Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

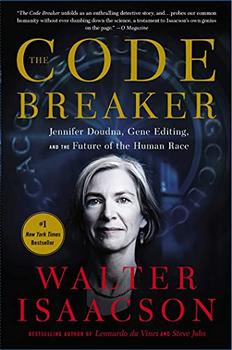

Jennifer Doudna, Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race

by Walter IsaacsonThis article relates to The Code Breaker

When a scientific breakthrough is achieved, it can be a moment of major celebration. Depending on the implications of that advancement, previously unknown individuals can find themselves vaulted into the highest levels of celebrity. Yet, the challenge of deciding who is truly responsible for the scientific advancement can be contentious. Very rarely does one person make a discovery in a vacuum, as other researchers are often working the same problem set. This is seen throughout scientific history and in recent times.

When a scientific breakthrough is achieved, it can be a moment of major celebration. Depending on the implications of that advancement, previously unknown individuals can find themselves vaulted into the highest levels of celebrity. Yet, the challenge of deciding who is truly responsible for the scientific advancement can be contentious. Very rarely does one person make a discovery in a vacuum, as other researchers are often working the same problem set. This is seen throughout scientific history and in recent times.

In The Code Breaker, Walter Isaacson explains how the potential for using CRISPR and CaS9 to edit DNA was a significant advancement in gene editing with implications for the future of medicine and humanity. However, no sooner had Dr. Jennifer Doudna and her team put out the first article documenting their discoveries when another team of scientists, led by biochemist Feng Zhang, who had also been working on CRISPR-based gene editing, published their own article on the subject. What followed was a years-long battle in international court (and the court of public opinion) to determine who would get the patent, and the credit.

A recent example of a discovery with a similar controversy was the race to discover the virus responsible for what became known as AIDS. While scientists now believe that humans became infected with HIV as far back as the 1920s, the disease first entered medical consciousness in 1981, with five documented cases of mysterious ailments in young men living in Los Angeles whose immune systems stopped working. From there, a firestorm of research started with two main facilities, the National Institute of Health (NIH) in America and the Pasteur Institute in France. The scientists at the center of the research, Bob Gallo at the NIH and Luc Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute both claimed responsibility for discovering the virus.

Montagnier was the first to publish his team's findings on the retrovirus, which they called lymphadenopathy associated virus (LAV). Shortly thereafter, Bob Gallo published his team's findings, calling the virus HTLV-III because it was similar to the human T-lymphotropic virus, responsible for a type of leukemia. However, it was Gallo who first filed the patent for a blood test based on the discovery. Gallo's research involved samples that had been provided by Montagnier, and the fact that he failed to mention this in his published findings did much to upset the French team. This set off a wave of legal and public recriminations, with the French suing in 1985. It was not until 1987, four years after both the NIH and the Pasteur Institute published their research, that the parties reached a resolution. The name of the virus, HIV, was a compromise between the two labs, and it was ruled that they would share credit and royalties from the patent. In 1991, independent analysis confirmed that the Pasteur Institute was the first to find HIV, and in 2008, the Nobel Prize went to Montagnier and his colleagues. While shut out of the Nobel, Gallo still had a significant role in the discovery process.

While HIV and CRISPR involve different areas of scientific study, the competition for credit for the rightful "discoverer" was a challenge in both cases. The identification of HIV was more time-sensitive, as the infection rates spiked after the initial reporting in the early 1980s, resulting in both the French and American government-run scientific institutes' hunt for the source so that work could begin on finding preventative measures and/or a cure. For CRISPR, there was less of a time-critical threat, but still great potential in terms of medical advancement. The cooperation between countries proved far different, as an American and a French scientist worked together to make the CRISPR discoveries. But Jennifer Doudna did have conflict with peer competitors like Zhang and with outside, private interests who seek to monetize the CRISPR medical potential.

The discoveries of CRISPR and HIV are critical successes in scientific research. They are not the first examples of long legal and political battles for establishing credit, and they will not be the last.

Luc Montagnier (left) and Robert Gallo (right), courtesy of Princess of Asturias Foundation

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Code Breaker. It originally ran in May 2021 and has been updated for the

May 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Code Breaker. It originally ran in May 2021 and has been updated for the

May 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.