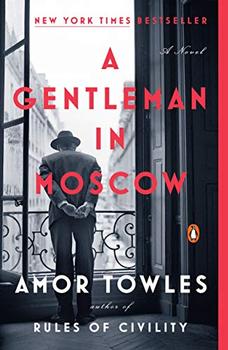

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to A Gentleman in Moscow

In A Gentleman in Moscow, Count Alexander Ilyich Rostov is sentenced to live the rest of his life within the walls of his current residence – Moscow's Hotel Metropol.

One of the oldest hotels in Russia, the Metropol was originally named the Chelyshy after its owner, Pyotr Chelyshev, who opened the facility as a bath house and three-story hotel in 1838.

Its modern history begins in 1898 when it was purchased by the St. Petersburg Insurance Association and rented out to the North Homebuilding Society headed by wealthy railroad entrepreneur Savva Mamontov. Mamontov had a vision for the property: he wanted to turn it into something much grander than the current hotel, wishing to create a cultural and leisure center that would be the envy of the world. To that end, a design competition was held in 1899, which was won by noted architect Lev Kekushev. Mamontov felt Kekushev's plans weren't innovative enough, however, and overruled the selection committee to give the contract to 28-year-old architect William Walcott (also spelled Walcot). It became one of the first structures in Moscow to be built in the Art Nouveau style.

The project was not without its drama. Mamontov was arrested for embezzlement soon after construction started and so others were left to fulfill his dream. The structure also burned to the ground in 1901, requiring building to start over from scratch. The Metropol finally opened its doors to visitors in March 1905. It immediately became a popular luxury hotel boasting amenities seldom seen in Russia; it was fully equipped with electricity, and all rooms, no two of which were alike, had hot water and telephones. In addition to its well-regarded restaurants and bars, the building housed Europe's largest theater, a skating rink, interior garden, an indoor stadium, and multiple exhibition halls. In 1906 the first two-auditorium cinema opened in the hotel.

The Metropol also had the advantage of location. It was built next to the medieval Kitai-Gorod Wall (the oldest part of Moscow and considered the heart of its historic district), across the street from the famous Bolshoi Theatre and near the Moscow Kremlin. As a result it became the place for the international elite to stay when traveling to Moscow, hosting wealthy foreigners as well as Russian aristocrats.

In November 1917, the hotel was taken over by the Bolsheviks during the Russian Revolution. It became the Second House of the Soviets, and instead of paying guests, its luxurious rooms were inhabited by highly placed Party officials. Various people's committees used its halls for their meetings, and some Party offices were also moved from the Kremlin to the Metropol. It remained exclusively for the use of the Soviet Republic until it reopened as a hotel in 1931.

The building went into decline until a five-year reconstruction project begun in 1986 restored the hotel to its former glory, once again allowing it to rank as one of the top hotels in the world. Room rates currently run from 14,000 – 18,000 rubles (about $425 - $2500) per night, depending on the type of room or suite.

In 2012, the Metropol was auctioned off by the city of Moscow as part of a privatization program. It was purchased by Alexander Klyachin, chief executive of Russia's Azimut Hotels, for 8.9 billion rubles (approximately $280 million).

Picture of The Metropol by NVO

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to A Gentleman in Moscow. It originally ran in September 2016 and has been updated for the

September 2016 edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to A Gentleman in Moscow. It originally ran in September 2016 and has been updated for the

September 2016 edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.