Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Plague Land

As Oswald, the hero of Plague Land tells it, most fourteenth-century medical practices were hit-or-miss experiments, with the misses resulting in dead patients and blood everywhere. The spread of the Great Mortality (Bubonic plague, or as it was later known, "The Black Death") inspired all manner of medical trial and error, as Europe struggled to stay ahead of the speedy and deadly epidemic.

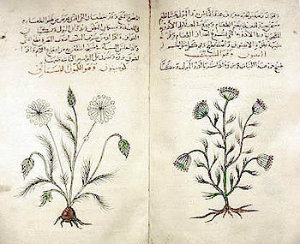

Herbal medicine was often the first, and the last, line of defense available. Herbs were expected to function in a basic capacity as a sort of aromatherapeutic defense against contagion. If sickness came from bad air, a pomander or posy of good-smelling stuff like cloves, lemon balm, or mint just might keep it at bay. If you couldn't smell it, maybe it couldn't hurt you. While this practice was likely not very effective, other herbal treatments had at least a chance of helping the sick. A poultice of garlic could have a natural antibiotic effect, and a rosehip tincture could deliver a whopping dose of vitamin C. Knowledge of herbs came both from the classical sources preserved and studied in monasteries (sources like the Greek Dioscorides herbal encyclopedia, De Materia Medica) and from local herbariums. Herbal medicine had a democratic component – any villager could gather wild plants. While plant-based medicine didn't do much to slow the spread of the plague, it probably provided some comfort to survivors – and didn't cause as much suffering as other more aggressive medical interventions.

Herbal medicine was often the first, and the last, line of defense available. Herbs were expected to function in a basic capacity as a sort of aromatherapeutic defense against contagion. If sickness came from bad air, a pomander or posy of good-smelling stuff like cloves, lemon balm, or mint just might keep it at bay. If you couldn't smell it, maybe it couldn't hurt you. While this practice was likely not very effective, other herbal treatments had at least a chance of helping the sick. A poultice of garlic could have a natural antibiotic effect, and a rosehip tincture could deliver a whopping dose of vitamin C. Knowledge of herbs came both from the classical sources preserved and studied in monasteries (sources like the Greek Dioscorides herbal encyclopedia, De Materia Medica) and from local herbariums. Herbal medicine had a democratic component – any villager could gather wild plants. While plant-based medicine didn't do much to slow the spread of the plague, it probably provided some comfort to survivors – and didn't cause as much suffering as other more aggressive medical interventions.

The stereotypical gruesome medical practices of the past were well in place by the fourteenth century – bloodletting, trepanning, and surgery without anesthesia. Lancing the "buboes" – the swollen infected lymph nodes symptomatic of bubonic plague – was a popular, if painful (and ineffective) strategy. The goal of these invasive sorts of treatments was to release the contagion from the body – whether it was an evil humor or something more supernatural. Because the plague was so widespread and fast-moving, it looked very much to the medieval mind like a judgment from God or, conversely, a trick of the devil. Causing suffering, then, was a potentially helpful side effect of medical treatment. If the patient could show contrition in the face of the Almighty, he might be spared. And as S.D. Sykes suggests in Plague Land, there was a booming market in Papal Indulgences, mystic talismans, and holy relics, which were thought to work as spiritual preventive medicine.

Did medieval Europe find anything that worked to slow the plague? Even though the idea of contagion was very poorly understood at the time, the mechanics of the plague's transmission must have become very obvious: have contact with plague victims and their belongings, get sick very soon. Medical advice from the classical world was helpful up to a point. Classical physicians like Hippocrates and Galen offered nuggets of wisdom, like the adage (rendered in Latin) "Cito, Longe, Tarde" – "Leave quickly, go far away and come back slowly." This kind of thinking led, eventually, to measures that actually did help, like sanitation and the prompt burial of victims. Cities in Italy led the way by establishing hygienic practices to stem the epidemic, from isolating victims and their families to quarantining ships at port. Public health policy, more than any medical practice, was the most effective innovation to come out of the epidemic.

Did medieval Europe find anything that worked to slow the plague? Even though the idea of contagion was very poorly understood at the time, the mechanics of the plague's transmission must have become very obvious: have contact with plague victims and their belongings, get sick very soon. Medical advice from the classical world was helpful up to a point. Classical physicians like Hippocrates and Galen offered nuggets of wisdom, like the adage (rendered in Latin) "Cito, Longe, Tarde" – "Leave quickly, go far away and come back slowly." This kind of thinking led, eventually, to measures that actually did help, like sanitation and the prompt burial of victims. Cities in Italy led the way by establishing hygienic practices to stem the epidemic, from isolating victims and their families to quarantining ships at port. Public health policy, more than any medical practice, was the most effective innovation to come out of the epidemic.

Contemporary scientists are still at work analyzing the plague in an effort to better prepare for future epidemics. A recent study has mined climatological data to come up with a new explanation for the rapid spread of the disease – it wasn't black rats, after all, who spread the germ via their fleas, but gerbils, taking advantage of a warm and wet spell to run amok.

Picture of Medieval woodblock print - The Black Death by Bettmann/Corbis

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Plague Land. It originally ran in March 2015 and has been updated for the

April 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Plague Land. It originally ran in March 2015 and has been updated for the

April 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.