Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

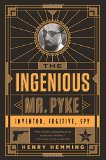

Inventor, Fugitive, Spy

by Henry HemmingThis article relates to The Ingenious Mr. Pyke

Geoffrey Pyke, the subject of The Ingenious Mr Pyke, was a man of many talents; his interests were as varied as they were obsessive. To understand them, we need look no further than two of his most successful projects, The Malting House School and the development of a remarkable substance which became known as "pykrete."

The Malting House School was a radical new approach to teaching based on the emerging science of psychoanalysis. The impetus for its creation was the birth of Pyke's only son, David. Concerned about the limitations of what he perceived to be an unenlightened English educational system, Pyke (characteristically undeterred by the fact that he had no previous experience either in teaching or child psychology), founded the kindergarten in Cambridge in 1924 following a period of intensive research. To aid him in his task, this unlikely pedagogist hired Susan Isaacs, a thirty-nine-year old psychologist. Together with another teacher, Evelyn Lawrence, who joined the kindergarten in 1927, they would conduct what Hemming describes as "one of the boldest experiments in pre-school education anywhere in the world."

Avoiding the traditional disciplinarian style of teaching, Pyke and Issac's school was a non-coercive, laissez-faire environment which encouraged children's natural curiosity and creativity. The Malting House approach to education was underpinned by Freudian theories, as well as well as the developmental concepts of contemporary cognitive behaviorist, Jean Piaget. Other influences included Rousseau's philosophy, sociology, and contemporary psychology. It was Pyke's firm belief that "each of us arrives into the world as a scientist in the making, that as children we are naturally inquisitive and will conduct experiments in order to understand the world around us." Teachers took on the role of "co-investigators" aiding the children in self-driven discoveries. Everything that transpired at Malting House was painstakingly and exhaustively recorded, a fact that proved crucial to its legacy.

Avoiding the traditional disciplinarian style of teaching, Pyke and Issac's school was a non-coercive, laissez-faire environment which encouraged children's natural curiosity and creativity. The Malting House approach to education was underpinned by Freudian theories, as well as well as the developmental concepts of contemporary cognitive behaviorist, Jean Piaget. Other influences included Rousseau's philosophy, sociology, and contemporary psychology. It was Pyke's firm belief that "each of us arrives into the world as a scientist in the making, that as children we are naturally inquisitive and will conduct experiments in order to understand the world around us." Teachers took on the role of "co-investigators" aiding the children in self-driven discoveries. Everything that transpired at Malting House was painstakingly and exhaustively recorded, a fact that proved crucial to its legacy.

Ultimately, the Malting House School was a short-lived endeavor – despite receiving plaudits from leading child psychologists of the day, including Melanie Klein and Jean Piaget himself, the institution was a commercial failure. Perennially short of money, continued funding became impossible when Pyke was declared bankrupt. The Malting House School closed its doors in July 1929. Its influence, however, would prove to be much longer-lasting. The information gathered and recorded by the teachers inspired generations of educational reformers, and formed the basis of future development in educational theory. The data was also used by Susan Isaacs, who would go on to become one of the leading experts in the field, in her hugely influential books, Social Development in Young Children and Intellectual Growth in Young Children.

While Isaacs continued to devote her time to child psychology, the demise of the Malting House School marked the end of Pyke's career in education. With the rise of fascism in Europe, and the eventual outbreak of World War Two in 1939, another career path beckoned – that of military inventor. Having charmed his way into a high-level position in Combined Operations, a secretive war department, Pyke's febrile inventive mind was given free rein by the department's commander, Lord Louis Mountbatten, who recognized the genius in Pyke's seemingly ridiculous inventions. Among these was Pyke's proposal to build a berg-ship – that is a ship, or more precisely an aircraft carrier, made entirely of reinforced ice which, he believed, would turn the tide of the Battle of the Atlantic in the Allies' favor (the Germans, at the time, had gained supremacy in the Atlantic with their U-boats wreaking havoc on the shipping lanes between North America and Britain).

The germ for this inspired idea came from Pyke's knowledge that planes had sometimes been known to perform emergency landings on the top of icebergs. Pure ice, however, was not solid or stable enough to function as giant runways. But what if ice could be strengthened? Pyke set himself the task of customizing icebergs and eventually hit on the realization that ice mixed with wood pulp would be "weight for weight as strong as concrete." Both Mountbatten and Churchill were enamored with the idea of this new material known as pykrete, and invested significant resources in the development of the project. Once again, however, Pyke was to be frustrated in the execution of his grand plan. During the development and testing phase of the pykrete berg-ships project (codenamed "Habbakuk"), other factors tilted the balance of the war in the Allies' favor, and Pyke's idea was never put into action as he had envisaged it. His concept was far from wasted; it inspired the idea of a floating harbor which was used to great effect during the D-Day landings and pykrete was used in the laying of an oil supply pipeline under the English Channel.

From revolutionary educational reformer to military machine mastermind, Mr. Pyke was indeed, nothing if not ingenious.

Picture of Malting House School by Keith Edkins from Geograph

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Ingenious Mr. Pyke. It originally ran in June 2015 and has been updated for the

September 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Ingenious Mr. Pyke. It originally ran in June 2015 and has been updated for the

September 2016 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

When a true genius appears in the world, you may know him by this sign...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.