Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

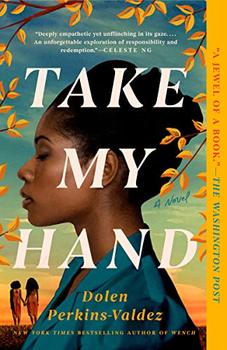

This article relates to Take My Hand

In Take My Hand, the protagonist Civil Townsend works at a family planning center in Montgomery, Alabama in 1973. She visits a Black family and administers birth control shots to two sisters, ages 11 and 13, at the behest of her supervisor, a man who later orders the girls to be sterilized. This story is based on the real-life sterilization of Mary Alice and Minnie Relf, whose mother signed a document agreeing to the procedure — with an X, because she was illiterate. The family later claimed they had been misled and sued; the class-action lawsuit launched by the Southern Poverty Law Center found many other instances of forced or coerced sterilization. Many of the victims were poor and agreed to the procedure when a doctor told them their welfare benefits could be taken away otherwise. And many were Black or members of other marginalized racial groups. Involuntary sterilization has been used as a tool for eugenics in the United States for over a century, intended to reduce the populations of racial minorities and people with mental illnesses, in particular. Both men and women have been victims of this practice, but women have been targeted at much higher rates.

According to a study by PBS, "federally-funded sterilization programs took place in 32 states throughout the 20th century." California had the highest number of incidents in the country, numbering at 20,000 sterilizations from 1909-1979, and eugenicist Harry Laughlin sent information about the California program to Germany in 1935, where it became a model for the Nazis' eugenics programs. In the early decades of the 20th century, the primary focus of sterilization programs was on the mentally ill and people with cognitive or other disabilities. The Supreme Court's decision in Buck v. Bell in 1927 upheld states' rights to forcibly sterilize a person who had been deemed "mentally deficient."

In the 1950s and '60s, as the Civil Rights movement began gaining momentum, sterilization programs shifted toward controlling the reproductive capabilities of Black people and other people of color. North Carolina had the third-highest number of sterilizations with a total of over 7,000, and from 1950-1966, Black women were being sterilized at three times the rate of white women (and more than 12 times the rate of white men). In her book Killing the Black Body: Race, Reproduction, and the Meaning of Liberty, Dorothy Roberts writes that "Teaching hospitals performed unnecessary hysterectomies on poor Black women as practice for their medical residents." The procedure under these circumstances was often referred to as a "Mississippi appendectomy" by critics.

Native American women were also targeted for sterilization during this time period. The U.S. Indian Health Service, a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, sterilized at least 3,406 Native women between 1973-1976. A study conducted during this time found that at least one in four sterilized Native women had not given consent.

Legislation was passed in 1979 that attempted to prevent federally funded sterilization. It required a person to consent at least 30 days before the procedure, and be deemed competent to do so. State sterilization laws have largely been repealed, most in the 1970s, though forced sterilization was legal in West Virginia up until 2013. However, legal scholars argue that there are "gaps in state and federal protections" as "there still has not been a sweeping declaration by the Supreme Court ruling eugenics or forced sterilization unconstitutional."

The sterilization of those deemed "unfit" to have children by the state has continued into the 21st century, despite laws prohibiting it. According to the Center for Investigative Reporting, the California Department of Corrections sterilized 150 female inmates from 2006-2010, with many of the sterilized inmates later claiming to have been coerced. There have also been recent complaints about forced sterilization of immigrant women in ICE detention centers.

Filed under Society and Politics

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Take My Hand. It originally ran in April 2022 and has been updated for the

April 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Take My Hand. It originally ran in April 2022 and has been updated for the

April 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Wherever they burn books, in the end will also burn human beings.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.