Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Sarah PennerThis article relates to The Lost Apothecary

In Sarah Penner's The Lost Apothecary, a historical mystery is set in motion when a character discovers a small blue vial while mudlarking. "Mudlarking" refers to the practice of scavenging for objects — generally manufactured or otherwise manmade ones that have been lost or thrown away — usually on the shore of a body of water such as a river. While one can mudlark anywhere in the world given the right conditions, the term originally described picking up items of value along the muddy banks of the River Thames in London, where Penner's novel takes place, and still has strong ties to the area.

In Sarah Penner's The Lost Apothecary, a historical mystery is set in motion when a character discovers a small blue vial while mudlarking. "Mudlarking" refers to the practice of scavenging for objects — generally manufactured or otherwise manmade ones that have been lost or thrown away — usually on the shore of a body of water such as a river. While one can mudlark anywhere in the world given the right conditions, the term originally described picking up items of value along the muddy banks of the River Thames in London, where Penner's novel takes place, and still has strong ties to the area.

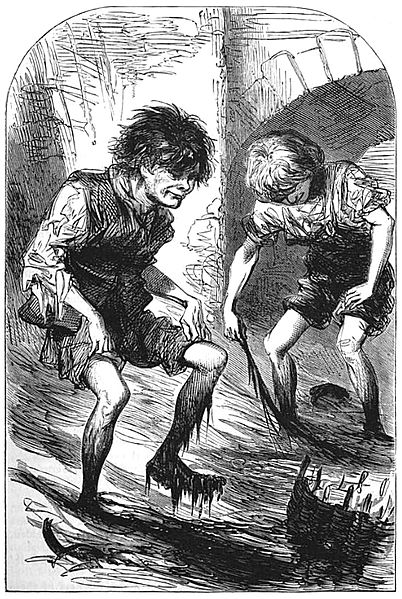

Lara Maiklem, author of Mudlarking, first began scavenging on her family's farmland and has been scouring the shore of the Thames for objects of interest for upwards of 15 years. In an interview with Collectors Weekly, Maiklem explains that the word "mudlark" emerged in association with the river around the late 1700s, when gangs stole from cargo ships anchored on it. Alongside these groups, less ambitious criminals attempted to help themselves to crumbs of the illicit enterprises. These "pathetic wretches," who snatched up stray goods that the gangs dropped or left behind, such as sugar and spices, and attempted to sell them for a profit, were referred to as "mudlarks." Many of them were poor women and children attempting to survive in a society that did not offer them other viable options. They became better known to the general public later on, around the mid-1800s, when writers such as Henry Mayhew began to investigate their impoverished existence and describe it as a cultural phenomenon.

In current times, "mudlarking" also describes the activities of those like Maiklem who flock to the Thames with shovels and metal detectors in hand. Rather than searching for discarded goods to sell on the black market, the London mudlarks of today tend to be excited by the rich history of the area and the possibility of fascinating discoveries along the foreshore during low tide. In addition to the river's status as part of a major trade route that drew the original mudlarks, it has also always been a central fixture of London as a whole, and human presence in the area far predates the city itself. Because of this, it isn't unusual for objects from Victorian, Georgian or even earlier times to turn up. Maiklem's finds over the years include Roman pottery, a syringe likely used to treat syphilis around the 18th century, flint shaped during the Mesolithic era, a glass eye, and many more objects of historical and cultural significance.

You need a permit to mudlark along the Thames these days, at least if you plan on digging or even turning over rocks, and there are certain restrictions placed on what you can do with what you pick up; for example, you are prohibited from selling any of the items, which all legally belong to the Port of London Authority. Maiklem indicates that it is important to take safety precautions and be mindful of the tides. She also points out that good scavenging prospects exist far beyond the banks of the Thames, or in fact any river, commenting on the possibilities of "garden-larking and field-larking and beach-larking."

While Maiklem has put ample time and enthusiasm into acquiring her collection of found objects, beginners' efforts, too, can yield significant discoveries. In an article for Frommer's, Jason Cochran lays out some basics of mudlarking on the Thames, including how to circumvent actions that require a permit and examples of what you might come across. First-time mudlarks may not typically find a clue that leads to an investigation of mysterious events from days past, but shards of Tudor beer vessels as well as centuries-old clay pipes, which beginning in the 1500s were "tossed ... into the water the way modern people flick cigarette butts," are abundant, and even more intriguing finds are always possible.

"Mudlarks of Victorian London in the River Thames" from The Headington Magazine in 1871, via Wikimedia Commons

Filed under Cultural Curiosities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Lost Apothecary. It originally ran in March 2021 and has been updated for the

February 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Lost Apothecary. It originally ran in March 2021 and has been updated for the

February 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

To be ignorant of what occurred before you were born is to remain always a child

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.