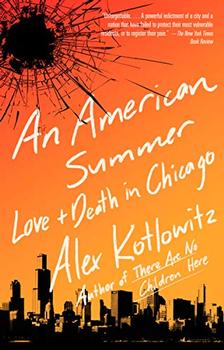

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Love and Death in Chicago

by Alex KotlowitzThis article relates to An American Summer

When people talk about Chicago, the endemic violence inevitably comes up, along with a sense of helplessness about how to stop it. That helplessness leads to apathy, and the feeling that the neighborhoods torn apart by gun violence are forsaken, failed places. But this attitude is as much a cause as it is an effect of crime and violence. In her memoir Becoming, Michelle Obama articulated the connotations of failure with Black neighborhoods: "There were predatory real estate agents roaming South Shore all the while, whispering to home owners that they should sell before it was too late, that they'd help them get out while you still can. The inference being that failure was coming, that it was inevitable, that it has already half arrived. You could get caught up in in the ruin or you could escape it."

When people talk about Chicago, the endemic violence inevitably comes up, along with a sense of helplessness about how to stop it. That helplessness leads to apathy, and the feeling that the neighborhoods torn apart by gun violence are forsaken, failed places. But this attitude is as much a cause as it is an effect of crime and violence. In her memoir Becoming, Michelle Obama articulated the connotations of failure with Black neighborhoods: "There were predatory real estate agents roaming South Shore all the while, whispering to home owners that they should sell before it was too late, that they'd help them get out while you still can. The inference being that failure was coming, that it was inevitable, that it has already half arrived. You could get caught up in in the ruin or you could escape it."

The notion that certain areas are "failures" absolves those in a position of power from having to face the consequences of deliberate policy decisions. Nowhere is this more obvious in the recent history of Chicago than the wave of school closings announced in 2013 by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, which resulted in the closure of 50 schools deemed "underutilized" and "failing" by authorities.

Parents, teachers and students alike rejected the reasons for the closures, namely that with falling enrollment, these schools were failing and should be shuttered so that students could go to better schools. And there was an unmistakable current running through the proposition: as Eve Ewing shows in Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago's South Side, 90% of the schools slated to be closed were majority Black, and 88% of all students affected by the closures city-wide were Black. It was a stunning blow to neighborhoods grappling with poverty and violence.

When public hearings were held, the explanation given by Chicago Public Schools (CPS) officials did little to clarify why these schools were so problematic. Ewing documents how the under-utilization figures were based on numbers and percentages with no context. In their presentation to parents, CPS staff declared these schools' "enrollment efficiency range" were below the "ideal enrollment" numbers, hence they should be closed. But the numbers were arbitrary: ideal enrollment was described as a school having homerooms with 30 students, and CPS said the "allotted" number of homerooms were set at 76-77% of total classrooms.

None of the figures were explained, i.e., why 30 is the ideal number of homeroom students, or how 76-77% of classrooms should be allotted as homerooms. The logic implied, as Ewing explains, "…the idea that the most important aspects of the educational enterprise can easily be captured in no-nonsense, non-debatable numeric facts."

While those figures went unexplained, there were numbers that all parties agreed upon—enrollment numbers were falling at schools across the South and West sides. What wasn't addressed was twofold: first, if lower enrollment was detrimental to students, who would arguably stand to benefit from lower teacher-to-student ratios, and second, how falling enrollment was related to the city's Plan for Transformation.

The Plan for Transformation, released in 1999, demolished public housing projects across the South and West sides of Chicago, which had become epicenters of poverty and violence. The city claimed it would provide vouchers for affordable housing in re-developed homes where the projects once stood. Yet the Chicago Sun-Times reported in 2017 that upwards of 17,000 apartments still hadn't been rebuilt. Consequently, the population of these areas, including school-age children, has plummeted.

The housing projects were indeed unhealthy and in need of reform, but they took shape as they did, Ewing reveals, because high-rises with small apartments were cheaper to build than row houses, and because of ongoing segregation in Chicago neighborhoods. Thus, their demolition and the resulting population loss was the outcome of racially discriminatory policies, and the effects were used to justify further deprivations to Black communities in the form of school closures.

Officials offered the reasoning that children would have a better future at different, and by extension, better schools. The results have not proven this, however, and a recent study by the University of Chicago shows that students from closed schools as well as those attending "welcoming" schools (schools that absorbed students from those that were closed) had negative trends in test scores, both short- and long-term. According to the 2018 results, "The evidence provided in this report suggests that closing schools and moving students…did not automatically expose them to better learning environments and result in greater academic gains."

Student safety and transportation issues were noted in the University of Chicago study as further problems with shuttering 50 schools. And while city and CPS officials vigorously denied any racial motivation, when viewed in the historical context of the city, they were "the culmination of several generations of racist policy stacked on racist policy, each one disregarding, controlling, and displacing Black children and families in new ways layered upon the callousness of the last," according to Ewing. These closures perpetuate the very problem of under-resourced education they claimed to be solving.

Protest of school closings, courtesy of CNN

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This article relates to An American Summer.

It first ran in the April 17, 2019

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to An American Summer.

It first ran in the April 17, 2019

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.