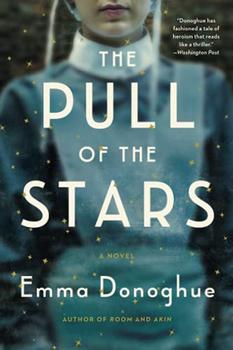

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to The Pull of the Stars

Often referred to as the Spanish Flu, the 1918 flu pandemic is one of the deadliest viral outbreaks the world has ever seen. Hitting its peak at the tail-end of World War I, record-keeping was poor by modern standards, but it is estimated that some 500 million people (about a quarter of the world's population at the time) became infected across its three waves, with around 50 million of them succumbing to the illness.

Often referred to as the Spanish Flu, the 1918 flu pandemic is one of the deadliest viral outbreaks the world has ever seen. Hitting its peak at the tail-end of World War I, record-keeping was poor by modern standards, but it is estimated that some 500 million people (about a quarter of the world's population at the time) became infected across its three waves, with around 50 million of them succumbing to the illness.

Though its common moniker suggests the outbreak originated in Spain, this is in fact untrue. With much of Europe embroiled in the ongoing conflict of WWI, many countries were subject to strict news censoring and media blackouts by the time the virus emerged. Not wishing to further damage morale among citizens already living in fear, or to show perceived weakness in front of their enemies, most countries chose to suppress news of the virus. Spain, being neutral, was free to report openly, and with many people thus hearing of the pandemic from Spanish sources, the name "Spanish flu" was born.

In reality, the exact origins of the outbreak are unknown. Though the European mainland is generally seen as the epicenter of the disaster, the U.S. was also hit hard, with at least 675,000 deaths. In fact, one of the first reported cases of the virus was at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas in March 1918. Given that the pandemic spread rapidly across America and Europe at the same time, many now believe it might actually be traced back to the U.S. originally, with troops spreading the virus as they traveled to and from Europe as part of the war effort.

Indeed, there is no doubt the war helped to fuel the speed and severity of the virus' spread. Hospitals were already dangerously overstretched and understaffed; hygiene and cleanliness were far from priorities; many people were malnourished and in poor health as a result of rationing; cramped, boggy trenches provided ideal conditions for the virus to thrive; and soldiers and nurses were beginning to return from the frontline, almost certainly bringing the virus back to their home nations with them.

During the first wave, symptoms were typical of the regular flu and the death rate remained fairly low, with victims complaining of fever and fatigue. It was the highly contagious second wave that proved particularly devastating, however. As the illness targeted the immune system, people turned visibly blue as their lungs filled with their own bodily fluids, causing them to suffocate from the inside. So intense was this bout of the virus, many were dead within a few hours of first feeling unwell.

Societal and governmental responses to the outbreak were not unlike those seen with the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Businesses, schools and public spaces were forced to close, communities were put under quarantine, gatherings were to be avoided, and medical students were fast-tracked through their studies so they could help make up the shortfall in required health care. As in 2020, citizens were also widely encouraged (and in some cases required) to wear masks to help slow the spread of virus particles. Though most willingly complied, fines were issued to those who failed to do so, with several local authorities and newspapers even running public campaigns to name and shame so-called "mask slackers."

The worst of the pandemic was over by the end of 1919. This may seem like a relatively brief time, but that is precisely why it proved so deadly. With so many people becoming infected at once, health care services were quickly overwhelmed and the illness spread like wildfire. In a matter of months, tens of millions were dead, with many bodies simply discarded in makeshift mass graves.

Although the pandemic itself ended, the virus that caused it did not go away. It was still circulating in the 1920s but was much less lethal, probably due to a combination of herd immunity and the virus naturally weakening (from an evolutionary perspective viruses are able to spread most widely when they do not kill their host, so they tend to evolve into milder forms over time). According to a 2009 article co-authored by the current NIAID director Anthony S. Fauci, "the descendants of the H1NI virus that caused the 1918 pandemic have continued to contribute their genes to new viruses, causing new pandemics, epidemics, and epizootics." In fact, all the pandemics that have occurred since 1918 (including 1957, 1968 and 2009) are derivatives of the 1918 flu; the echoes of its devastating impact still being felt to this day.

Camp Funston circa 1918, courtesy of National Museum of Health and Medicine

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Pull of the Stars. It originally ran in August 2020 and has been updated for the

July 2021 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Pull of the Stars. It originally ran in August 2020 and has been updated for the

July 2021 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Discovery consists of seeing what everybody has seen and thinking what nobody has thought.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.