Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to An Unrestored Woman

At the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, Britain withdrew from India and the country split into two so as to form an independent Muslim country to the north-east and north-west of India. Although the British withdrew essentially without incident, the decision to partition India set off a tsunami of violence and what is considered the largest single episode of human migration in history. Somewhere between 12 and 15 million people—depending on the source—abandoned their generational homelands and fled, Muslims to West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and non-Muslims, including Hindus, Sikhs, and Christians, to India. Between 1 and 2 million people were murdered, and approximately 75,000 women were kidnapped, raped, and mutilated. Partition remains one of the defining moments in Indian and Pakistani culture, leaving deep trans-generational wounds. In his article in The New Yorker, William Dalrymple states, "Partition is central to modern identity in the Indian subcontinent, as the Holocaust is to identity among Jews, branded painfully onto the regional consciousness by memories of almost unimaginable violence."

At the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, Britain withdrew from India and the country split into two so as to form an independent Muslim country to the north-east and north-west of India. Although the British withdrew essentially without incident, the decision to partition India set off a tsunami of violence and what is considered the largest single episode of human migration in history. Somewhere between 12 and 15 million people—depending on the source—abandoned their generational homelands and fled, Muslims to West and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh), and non-Muslims, including Hindus, Sikhs, and Christians, to India. Between 1 and 2 million people were murdered, and approximately 75,000 women were kidnapped, raped, and mutilated. Partition remains one of the defining moments in Indian and Pakistani culture, leaving deep trans-generational wounds. In his article in The New Yorker, William Dalrymple states, "Partition is central to modern identity in the Indian subcontinent, as the Holocaust is to identity among Jews, branded painfully onto the regional consciousness by memories of almost unimaginable violence."

British traders first arrived on the Indian subcontinent in the early 1600s. By 1765 they were in effective control of much of the country, although the official period of rule known as the Raj did not begin until 1858. As colonial power was consolidated, a growing middle class of Indians, having received an English education, filled the lower echelon civil service positions in the Crown's administration. These educated Indians became increasingly dissatisfied with the condescension and contempt expressed toward them by many of the British, and they began to press for greater self-governance. On December 28, 1885, "a group of 72 social reformers, journalists and lawyers convened for the first meeting of The Indian National Congress." This organization emerged as the prominent voice for social justice and the nascent Indian Independence Movement. The All-India Muslim League was formed in 1906 with the goal of protecting and advancing Muslim rights. Initially the League supported a united India, but with time, demands for a separate Muslim nation increased.

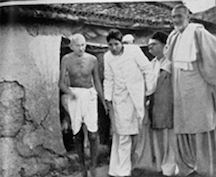

Large numbers of Indian troops fought for Britain in World War I, and the lack of recognition fueled demands for social justice and self-rule. In 1915, Mohandas Karamchand (Mahatma) Gandhi returned from South Africa, where he had participated in the anti-apartheid movement. He became a leading figure in the Independence Movement and a key member of the Indian National Congress. As protests grew, British response became more violent. In 1919, General Dyer ordered his troops to open fire on peaceful demonstrators in Amritsar; and in 1930, during the Dandi Salt March (a massive demonstration of civil disobedience led by Mahatma Gandhi) demonstrators were clubbed, and many, including Gandhi, were arrested.

Three prominent leaders to emerge from the Indian Independence Movement were Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, who would become India's first Prime Minister, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah, leader of the Muslim League and Pakistan's first governor general. All were English educated lawyers. Jinnah's initial intent was to work within the Hindu dominated National Congress, but by the 1940s, his relationship with Gandhi had deteriorated into intense mutual animosity, and Jinnah began speaking out for an independent Muslim homeland.

Relations between the Hindus and Muslims had been generally peaceful until the early twentieth century. In his New Yorker article, Dalrymple states, "In the nineteenth century, India was still a place where traditions, languages and cultures cut across religious groupings, and where people did not define themselves primarily through their religion." Many writers, including Alex von Tunzelmann in her book Indian Summer, which Dalrymple quotes, blame the unraveling of good relations on colonial rule and its insistence, "to define communities based on religious identity and attach political representation to them." Other theories, he states, blame the deterioration on more personal factors, most notably, "the clash of personalities among the politicians of the period, particularly between Muhammad Ali Jinnah … Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru."

Relations between the Hindus and Muslims had been generally peaceful until the early twentieth century. In his New Yorker article, Dalrymple states, "In the nineteenth century, India was still a place where traditions, languages and cultures cut across religious groupings, and where people did not define themselves primarily through their religion." Many writers, including Alex von Tunzelmann in her book Indian Summer, which Dalrymple quotes, blame the unraveling of good relations on colonial rule and its insistence, "to define communities based on religious identity and attach political representation to them." Other theories, he states, blame the deterioration on more personal factors, most notably, "the clash of personalities among the politicians of the period, particularly between Muhammad Ali Jinnah … Mohandas Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru."

