Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

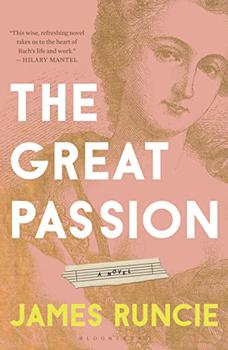

This article relates to The Great Passion

The protagonist of James Runcie's novel, The Great Passion, is an organist and organ builder. The pipe organ has been referred to as the "king of musical instruments" due to its size, complexity and power. Though its structure is similar to that of a piano, it has not one keyboard but as many as seven, plus a pedalboard played with the feet, and sometimes hundreds of "stops" on the console that are manually pulled opened or pushed closed during a piece to add musical effects (e.g., producing a buzzy tone or one that sounds like a bell). A single organ can be comprised of thousands of pipes, and the organ has the largest and oldest repertoire of any instrument in Western music.

The protagonist of James Runcie's novel, The Great Passion, is an organist and organ builder. The pipe organ has been referred to as the "king of musical instruments" due to its size, complexity and power. Though its structure is similar to that of a piano, it has not one keyboard but as many as seven, plus a pedalboard played with the feet, and sometimes hundreds of "stops" on the console that are manually pulled opened or pushed closed during a piece to add musical effects (e.g., producing a buzzy tone or one that sounds like a bell). A single organ can be comprised of thousands of pipes, and the organ has the largest and oldest repertoire of any instrument in Western music.

It's believed that the earliest iteration of the organ was created by Ctesibius of Alexandria, a Greek engineer, around 200 BCE. Surprisingly, it was designed as a demonstration of hydraulics and wasn't intended to be a musical instrument at all. He inverted a bowl-shaped chamber in a tank of water, trapping pressurized air inside. A slide in the upper section of the chamber was then pulled to allow the trapped air to escape into a pipe, producing sound. The air pressure was kept constant via a piston designed to continually fill the chamber, while the water pressure from below forced the air out of the chamber at a consistent rate, thereby allowing the sound to be sustained as it exited the pipe. Ctesibius's design consisted of several pipes, each of which had its own mechanism, and he noted that pipes of differing lengths and diameters produced different tones.

The first documented use of this contraption as a musical instrument came about 150 years later, when a man named Antipatros entered a musical contest at Delphi playing a hydraulic organ to great acclaim. The machine was gradually adopted by the Romans for use in their theatres, banquet halls and arenas; the Roman Emperor Nero claimed it was his favorite instrument. The technology made its way east and was adopted in the Byzantine Empire, where the use of water to maintain air pressure was phased out, replaced by a bellows.

The skill to produce organs died out in Western Europe with the fall of the Roman Empire during the fifth century CE, even as the instrument's design continued to improve in Eastern Europe. It's believed a resurgence was prompted when the Byzantine Emperor Constantine Copronymus sent a bellows-driven organ to Pepin the Short, King of the Franks, in 757 CE. The instrument was such a hit that a demand arose for copies, at which point a skilled organ builder was sent for who proceeded to teach others how to construct them.

No one is sure precisely how the pipe organ became such an important facet of church music; indeed, early Christian churches frowned on it, since it was associated with Roman excess. One theory credits its incorporation into religious services with the rise of the Benedictine order, which seems to have encouraged organ music and polyphony (multi-part music) more than other monastic orders. Regardless, it was a fixture in Western churches by the 10th century.

As the organ grew in popularity, manufacturers competed, adding features to outdo other builders. The original sliders that allowed air into the pipes were replaced with a keyboard, where pressing a key would release the air into a corresponding pipe, and organs with 40 or more such pipes became the norm. Manufacturers experimented with pipe designs, too, discovering ways to modify them to produce different sounds. A set of pipes, or a "rank," could be installed that sounded like a bell, for example, with another rank that produced flute-like tones, and perhaps a third that mimicked a trumpet. Each of these was activated by a "stop," which when pulled allowed air to be released into the rank of pipes to produce the effect the organist was looking for. (Fun fact: This is where the term "pull out all the stops" comes from.) Over time, the number of ranks, stops and keyboards proliferated.

France became a hub for organ manufacture by the middle of the 17th century, and as more individuals were trained in the same school of construction, organs became more uniform. This standardization was also helped by the introduction of printed music, which could only be accurately performed if the instrument had the right keyboards and pipes. With the advent of the French Revolution, organ building came to a standstill and remained stagnant until another revival at the beginning of the 19th century. The introduction of the railroad allowed for easier sharing of ideas for improvement, and economic stability across Europe allowed for the construction of bigger and better organs.

Today, a simple organ might have two keyboards, plus a pedalboard and eight to 10 stops corresponding to ranks of pipes. That's the bare minimum, though, and the largest organs in the world have hundreds of stops and thousands of pipes. The organ at the National Cathedral in Washington, DC, for example, has 189 ranks with a total of 10,647 pipes operated by 200 stops. Many of the best and largest organs in the United States aren't located in churches; by many accounts, the best two are at Walt Disney Hall in Los Angeles, and the Lord & Taylor department store in Philadelphia. The largest in the country is at Boardwalk Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey. It has seven keyboards, 517 ranks and 381 stops.

Boardwalk Hall pipe organ in Atlantic City, courtesy of Historic Organ Restoration Committee

Filed under Music and the Arts

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Great Passion. It originally ran in April 2022 and has been updated for the

February 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Great Passion. It originally ran in April 2022 and has been updated for the

February 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Every good journalist has a novel in him - which is an excellent place for it.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.