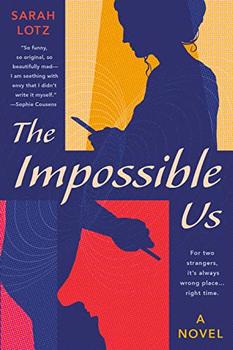

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to The Impossible Us

In The Impossible Us, Nick becomes connected with a group calling themselves the Berenstain Society. Their name is inspired by one of the most famous examples of what's popularly known as the Mandela effect. The Mandela effect, according to Medical News Today, "describes a situation in which a person or a group of people have a false memory of an event." The name was coined in 2009 after self-described paranomal consultant Fiona Broome noted on her blog that not only she, but also many other people, had vivid memories of Nelson Mandela dying in a South African jail when he was imprisoned during the apartheid period in the 1980s. Mandela, of course, did not die in prison; he went on to serve as the president of South Africa after his release, and he passed away in 2013.

In The Impossible Us, Nick becomes connected with a group calling themselves the Berenstain Society. Their name is inspired by one of the most famous examples of what's popularly known as the Mandela effect. The Mandela effect, according to Medical News Today, "describes a situation in which a person or a group of people have a false memory of an event." The name was coined in 2009 after self-described paranomal consultant Fiona Broome noted on her blog that not only she, but also many other people, had vivid memories of Nelson Mandela dying in a South African jail when he was imprisoned during the apartheid period in the 1980s. Mandela, of course, did not die in prison; he went on to serve as the president of South Africa after his release, and he passed away in 2013.

But, as Broome and others have pointed out, a not insignificant number of people misremember the facts surrounding Mandela's life and death, and much speculation has arisen about why this false memory is so prevalent. One theory (and this is the one Sarah Lotz explores in The Impossible Us) is that Broome and others like her were actually living in a parallel reality in the 1980s, one that appeared virtually identical to ours, but in which Mandela did, in fact, die in prison. In the intervening years, they've made their way across the matrix to our reality, but have maintained their memories of a different timeline.

Since Broome first named this phenomenon, other examples have arisen, primarily on social media. One of the most famous involves the children's book characters the Berenstain Bears, which many adults swear was spelled "Berenstein" in their childhood. Another is a common memory of a 1990s movie called Shazaam that starred the comedian Sinbad. Sounds plausible, right? But it turns out that movie never existed, at least not in our reality.

Is it possible that these examples (and there are many others, hinging on everything from Star Wars dialogue to the location of New Zealand) are proof that many of us spent our formative years in a different timeline and only traveled here via a glitch in the matrix? Or could there be something else going on?

Neuroscience offers some alternate (but perhaps less evocative) possibilities. Memories are stored in neural networks in the brain, with memories related to similar pieces of information (the definitions of similar words, for example) stored in close proximity to one another, but that proximity might cause a piece of information to be recalled in error. The example most often given is that Alexander Hamilton, who was a Founding Father but never president, is very often listed by Americans when asked to name presidents. Our memories related to American history or to the founding of the country are likely stored in a schema that overlaps with our knowledge of our country's presidents — so perhaps it's not surprising that Hamilton crops up inadvertently when we access that group of neural networks.

It's also probably not surprising that the Mandela effect and its manifestations have come to light primarily during the last 10-15 years, as the sharing of false memories online — often in very detailed and convincing ways — capitalizes on the human mind's openness to suggestibility, or the readiness to believe what someone else has said.

Internet trend, neuroscientific phenomenon, or the evidence of alternate parallel worlds? Whatever you believe, the Mandela effect offers a fascinating example of the mysteries of human memory.

Nelson Mandela, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Filed under Cultural Curiosities

![]() This article relates to The Impossible Us.

It first ran in the April 6, 2022

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to The Impossible Us.

It first ran in the April 6, 2022

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.