Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to The Island of Sea Women

Lisa See's novel, The Island of Sea Women, highlights the lives of haenyeos – women from the South Korean island of Jeju who support their families by free-diving for plants and animals that thrive in the ocean. They're known to be able to hold their breath for two to three minutes at a stretch and can descend to depths of 30 to 45 feet below sea level.

Lisa See's novel, The Island of Sea Women, highlights the lives of haenyeos – women from the South Korean island of Jeju who support their families by free-diving for plants and animals that thrive in the ocean. They're known to be able to hold their breath for two to three minutes at a stretch and can descend to depths of 30 to 45 feet below sea level.

The women refer to the actual act of diving as muljil, and it is an art learned by each woman from childhood. It is a dangerous profession that requires an innate understanding of water pressure, tidal differences, sea temperature, and other hazards that could impact whether or not they have enough oxygen to return to the surface. Harvesting sea products in a sustainable manner has always been a priority for the haenyeos – for example, they avoid fishing during spawning periods so they won't disrupt the fish's lifecycle.

The divers rely on specialized equipment that they developed over the centuries. (The tradition dates back to around 400 CE.) Until the invention of the rubberized wet suit, each woman would dress in a loose cotton swimsuit known as a mulot, comprised of pants (mulsojungi), jacket (muljeokam), and a hair wrap (mulsugun). The garments opened on the side and were secured with ties, making them easy to put on and adjust as the women's body size changed over the years. (For example, as she became pregnant and subsequently gave birth.) They originally wore belts loaded with rocks to help them remain submerged, but more recently they've switched to using lead weights for this purpose.

The divers rely on specialized equipment that they developed over the centuries. (The tradition dates back to around 400 CE.) Until the invention of the rubberized wet suit, each woman would dress in a loose cotton swimsuit known as a mulot, comprised of pants (mulsojungi), jacket (muljeokam), and a hair wrap (mulsugun). The garments opened on the side and were secured with ties, making them easy to put on and adjust as the women's body size changed over the years. (For example, as she became pregnant and subsequently gave birth.) They originally wore belts loaded with rocks to help them remain submerged, but more recently they've switched to using lead weights for this purpose.

Another essential item is the tewak (or te-wak), a basketball-sized buoy that's left on the surface to indicate where a haenyeo is diving. A net, known as a mangsari, floats beneath the tewak and is used to store each woman's harvest throughout the dive, which can last up to six hours with the use of a wetsuit. They use prying tools called bitchang to harvest stubborn shellfish like abalone from cervices and a homaengie, a sickle-like instrument, for collecting grasses like seaweed. Along with those two items, they bring octopus, conch, sea mustard, sea cucumber, and sea urchin to market.

The South Korean government has recognized the haenyeo as a national treasure, subsidizing their gear and providing them medical coverage, as well as granting them exclusive rights to sell fresh seafood in Jeju to encourage the practice. Nevertheless, it's a dying art. There were over 26,000 haenyeo in the 1960s, but less than 4500 today, and as of 2014, 98% were over 50 years old.

The South Korean government has recognized the haenyeo as a national treasure, subsidizing their gear and providing them medical coverage, as well as granting them exclusive rights to sell fresh seafood in Jeju to encourage the practice. Nevertheless, it's a dying art. There were over 26,000 haenyeo in the 1960s, but less than 4500 today, and as of 2014, 98% were over 50 years old.

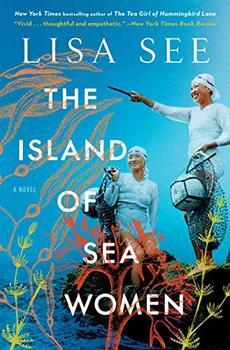

Haenyeos after diving for seaweed and octopus, courtesy of blog.bnbhero.com

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Island of Sea Women. It originally ran in May 2019 and has been updated for the

March 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Island of Sea Women. It originally ran in May 2019 and has been updated for the

March 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Great political questions stir the deepest nature of one-half the nation, but they pass far above and over the ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.