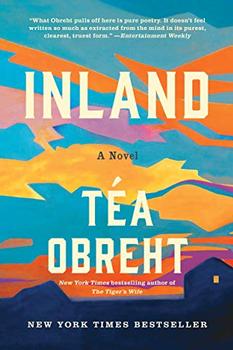

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Inland

A key section of Téa Obreht's novel Inland takes place among the Camel Corps, a real-life mid-19th-century experiment conducted by the United States Army attempting to introduce camels as beasts of burden in the Southwestern territories.

A key section of Téa Obreht's novel Inland takes place among the Camel Corps, a real-life mid-19th-century experiment conducted by the United States Army attempting to introduce camels as beasts of burden in the Southwestern territories.

This seemingly madcap idea originated when the army found they needed to vastly improve transportation in the arid, barren Southwest. The inhospitable terrain was not dissimilar to the great deserts of Egypt, and several high officials recommended that the War Department introduce camels to the army due to their strength, endurance and capacity to travel great lengths with minimal need for food, water and rest. In 1848, Mexican-American War veteran Major Henry C. Wayne put forward an official proposal that caught the attention of Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi. But it wasn't until Davis was appointed Secretary of War in 1853 that Wayne's Camel Corps plan was put into action.

Now that he had an official go-ahead, Major Wayne conducted a detailed study, and with help from U.S. Navy admiral Lieutenant David Dixon Porter, he set about procuring the animals. The two set sail from New York City to the Mediterranean Sea on board the USS Supply on June 4, 1855. They traveled through Tunisia, Malta, Greece, Turkey and Egypt, acquiring 33 camels of differing species. These included typical Arabian Dromedaries as well as the shaggier Central Asian Bactrian variety. Wayne and Porter also had the foresight to purchase the necessary camel-riding paraphernalia, such as appropriate pack saddles, knowing these wouldn't be available back home.

After almost a year of travelling around the Mediterranean, the army men together with their caravan set sail for home. They lost one male camel on the return voyage, but gained two calves. After another expedition to Egypt, the US Army was in possession of 70 camels, all of which were based in Campe Verde, Texas.

Several field experiments were set up to test the military usefulness of the camels. One such test was to send three mule-pulled wagons and six camels on a round-trip race for oat supplies in San Antonio. The mule drawn wagons carried 1,800 pounds of oats and took five days to make the journey. The camels, on the other hand, carried 3,648 pounds of oats and returned in two days. A clear win for the camels' strength and speed.

While the camels continued to prove their worth, carrying impossibly heavy loads across the rivers and mountains of the Southwest, the beginning of the Civil War effectively put a stop to the Camel Corps. Rebel troops attacked Campe Verde in 1861 and captured several of the animals. It appears the captors intensely disliked these foreign beasts. They cruelly mistreated and, in some instances, deliberately killed them.

Over the next three years, the remaining army camels were kept well, but the military made little use of them. Eventually the expense of their upkeep became unfeasible and they were sold at public auction. Despite their many successful expeditions made while in the army's employ, the camels' merits were still a mystery to most. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton commented before the auction: "I cannot ascertain that these have ever been so employed as to be of any advantage to the Military Service, and I do not think that it will be practical to make them useful."

Many of the camels were sold to local circuses where they were used for racing and as children's rides. Others ended up working on private ranches, making them a familiar if peculiar sight all the way from California to British Columbia. In time however, their novelty wore off and many were left to fend for themselves in the plains of the Southwest. In April of 1934, Topsy, the last of the original Camel Corps camels, died at the age of 80 (nearly double the normal lifespan of a camel, incidentally), and with him, the Army's camel experiment became a curious side note in the annals of U.S. military history.

Camels in Texas by Thomas Lovell, courtesy of The National Museum of the United States Army

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Inland. It originally ran in August 2019 and has been updated for the

May 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Inland. It originally ran in August 2019 and has been updated for the

May 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.