Both armies accepted very young men into their ranks as well (the Confederacy had no lower age limit by the end of the war), and so having a high voice and no beard wouldn't have been unusual. Hygiene habits of the Civil War soldier (officers and enlisted alike) also contributed to the women's ability to blend in: Everyone slept in all their clothes, including their boots; they frequently took care of bodily functions in private; and bathing occurred rarely (i.e., every few months). Menstrual cycles were handled with rags, and bloody cloths around a Civil War encampment would have been a regular sight.

It's generally agreed that the biggest aid to concealment was the Victorian attitudes of the day. Gender roles were rigidly defined during the era and seeing a woman in men's clothing doing a man's job would have been unthinkable. Men in particular were instilled with preconceived notions about female physical, emotional and intellectual abilities and were consequently predisposed to see the female recruits as other men; the idea that their fellow soldiers were women wouldn't have occurred to most of them. Indeed, when a woman soldier's identity was revealed, they were most often accused of being either mentally ill or a prostitute. Cousins Mary and Mollie Bell (Privates Bob Martin and Tom Parker, respectively) were sent to Castle Thunder Prison for three weeks when the general under whom they'd served valiantly for two years discovered their genders.

Some commanding officers were completely aware of the fact that some of their soldiers were women and simply chose to look the other way. In fact, the captain the Bell cousins reported to knew they were women and was reprimanded for allowing them to stay in the ranks.

Injury or illness often resulted in the soldiers' genders being revealed, although female nurses and nuns helping in the military hospitals frequently opted to not report their patient's secret. Sometimes the women chose to admit the truth, either hoping to be discharged or believing that the person they told would not reveal their identities (some did, some didn't). Some were discovered by an inability to disguise their overt femininity – for example one woman was exposed after someone threw an apple at her which she attempted to catch in her (non-existent) apron. An unknown number of women were never discovered, however, going to their graves masquerading as men and buried as men in their army uniforms. Sarah Rosetta Wakeman was one such soldier, buried during the war as Private Lyons Wakeman in Chalmette National Cemetery for more than a century. Her identity and fate weren't revealed until relatives discovered 30 letters she'd written from the war stored in a trunk in their attic.

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Neverhome. It originally ran in September 2014 and has been updated for the

May 2015 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Neverhome. It originally ran in September 2014 and has been updated for the

May 2015 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.