Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth

by Ben RawlenceThis article relates to The Treeline

In his book The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth, Ben Rawlence describes how global warming is altering northern ecosystems like the tundra of Siberia. As temperatures rise, the permafrost no longer lives up to its name; instead of staying permanently frozen, the ice within is melting. This causes the ground to collapse into sinkholes as the water drains away, or the soil turns to slush underground, as Siberian scientists are finding.

In his book The Treeline: The Last Forest and the Future of Life on Earth, Ben Rawlence describes how global warming is altering northern ecosystems like the tundra of Siberia. As temperatures rise, the permafrost no longer lives up to its name; instead of staying permanently frozen, the ice within is melting. This causes the ground to collapse into sinkholes as the water drains away, or the soil turns to slush underground, as Siberian scientists are finding.

As it warms, the permafrost releases greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide and methane, that have been trapped in the ice for eons. This aggravates the warming that is causing the melting in the first place, since these gases trap more heat in the atmosphere and warm the ground temperatures further.

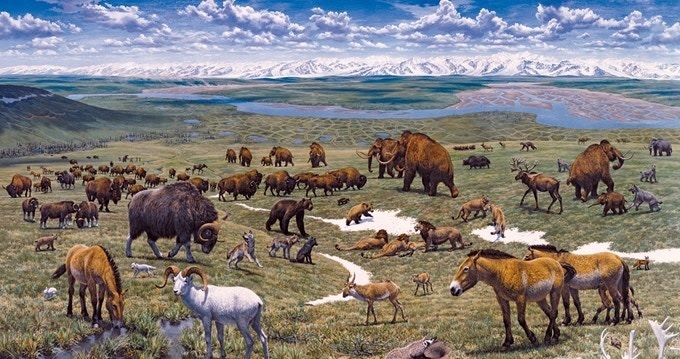

In a bid to stop this runaway feedback loop, scientists are advocating to reintroduce large mammal species that may be able to restore tundra ecosystems and slow down the melting of the permafrost. As Joshua Yaffa explains in his recent piece "The Great Siberian Thaw," "During the Pleistocene era, the Arctic was covered by grassy steppe, which acted as a natural buffer for the permafrost. The mammals that roamed this lost savanna depended on it for food and also perpetuated its existence." Russian scientists Sergei and Nikita Zimov, a father-and-son team working in Siberia, are aiming to recreate this steppe landscape, rather than maintain the larch forests that have expanded across Siberia since the extinction of woolly mammoths and other large grazers thousands of years ago.

This is because forests trap snow, and snow acts as a blanket on land. Under a thick blanket of snow, the ground temperatures stay warmer. Conversely, with less snow cover the ground is exposed directly to cold air and wind, and Zimov and other scientists believe this can slow down the melting of the permafrost.

Large grazing animals play a role because they eat shrubs, seedlings and brush, naturally cutting down the forest or stopping it from spreading. They dig into the snow to paw at the ground for food, churning over the soil, all of which helps steppe grasslands flourish at the expense of large trees and forests. The Zimovs established a park in the late 1990s and brought horses, sheep, yaks and even camels to graze. Yaffa reports that a study two years ago showed that "the animals reduced average snow density by half, and lowered the average temperature of the permafrost by nearly two degrees Celsius."

There are risks with re-engineering landscapes, of course, and Yaffa notes that some scientists wonder if the number of grazing animals needed to lower snow cover is truly sustainable. It also brings up questions of what is "natural." To humans, the larch forests of Siberia are ancient, but as Rawlence explains, in geological terms, they're "a weed unleashed by human activity," namely hunting large mammals to extinction. Where do we draw the line? How do we choose the "right" landscape to recreate?

These are valid concerns and questions, yet given the risks of inaction, these reintroductions and ecological interventions may be the best way to slow the permafrost thaw, "thus buying humanity a little more time to avert catastrophic global warming," according to Rawlence. With time running low and warming — as well as fires, storms and other ecological disasters — accelerating, it may be worth a try.

Artist's rendering of Siberian steppe, courtesy of Pleistocene Park

Filed under Nature and the Environment

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Treeline. It originally ran in March 2022 and has been updated for the

December 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Treeline. It originally ran in March 2022 and has been updated for the

December 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.