Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

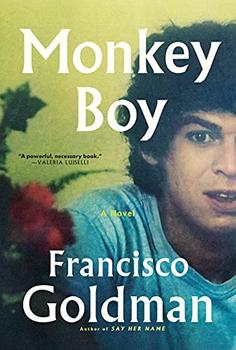

This article relates to Monkey Boy

The narrator of Francisco Goldman's autobiographical novel Monkey Boy, like Goldman himself, was a journalist who reported on the Guatemalan Civil War. The brutal war began in 1960 and lasted a total of 36 years. Over 200,000 were killed or "disappeared," more than 600 villages were attacked or completely destroyed by the army and 150 million people were displaced. Approximately 83 percent of the victims were Indigenous Maya, and 93 percent of human rights violations were carried out by the army and its paramilitary groups. Repercussions from the war still reverberate through the country today, and reconciliation remains elusive.

The narrator of Francisco Goldman's autobiographical novel Monkey Boy, like Goldman himself, was a journalist who reported on the Guatemalan Civil War. The brutal war began in 1960 and lasted a total of 36 years. Over 200,000 were killed or "disappeared," more than 600 villages were attacked or completely destroyed by the army and 150 million people were displaced. Approximately 83 percent of the victims were Indigenous Maya, and 93 percent of human rights violations were carried out by the army and its paramilitary groups. Repercussions from the war still reverberate through the country today, and reconciliation remains elusive.

Background

The seeds of the civil war found fertile ground following the 1954 military coup that toppled President Jacobo Arbenz, a progressive, democratically elected leader, and installed a military dictator, Colonel Castillo Armas. The United Fruit Company, which extracted huge profits from Guatemala from banana exports, had become alarmed by Arbenz's reforms that expropriated idle land and gave it to poor rural farmers. President Eisenhower had deep connections to United Fruit. The director of the CIA had served on their board of trustees, and Eisenhower's personal secretary was married to the company's chief PR officer. In the midst of the Cold War, he was also concerned about the spread of communism. The US-backed coup was orchestrated by the CIA. Once in power, Armas canceled the agrarian reforms, took away voting rights from illiterate Guatemalans, and implemented a series of repressive policies that resulted in the imprisonment of thousands of people.

The Civil War

The civil war began when left-wing guerillas, supported by Indigenous Guatemalans demanding social and economic justice, clashed with the state's military. The government responded with brutal force. According to a PBS Frontline report, "By March 1971, there had been more than 700 political killings. The victims included labor leaders, students and politicians." Violence continued to escalate in the '70s and '80s. According to Frontline, during this time, "At least 50,000 people died in the violence, and 200,000 Guatemalans fled to neighboring countries. Hundreds of thousands more were internally displaced because of systematic repression by the military."

The worst atrocities occurred during the 1980s, particularly under General Efrain Rios Montt, who seized power in another military coup in 1982. During that time, the government initiated a policy "aimed at ending insurgent guerrilla warfare by destroying the civilian base in which they hid." The army and its state-sponsored death squads swept through the country with a "scorched earth" policy, razing Indigenous villages, poisoning crops and water supplies, and murdering the inhabitants, burying them in mass unmarked graves. Anyone suspected of collaboration with the rebels was arrested or kidnapped. Some ended up in secret prisons where they were raped, tortured and murdered.

Fearing the spread of communism from Cuba, the US provided monetary and tactical support throughout the war, including the training of the most feared and brutal special forces counter-insurgency unit, the Kaibiles. In 1978, President Carter barred all sales of military equipment to Guatemala due to humanitarian concerns, but in 1983, President Reagan lifted the embargo, helping fuel the bloodiest years of the conflict.

Following the awarding of the 1992 Nobel Peace Prize to Rigoberta Menchu, a Mayan human rights activist, international pressure against the war intensified. Negotiations began between the government and leftist insurgents in 1994, and in December 1996, a peace agreement was signed between the government and the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unit, officially ending the civil war. A condition of the UN-sponsored agreement was the establishment of the Commission for Historical Clarification, or CEH, to, "clarify human rights violations related to the thirty-six-year internal conflict… and to foster tolerance and preserve memory of the victims."

Aftermath

The CEH identified over 600 massacres. They concluded that between 1981 and 1983, in four predominantly Mayan regions, the actions of the Guatemalan army rose to the level of genocide.

Justice remains elusive. Thousands of families have yet to discover the fate of their loved ones, and without closure, wounds do not heal. Convictions for atrocities have largely been for minor players, although in 2011, four Kaibiles were sentenced to 6,060 years in prison for participation in the Dos Erres massacre. In 2013, General Efrain Rios Montt was tried and convicted in Guatemalan court for crimes against humanity, but his conviction was quickly overturned. He died in 2018 while awaiting a retrial. With the 2019 election of right-wing politician Alejandro Giammattei, a former doctor and prison director, many fear that further accountability efforts will be stalled.

Shrine dedicated to Bishop Juan Gerardi and victims of the Guatemalan genocide, courtesy of Adam Jones/Flickr

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Monkey Boy. It originally ran in June 2021 and has been updated for the

May 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Monkey Boy. It originally ran in June 2021 and has been updated for the

May 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

When men are not regretting that life is so short, they are doing something to kill time.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.