During World War II, tensions between Hindus and Muslims turned violent, exacerbated by differences between the National Congress and the Muslim League. While Britain's troops (including 2.5 million Indian soldiers, all volunteers) waged battle on three continents, campaigns of civil disobedience and violence against colonial rule intensified in India. In response to the Quit India Resolution launched by the National Congress in 1942, Britain jailed many of the Congress's leaders, including Gandhi and Nehru. Episodic violence between Hindus and Muslims escalated as it became clear that some form of power transfer from the British - stretched thin by the war effort and the growing unrest - to the Indians was inevitable. Jinnah took advantage of the power vacuum to strengthen his position as leader of the Muslim League. In August 1946, he called for a day of "Direct Action" to protest a Hindu majority in a negotiated interim government. Although his stated intention was for peaceful protest, events turned violent. In August, protests in Calcutta led to four days of retributive violence that left more than 5,000 Hindus and Muslims dead and 15,000 wounded.

As religious-based violence spread, the British, afraid that tensions would escalate into civil war, orchestrated their withdrawal. On February 20, 1947, the British Prime Minister stated that British rule would come to an end no later than June 1948. In March 1947, Lord Louis Mountbatten arrived to finalize the transfer of power. On June 3, 1947, he announced the British government's agreement that India would be partitioned on the day of independence, and that independence would take place ten months earlier than stated, on August 15, 1947.

The scale and ferocity of mass violence that erupted at the moment of Independence likely resulted from the hasty and poorly conceived manner in which Partition was executed. Sir Cyril Radcliffe, a London judge with no knowledge of India's demographics and no map-making experience, arrived in India for the first and only time on July 8, 1947 charged with – in five weeks – equitably dividing the huge territory of India. The result was the Radcliffe line, an arbitrary border that divided villages, farms, and even houses. It split Pakistan into two areas, East and West Pakistan, separated by 1,000 miles of India. Dalrymple quotes Jinnah as stating, "[the country of Pakistan is] a maimed, mutilated, and moth-eaten travesty" that would be, "sowing the seeds of future serious trouble." From The Hidden Story of Partition and its Legacies: "90% of the subcontinent's industry, and taxable income base remained in India, including the largest cities of Delhi, Bombay and Calcutta," while, "Pakistan won a poor share of the colonial government's financial reserves - with 23% of the undivided land mass, it inherited only 17.5% of the former government's financial assets."

Within hours, flames rose across the countryside, and waves of panicked people set off on long and perilous journeys toward safer territory. Retributive violence spiraled out of control. Women suffered a particularly brutal fate. Between 75,000, and 100,000 were kidnapped, raped, tortured, and mutilated. Some either voluntarily committed suicide or were murdered by male relatives to avoid the shame. Families often turned away survivors, as "tainted" women lacked financial value. Palash Ghosh, in her article on rape and Partition quotes Urvashi Butalia, an Indian feminist, as saying that some women were sold into prostitution, "some were sold from hand to hand, some were taken as wives and married by conversion. And some just disappeared."

Within hours, flames rose across the countryside, and waves of panicked people set off on long and perilous journeys toward safer territory. Retributive violence spiraled out of control. Women suffered a particularly brutal fate. Between 75,000, and 100,000 were kidnapped, raped, tortured, and mutilated. Some either voluntarily committed suicide or were murdered by male relatives to avoid the shame. Families often turned away survivors, as "tainted" women lacked financial value. Palash Ghosh, in her article on rape and Partition quotes Urvashi Butalia, an Indian feminist, as saying that some women were sold into prostitution, "some were sold from hand to hand, some were taken as wives and married by conversion. And some just disappeared."

The trauma of Partition now affects at least three generations. The conflict over Kashmir continues; since Partition, four wars have been fought between the two nations, and leaders on both sides continue to fan the flames for political gain. However, trauma also inspires creative expression as a means to bear witness. Just as the Holocaust spawned generations of artistic endeavor, so, too, Indians and Pakistanis attempt to make sense of the horrors of Partition through art. Shobha Rao is one of a growing list. Below is a small sampling of other art inspired by Partition.

Literature, Installation Art, and Films on Partition

A Visual History of the India-Pakistan Partition by Aanchal Malhorti

Short stories by Saadat Hasan Manto

Earth, film by Deepa Mehta

Cracking India, a novel by Bapsi Sidhwa (the film Earth was based on this)

Midnight's Children by Salman Rushdie

"The Seer of Pakistan," essay on Manto in The New Yorker by Ali Sethi

1947 Archive, A global movement to collect and preserve witness accounts of Partition

Indian Summer by Alex von Tunzelmann

Indian Summers, a British TV drama series, various writers

Train to Pakistan by Khushwant Singh

Tamas, a movie by Govind Nihalani.

Partition map, courtesy of Themightyquill

Gandhi in Bela, Bihar, after attacks on Muslims, 28 March 1947, source unknown

Muslim refugees waiting to be transported to Pakistan, courtesy of Manchester Guardian, 27 September 1947

Filed under Society and Politics

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to An Unrestored Woman. It originally ran in April 2016 and has been updated for the

March 2017 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to An Unrestored Woman. It originally ran in April 2016 and has been updated for the

March 2017 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.