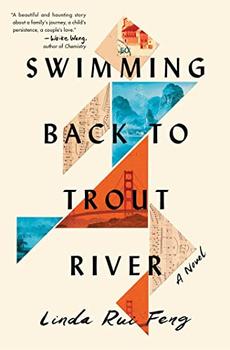

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Swimming Back to Trout River

In Swimming Back to Trout River, Dawn and Momo are united by their love of music during the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution, particularly Western classical music. There is a special significance attached to a bust of Beethoven within the novel. Beethoven was seen as a revolutionary symbol throughout 20th century China, since his personal hardships resonated with Chinese cultural ideals about struggle and triumph. Yet, Beethoven, along with all other Western music, was banned during the 10 years of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

In Swimming Back to Trout River, Dawn and Momo are united by their love of music during the turbulent years of the Cultural Revolution, particularly Western classical music. There is a special significance attached to a bust of Beethoven within the novel. Beethoven was seen as a revolutionary symbol throughout 20th century China, since his personal hardships resonated with Chinese cultural ideals about struggle and triumph. Yet, Beethoven, along with all other Western music, was banned during the 10 years of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976).

Prior to the onset of the Cultural Revolution, there was much cultural interchange between China and the West, with Shanghai dubbed "the Paris of the East" as early as 1869, and the introduction of Western-style orchestras in 1879. The growing interest and fusion of Western and traditional Eastern styles of music was brought to a sudden halt with the advent of the Cultural Revolution. The Cultural Revolution was a sociopolitical purge that sought to establish a radical proletariat by stamping out any signs of intellectualism, bourgeoisie tendencies, or "old" ways of thinking. It was brought about by Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Communist Party, in an attempt to preserve Chinese communism by eliminating any other belief systems or cultures, including not just Western influences, but also traditional Eastern beliefs that predated Maoism.

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution when it was at its most radical, both Western and Classical Chinese music were attacked for being anti-proletarian. These attacks were instigated by the Red Guards, a group of youths that were mobilized and militarized by Mao Zedong in the early years. Music in general, even traditional Chinese music, was believed to be characteristic of the bourgeoisie — and if it was Western music, that was an even more insidious form of anti-Communist sentiment. Listening to Western music was seen as a form of rebellion, and in the most extreme instances, Western music lovers faced the risk of execution. The only acceptable form was pre-approved music that conformed to Maoist revolutionary ideology. People who strayed from pre-approved cultural artworks and belief systems were dubbed "class enemies" and were socially ostracized or even physically harmed. Lu Hongen, conductor and timpanist for the Shanghai Symphony, was arrested for espousing pro-Western, anti-Communist views, and he is said to have asked his cellmate to "go to Beethoven's grave ... and tell him that his Chinese disciple was humming the Missa solemnis as he went to his execution."

The revolutionary fervor that sparked the Cultural Revolution began to ebb in 1968 with the dissolution of the Red Guards, and by 1969, there was some space for cultural performance. Chinese traditional music was permitted if it could be given a revolutionary sheen, but the prohibition on Western music was still staunchly maintained. It was only upon the death of Mao Zedong on September 9, 1976, that the Cultural Revolution came to an end. In March 1977, the Beijing Central Philharmonic Orchestra performed Beethoven's Fifth Symphony and the concert was played over the radio. The event is remembered for breaking a silence that had lasted for over a decade.

Portrait of Ludwig van Beethoven when composing the Missa Solemnis, 1820 by Joseph Karl Stieler

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Swimming Back to Trout River. It originally ran in June 2021 and has been updated for the

May 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Swimming Back to Trout River. It originally ran in June 2021 and has been updated for the

May 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.