Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Stories

by Denis JohnsonThis article relates to The Largesse of the Sea Maiden

"Strangler Bob", one of the more memorable stories in The Largesse of the Sea Maiden, is set entirely within the squalid confines of an American prison. As far as we know, Johnson himself never spent any time in jail; the story is a testament to the power of imagination shorn of experience.

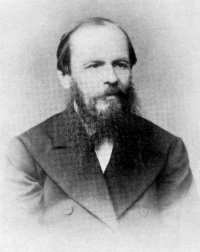

Throughout history though, there have been many great authors who, due to bad behavior or bad luck, haven't had to rely solely on their imaginations in order to describe prison life. Some of these figures, like Fyodor Dostoyevsky, Oscar Wilde, and Voltaire, were victims of backward social conditions or repressive regimes (what we would now call "prisoners of conscience"). Others, such as the Marquis de Sade, and his twentieth-century successor, William S. Burroughs, were genuine rascals and criminals (Sade was incarcerated for procuring young prostitutes, while Burroughs drunkenly shot and killed his wife).

Most of us are rightly ambivalent about the latter kind of literary inmate, but the former has a special place in world culture. Embodying as he or she does the heroism of the individual spirit, of the infallibly agile mind, this sort of writer heroically manages not to be crushed by the cruelty and repetition of incarceration, and instead transforms that cruelty into art.

Voltaire, whose satirical writings got him locked up in the Bastille for almost a year in 1717, continued to write, even from his cramped and dingy cell. In doing so, the French writer embodied a principle — that one can encage the body but not the mind — that has encouraged many, including the finest "prison writer" of them all, Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

As well as investing his life with a new intellectual acuity and fierce moral passion, Dostoyevsky's experience in a brutal Siberian work-camp (between 1849 and 1854) inspired him to write the autobiographical novel House of the Dead (sometimes rendered in English as Notes from a Dead House). The book, one of the founding texts in the sub-genre of prison literature, details the daily humiliations and drudgeries, the hunger and fear and boredom of this most unpleasant of environments, with supreme skill. And it has cast a long shadow over Russian literature. When, a century later, the Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — another long-suffering prisoner of conscience — published his powerful denunciations of the Gulag, it was Dostoevsky to whom he was favorably compared.

As well as investing his life with a new intellectual acuity and fierce moral passion, Dostoyevsky's experience in a brutal Siberian work-camp (between 1849 and 1854) inspired him to write the autobiographical novel House of the Dead (sometimes rendered in English as Notes from a Dead House). The book, one of the founding texts in the sub-genre of prison literature, details the daily humiliations and drudgeries, the hunger and fear and boredom of this most unpleasant of environments, with supreme skill. And it has cast a long shadow over Russian literature. When, a century later, the Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn — another long-suffering prisoner of conscience — published his powerful denunciations of the Gulag, it was Dostoevsky to whom he was favorably compared.

Perhaps the most famous literary inmate of them all was Oscar Wilde, who spent two grueling years in Reading Gaol in England, on charges of "gross indecency" (the conservative establishment's euphemism for homosexual behavior.) As with his Russian counterpart, Wilde's imprisonment toughened his poetry and prose, allowing him access to lives and conditions he had never previously considered. According to Dostoevsky's biographer, Joseph Frank, the writer's four years in Siberia, though unimaginably harsh, bequeathed to him a powerful stoicism he would otherwise have lacked. Wilde himself expressed a similar ambivalence in his great letter De Profundis, whose subject is the experience of prison. In notably un-Wildean terms, he resolves "to absorb into my nature all that has been done to me, to make it part of me, to accept it without complaint, fear or reluctance."

It is this tough, inspiring determination to accept, and persevere, and survive, whatever the odds, that characterizes the best of prison literature, and it is something that the above writers shared, however different they may have been in life. Each of them, in his own way, had his eyes — to borrow a line from Wilde's "The Ballad of Reading Gaol" — "Upon that little tent of blue / Which prisoners call the sky."

Filed under Books and Authors

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Largesse of the Sea Maiden. It originally ran in January 2018 and has been updated for the

January 2019 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Largesse of the Sea Maiden. It originally ran in January 2018 and has been updated for the

January 2019 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

When you are growing up there are two institutional places that affect you most powerfully: the church, which ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.