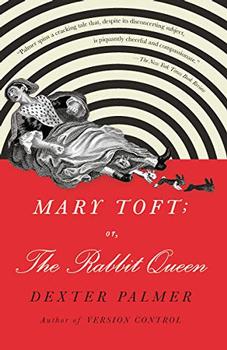

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen

A taste for blood and an unfortunate willingness to exploit those considered "Other" are not wholly unique to the Georgian period, but their prevalence during the era cannot be ignored. By 1726, when the subject of Dexter Palmer's novel Mary Toft; or, the Rabbit Queen, claimed to have given birth to a rabbit, the concept of difference as a means of entertainment had been long established. To understand why her particular case was given so much credence, we must examine the wider social landscape that underpinned life at the time.

A taste for blood and an unfortunate willingness to exploit those considered "Other" are not wholly unique to the Georgian period, but their prevalence during the era cannot be ignored. By 1726, when the subject of Dexter Palmer's novel Mary Toft; or, the Rabbit Queen, claimed to have given birth to a rabbit, the concept of difference as a means of entertainment had been long established. To understand why her particular case was given so much credence, we must examine the wider social landscape that underpinned life at the time.

There was big money to be made from the spectacle of physical difference. With traveling sideshows and human curiosities regularly drawing huge crowds, people with deformities, disabilities and rare medical conditions became the unexpected stars of the day. In today's world, the exploitation and cruelty involved in parading vulnerable people before a horrified audience are clear, but for the contemporaries of Mary Toft, this was commonplace.

Given the Georgians' fascination with physical difference, it likely comes as no surprise that those with mental health struggles were also considered fair game within the sphere of entertainment. London's psychiatric hospital for the insane – now commonly known as Bedlam – had people queuing up to get in for a day visit. This was not to comfort loved ones or to offer their services, but to observe the patients with a misguided blend of fear and excitement. For some, a jaunt in the capital simply wasn't complete unless they'd taken in the scandalous sights behind Bedlam's walls.

For better or worse, the Georgians' penchant for the "exotic" was not reserved for humans alone; animals from across the globe were also subject to public scrutiny. Wealthy and well-traveled men would source everything from lions to monkeys, certain of the huge earning potential that lay in such a collection. A famous example was the Tower of London Menagerie, which grew from its inception in 1235 to become an essential Georgian tourist destination. (The London Zoo in Regents Park was founded to house the animals from the menagerie after it closed in 1835.) Sometimes the novelty of seeing an elephant or a leopard in an urban setting was enough to delight onlookers. In other cases, the animals would be forced to perform tricks to pull in extra cash. This included everything from birds that could obey commands, to Toby the Sapient Pig, who traveled the country throughout the 1820s, delighting onlookers with his supposed talent for mind-reading.

Perhaps even more upsetting to consider by today's standards is the popularity of blood sports at the time. From cockfighting and badger-baiting, to bull running and bear hunting; certain circles of Georgian society were not content with simply taking in the aesthetic majesty of animals. They demanded bloodshed, and bloodshed is precisely what they got.

But if these painfully outdated forms of entertainment emerged before Mary Toft's day, and lingered long after, why did they all seemingly peak in popularity during the Georgian period? The different sensibilities of the time are an obvious factor, but there's more to it than that. The rise of cities and significant improvements to travel routes meant that many country dwellers were venturing into urban environments for the first time. Those from sheltered upbringings in sparsely populated rural areas were unlikely to have been exposed to different ethnicities before, let alone disability and deformity. Finding themselves confronted by such an array of physical and cultural differences likely inspired a sense of awe and puzzlement that manifested in morbid curiosity and a need to exert control.

It's also worth considering the impact of the Enlightenment, which was in full swing during Mary's lifetime. Society was becoming less insular, and the scientific breakthroughs of the day often clashed with the long-held culture of religion and old wives' tales. The newfound thirst for knowledge, and the eagerness to categorize the world around them is perhaps what drew so many towards such tasteless forms of entertainment. The notoriety that came with finding new ways to understand the perplexities of life could also explain why even the greatest thinkers of the day were so willing to believe the wild claims of one young woman fit for a sideshow – a woman who claimed to have given birth to multiple rabbits.

Satirical cartoon called "The anti-royal menagerie" by William Henry Brooke, 1812, courtesy of The British Museum

Filed under Cultural Curiosities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen. It originally ran in January 2020 and has been updated for the

October 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Mary Toft; or, The Rabbit Queen. It originally ran in January 2020 and has been updated for the

October 2020 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.