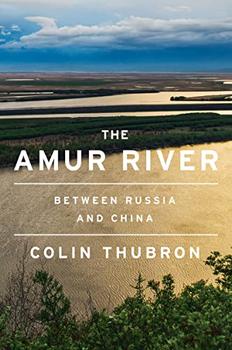

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Between Russia and China

by Colin ThubronThis article relates to The Amur River

In The Amur River: Between Russia and China, Colin Thubron engages with people from a variety of cultural backgrounds. One of these individuals is Alexei, an Amur Cossack who proudly meets the author decked out in his ceremonial uniform, yelling exuberantly "the Cossacks are coming back!" But who are the Cossacks?

In The Amur River: Between Russia and China, Colin Thubron engages with people from a variety of cultural backgrounds. One of these individuals is Alexei, an Amur Cossack who proudly meets the author decked out in his ceremonial uniform, yelling exuberantly "the Cossacks are coming back!" But who are the Cossacks?

First, the term "Cossack." Traditionally, they are a member of one of the autonomous communities drawn from various ethnic and linguistic groups (such as Slavs, Tatars and Circassians) that formed in Ukraine, southern Russia, the Caucasus Mountains and Siberia beginning in the 15th century and that were completely incorporated into czarist Russia during the 18th and 19th centuries.

The word "Cossack" is Turkic in origin and essentially translates to a "free man, a vagabond, a fortune seeker." The first translation seems most appropriate as autonomy was a primary characteristic of the Russian or Ukrainian Cossack. The Cossacks of the 14th and 15th centuries survived in fortified villages in the free lands of southern Russia, protecting themselves from roving nomadic groups and far away from the prying eyes of duchies and growing government centralization that included taxes and serfdom. They often accepted peasants escaping serfdom from Poland and Russia into their ranks. But it was when some of the Cossack groups united into a self-governing warrior organization sworn to protect the Russian czar that their reputation began to rise.

The Cossack lifestyle was a military and communal one. Sharing land and living together, Cossacks prided themselves on their superior horsemanship and battle skills. At birth, a male child's tiny hand was placed upon a weapon, and by three years of age, many Cossacks were already riding horses. The supreme military leader of a Cossack "host" (or army) was known as the ataman, or army chief, and at the height of their power, there were at least 20 different Cossack hosts spread throughout the Russian Empire.

Since they were semi-independent, states sought to harness their elite military prowess for their own purposes. Poland enlisted Cossack armies to protect its borders in the 16th century, and the Russians used them to expand the empire and defend the frontier. Cossacks stood guard against the enemies of the medieval principality of Moscow and fought battles alongside its ruling princes, particularly against the incursions of nomadic Tatars. But the Cossacks could never truly be controlled, as their free way of life at times was at cross-purposes with the Russian government — as when they raided the neighboring Ottoman Empire, even as Russia tried to maintain peace. This would become a problem over time, as Russian czars began to fear and resent Cossack independence.

When there were no battles to be fought or defense needed, Cossack armies easily disbanded, and individuals went back to living their lives on the steppe. Freedom was their byword in all things except when called upon by the Russian government to fight: "They were free from capital tax, from recruitment, and other taxes, but were strictly obliged to appear to be drafted – armed and on a horse at the first call of the central administration," according to Russian historians.

But their autonomy came to an end during the 17th and 18th centuries as the Russian Empire expanded and took in the previously "free lands" of the south. Despite several rebellions against the state, the Cossacks eventually lost their autonomous status and became yet another "denomination among the Russian people, with certain privileges and responsibilities." Today, there are hundreds of Cossack organizations in Russia striving to rebuild their historical traditions and political structures. In Colin Thubron's The Amur River: Between Russia and China, Alexei proudly shares these traditions, dreaming of a time when the Cossack way of life will indeed return.

Siberian Cossack member of the Russian Army, circa 1890s

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Amur River. It originally ran in November 2021 and has been updated for the

September 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Amur River. It originally ran in November 2021 and has been updated for the

September 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.