Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free

by Sarah WeinmanThis article relates to Scoundrel

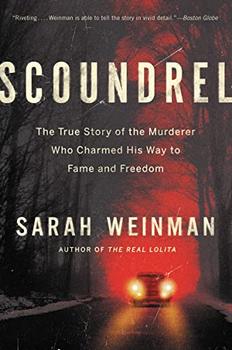

Sarah Weinman's Scoundrel: How a Convicted Murderer Persuaded the Women Who Loved Him, the Conservative Establishment, and the Courts to Set Him Free sits squarely in one of today's hottest genres: true crime. Consumers of the genre may crave the rush that comes from real-life crime stories, especially ones that prove the cliché that truth can be stranger than fiction. In addition, people are fascinated by the depths and evils of the human mind, as evinced by the success of books based on accounts of true crimes, such as In Cold Blood by Truman Capote and all-time genre bestseller Helter Skelter by Vincent Bugliosi. Norman Mailer's The Executioner's Song won the Pulitzer Prize in 1980.

Although recently re-established through prominence in podcasts and TV shows, the true crime genre has its origins centuries ago. Scottish ballads from as early as the 16th century described supposedly true stories of love and the murderous lengths to which people would go for it, and the oral-history quality of the lyrics allowed these stories to be spread far and wide even before they were written down. Puritan execution sermons, delivered by preachers about the wrongdoing of those accused of crimes before they were put to death, followed as another gory version of true crime in early America.

Some writers in the 18th and 19th centuries leaned into an aesthetic depiction of real-life crimes, like Thomas De Quincey, who wrote a narrative in 1827 describing the infamous Ratcliffe Highway murders from three perspectives: those of the killers, the victims and the members of the nearby community. Others, however, chose to approach the true crime genre from a more reform-oriented position (not unlike the contemporary example of Bryan Stevenson's Just Mercy, which is often included in true crime lists because of its attention to the legal processes involved in wrongful convictions). For example, Charles Dickens wrote "A Visit to Newgate" in 1836 to expose the deplorable conditions within the prison.

As the genre has continued to develop, multiple strands have emerged. For example, some writers address crimes decades or even centuries old, and must fill in gaps from years before more advanced scientific and investigative practices. This can lead to a somewhat more humane treatment, as the majority of those related to the crime may no longer be living. However, a major critique of the true crime genre that has emerged, particularly as the internet and social media make it far too easy to find the names of those connected with tragedy, is that the genre exploits the pain and suffering of people who often can no longer defend themselves against slander. Weinman also shows in her book how the genre itself is vulnerable to falsehoods and manipulations — through the influence he garnered, criminal Edgar Smith was able to publish a narrative maintaining his innocence, the bestselling Brief Against Death.

There are, however, styles within the genre that can combat those criticisms. For example, some writers focus more on criminal investigations than the crimes themselves, such as I'll Be Gone in the Dark: One Woman's Obsessive Search for the Golden State Killer by Michelle McNamara. Still others take one of two lenses: criminal-centric (à la Ann Rule's The Stranger Beside Me, which details her friendship with Ted Bundy) or victim-centric, a perspective which, according to Jessica Dukes, "focus[es] on the lives of the victims and seek[s] to give a voice to the lost." Of course, there are those books which combine multiple styles, such as Scoundrel, in which Weinman provides extensive biographical information from Smith's life, as well as information from his many trials, while still pursuing the ultimate goal of recognizing how his many crimes resulted in "catastrophic collateral damage to women."

While the genre certainly has caused harm to victims and their families in the past, it has also arguably addressed some of that harm, and its long history shows that it is not going anywhere anytime soon. Rather, it will continue to invent and reinvent itself, in some cases providing entertainment value to its readers, listeners and viewers, and in some a semblance of justice, recognition and peace for the victims whose stories are told.

Filed under Books and Authors

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Scoundrel. It originally ran in April 2022 and has been updated for the

February 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Scoundrel. It originally ran in April 2022 and has been updated for the

February 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.