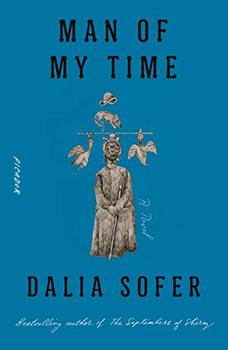

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Man of My Time

Dalia Sofer's novel Man of My Time spans from the mid-20th century to the present day. Set in both Tehran and New York City, it encompasses the decades leading up to the 1979 Iranian Revolution—when Iranians from both Islamist and leftist organizations overthrew the Western-backed Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi—as well as the revolution itself, its aftermath and the modern geo-political situation between the U.S. and Iran. While reading, I found myself wondering about the Shah's regime in Iran before the rise of theocratic government.

Dalia Sofer's novel Man of My Time spans from the mid-20th century to the present day. Set in both Tehran and New York City, it encompasses the decades leading up to the 1979 Iranian Revolution—when Iranians from both Islamist and leftist organizations overthrew the Western-backed Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi—as well as the revolution itself, its aftermath and the modern geo-political situation between the U.S. and Iran. While reading, I found myself wondering about the Shah's regime in Iran before the rise of theocratic government.

Mohammad Reza was educated in Switzerland as a teenager and became Shah during World War II when the Allies deposed his father, Reza Shah Pahlavi, who had connections with Germany and had disrupted supply lines between the British and the Soviets that ran through Iran. 22-year-old Mohammad Reza came to power in 1941 and entered into an agreement with the Allies that kept the supply lines open and guaranteed the preservation of Iran's independence.

There is usually more than one side to a person, and the Shah was no exception. Purportedly a generous, shy man in private, he wore a mask projecting authority and aloofness in public. He considered himself to be like a father to the Iranian people and believed that as long as he governed as a good father the people would remain loyal to him. However, he stepped back from his position of authority twice during his rule due to unrest (first in 1953 during a conflict with Prime Minister Mossadeq, and then in 1963 during religious protests led by the cleric Ayatollah Khomeini). The Shah could not bring himself to move against his people by ordering the military to crack down on dissent, so he left this job to others in the government, such as his close adviser and minister Asadollah Alam.

Although the Shah continued his father's efforts to modernize the country by building roads, schools and factories, investing huge sums of money in the military, initiating land reforms and supporting women's rights, he was by no means a progressive ruler. His was an authoritarian monarchy that concentrated wealth and power within his family, the well-funded military and the petro-bourgeoisie (courtiers who profited from oil revenues). This concentration of wealth alienated the poor and certain left-leaning groups, while his championing of women's rights and other reforms that were perceived as Westernizing angered Islamic traditionalists.

Corruption was rife among the elite and the gulf between the wealthy and the poor grew ever wider. Members of the upper echelon thought nothing of flying to Europe for an elegant lunch and then back to Tehran for dinner. In the meantime, Tehran lacked a modern sewage system. In a land rich with oil, citizens dealt with shortages of cooking oil and other essentials, and people in the countryside burned cow dung for heat.

The divide between the rich and poor, the corruption and abuse of power, and a sluggish economy in the latter half of the 1970s all fueled resentment toward the Shah and his government. However, open dissent was unthinkable. Savak, the notorious secret police trained by members of the American and Israeli intelligence agencies, prowled the country, picking up citizens for uttering simple words (like "oppressive," "darkness" or "burden") thought to be coded negative commentary about the Shah. Citizens detained by Savak were subject to imprisonment, torture and execution.

A bifurcated power structure, with authority being somewhat balanced between the monarchy and the mosque, complicated the socio-political situation. The Iranian clerics were often critical of the Shah's policies and the open courtyards of mosques were places where citizens could gather in order to discuss topics they feared to speak of elsewhere. Though mosques afforded the populace a modicum of free speech, Savak still persecuted clerics who spoke out against the Shah.

In January 1978, an Iranian newspaper published an article that was critical of Ayatollah Khomeini, claiming he was a British agent working against national interests championed by the Shah, such as land reform and women's rights. People in Qom, a religious center, gathered to discuss the article, and several were killed by the military. This event set off protests throughout 1978, which were also met with brutal force. These protests were not only in support of Khomeini, but also in opposition to the brutality of the police and Savak against the Iranian people. According to Polish journalist Ryszard Kapuściński, "[t]he Shah left people a choice between Savak and the mullahs. And they chose the mullahs."

By the end of January 1979, the Shah and his family had left Iran for the last time. On April 1st, 1979 the monarchy was officially abolished. The Islamic Republic of Iran was declared, and Khomeini would become Supreme Leader, the highest political and religious authority in the country.

Mohammad Reza Shah circa 1949

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Man of My Time. It originally ran in April 2020 and has been updated for the

April 2021 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Man of My Time. It originally ran in April 2020 and has been updated for the

April 2021 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

You can lead a man to Congress, but you can't make him think.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.