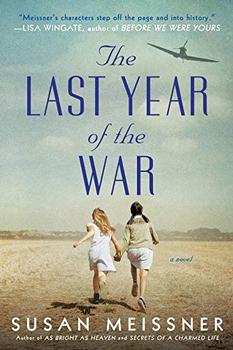

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to The Last Year of the War

In The Last Year of the War by Susan Meissner, the novel's main character is a child of German descent confined to the Crystal City internment camp during World War II, and later repatriated with her family to Germany. Many of us are aware of the exclusion, removal and detention of 120,000 people of Japanese heritage that occurred as the country entered WWII. Less familiar to most are the proceedings the government took against those of German and Italian birth.

In The Last Year of the War by Susan Meissner, the novel's main character is a child of German descent confined to the Crystal City internment camp during World War II, and later repatriated with her family to Germany. Many of us are aware of the exclusion, removal and detention of 120,000 people of Japanese heritage that occurred as the country entered WWII. Less familiar to most are the proceedings the government took against those of German and Italian birth.

The groundwork for action against foreign-born individuals actually began in the mid-1930s, as part of J. Edgar Hoover's campaigns against communism and Nazism. Under his direction, the FBI developed a list of individuals, referred to as the Custodial Detention Index or the ABC List, ranking people on the basis of their perceived risk, taking into account things like membership in suspect groups, magazine and newspaper subscriptions, overseas visits and tips from anonymous informants. By 1939, the FBI claimed they were monitoring more than 10 million people that they considered threats to American security or values.

This paranoia was not restricted to the FBI; by June 1939, Congress was discussing the establishment of concentration camps for those they considered political extremists, and several anti-alien and anti-sedition laws were passed at the state level. Most legislation relied on the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 as a basis, which gives the president the power to apprehend, restrain and remove resident enemy aliens during times of war or national emergency. (Although amended over the years, the 1798 law remains on the books; both George W. Bush and Barack Obama used this same act to imprison those suspected of terrorism.) In 1940, the United States passed the Alien Registration Act, requiring the registration and fingerprinting of all resident aliens (about 4.9 million people).

The round-up of people of German and Italian birth living in the United States began December 8, 1941, three days before the United States declared war on the Axis powers. These individuals (many of whom were naturalized US citizens) were subjected to an Alien Enemy Hearing Board, held in each judicial district across the country. The board was comprised of three civilian members, one of whom was an attorney, plus representatives of the local district attorney's office, the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service) and the FBI; the person being investigated was permitted no legal counsel. They could expect one of three verdicts: release, parole or incarceration for the duration of the war. Ultimately, nearly 15,000 German and Italian individuals were confined in the United States throughout WWII. (Some proposed restrictions on all those of German heritage, but that was considered untenable; there were 1.2 million people of German birth in the US by 1940.) Generally, just males were restricted, but frequently the rest of the family would voluntarily accompany the accused, as the incarceration of the head of the household usually left the family without a means of support.

The US government's concern about the loyalties of those of Japanese, German or Italian birth wasn't limited to people living in the country; Hoover's list extended to those in Latin American nations as well. At the FBI's insistence, some 3,000 people from Central America, South America and Caribbean countries were stripped of their citizenship, declared illegal aliens and deported to one of 20 US detention centers

There's speculation that in addition to simply being concerned about the country's safety, another goal of incarcerating German, Italian and Japanese citizens was to create a pool of people that could be swapped for American POWs, and indeed thousands were returned to their country of origin (taking their American-born children with them). The United States used these individuals to barter for the release first of government employees and diplomats, and later severely wounded US soldiers and other citizens. Four large-scale exchange operations took place involving Crystal City inhabitants: approximately 2,000 Japanese were "repatriated" in June 1942 and September 1943, 634 Germans and their children were exchanged in February 1944, and another 428 Germans were traded in February 1945.

by Kim Kovacs

Crystal City Internment Camp, courtesy of Texas Historical Commission

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Last Year of the War. It originally ran in March 2019 and has been updated for the

April 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Last Year of the War. It originally ran in March 2019 and has been updated for the

April 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.