Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Deathless #1

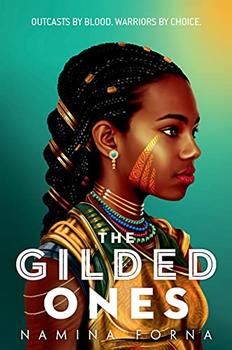

by Namina FornaThis article relates to The Gilded Ones

In a letter addressed to readers in The Gilded Ones, Namina Forna writes that the book is "at its heart…an examination of patriarchy. How does it form? What supports it? How do women survive under it? And what about people who don't fall into the binary? Who thrives and who doesn't?" Deka and all the women of Otera live in a society that considers them second-class citizens, and the women designated "alaki" are further stigmatized as impure monsters. Of course, as the narrative reveals, it is the power of these women, the potential of what they can become, that is feared.

In a letter addressed to readers in The Gilded Ones, Namina Forna writes that the book is "at its heart…an examination of patriarchy. How does it form? What supports it? How do women survive under it? And what about people who don't fall into the binary? Who thrives and who doesn't?" Deka and all the women of Otera live in a society that considers them second-class citizens, and the women designated "alaki" are further stigmatized as impure monsters. Of course, as the narrative reveals, it is the power of these women, the potential of what they can become, that is feared.

This fear is a frequent theme in literature and media, often realized through the trope of the monstrous woman as a means of demonizing female power. Monstrous women disturb the ideal of the woman as innocent and pure, as the mother and angel of the home. From classical works such as Euripedes' Medea tragedy to contemporary books like Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale and Angela Carter's fairy tale adaptations, women who do not conform to the demands of patriarchy, or otherwise subvert and bend it to their will, are made out to be monstrous. But as Forna demonstrates in her novel, these characters can also serve as a commentary on what is truly repugnant or monstrous within a society.

There are myriad examples of monstrous depictions of women in literature, mythology and popular culture — from Grendel's mother in Beowulf to DC comics' Harley Quinn — and a great deal of scholarship on what these characters represent. The female monster is often a figure used to criticize the structures of patriarchy. In a 1999 essay in the Journal of Gender Studies, Sara Martin describes characters in the work of authors Fay Weldon, Angela Carter and Jeannette Winterson as "monstrous women who enjoy power over men." These characters represent a version of the monstrous woman who is "triumphant" in claiming power for herself in a patriarchal society. In a piece for the philosophical journal PhaenEx, Dianna Taylor writes that "monstrous women challenge limits — including prevailing norms governing the feminine and the human — in ways that render them explicit such that they are denaturalized and ultimately opened up to critical interrogation." What Taylor is noticing is that a so-called "monstrous woman" may not be a monster at all, but a comment on the patriarchal system that makes her actions aberrant. In other words, a woman becomes monstrous by merely acting outside of patriarchal norms. In The Gilded Ones, the alaki are not monsters at all, despite the society of Otera labeling them as such. In a 2019 essay in Granta, Hannah Williams notes: "Despite the sheer and uncommunicable amount of violence enacted upon the female body throughout history, it's woman as terroriser, as beast, that we keep coming back to." When a woman becomes a monster — say, a witch with snakes for hair like Medusa, or even a run-of-the-mill murderer — it is strange to us in a way that reinforces the patriarchal norm of men enacting violence on women.

These three instances alone demonstrate 30 years of writers thinking about how monstrous women in media embody the fear of disruption of the patriarchal system, and how these depictions represent women seizing power. These are women who cannot be controlled, who can dismantle power structures, who claim their agency and equality. In books like The Gilded Ones, the so-called monsters are those who have power to break through the patriarchal system. The alaki are sentenced to death because of the threat they represent to the Emperor's order. By deliberately writing heroines like these, women are given space to be monstrous, and to move beyond the patriarchal roles they have been forced into.

Medusa by Arnold Böcklin, circa 1878

Filed under Books and Authors

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Gilded Ones. It originally ran in May 2021 and has been updated for the

January 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Gilded Ones. It originally ran in May 2021 and has been updated for the

January 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.