Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to 2 A.M. in Little America

A central theme in 2 A.M. in Little America is the difficulty of distinguishing between truth and illusion, and Pushcart Prize-winning writer and journalist Ken Kalfus uses recurrent imagery throughout the novel of mirrors, lenses and reflective surfaces to symbolize the way that our perception of reality is filtered through and refracted by our own subjective experience—like the "cacophony of reflected images" Ron Patterson sees bouncing off the mirrored surfaces of a glass building he passes on the way to work.

A central theme in 2 A.M. in Little America is the difficulty of distinguishing between truth and illusion, and Pushcart Prize-winning writer and journalist Ken Kalfus uses recurrent imagery throughout the novel of mirrors, lenses and reflective surfaces to symbolize the way that our perception of reality is filtered through and refracted by our own subjective experience—like the "cacophony of reflected images" Ron Patterson sees bouncing off the mirrored surfaces of a glass building he passes on the way to work.

In a particularly suggestive scene, Ron comes across assorted tools in a science classroom that set off a cascade of memories from his own high school physics class—bits and pieces of equipment, concave and convex mirrors used to demonstrate principles of optics, and a shoebox with a lens fixed in a hole at one end.

"I had made something like this in Mr. Strauss's class," he muses about the shoebox. "When I finally had the screen correctly adjusted, I turned to look at a girl in the back of the room. She was engrossed in constructing her own device. Her image inside my box was unsubstantial, unsteady, translucently ectoplasmic, reversed. The name of the device now glimmered before me for a few moments: camera obscura."

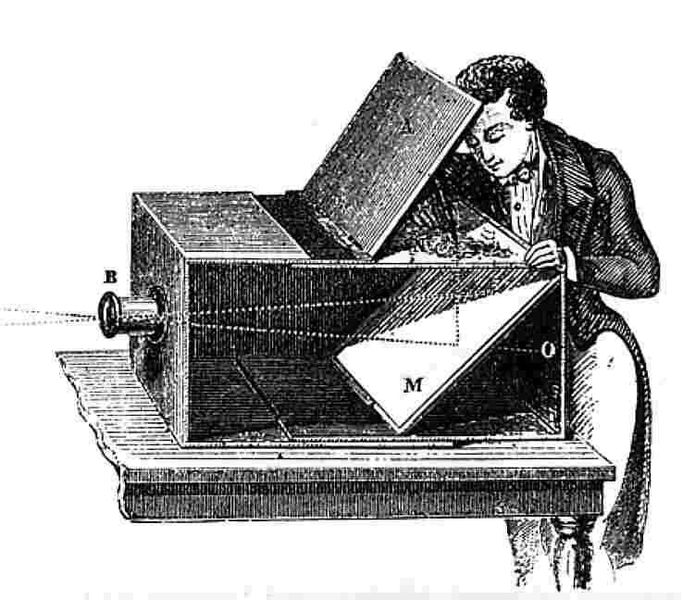

Meaning "dark room" in Latin, the term "camera obscura" was coined by German astronomer and mathematician Johannes Kepler in 1604 to describe a box-shaped device—like the one in 2 A.M. in Little America—that focuses light rays through a small opening to create an inverted image.

Centuries earlier, the Chinese philosopher Mozi (470-390 BCE) provided the first written account of the optical principle underlying camera obscura devices. Light reflected from an object travels in straight lines from its source, he observed. When projected into a dark chamber through a tiny opening, these light rays intersect at the aperture, casting a small, upside-down, reversed image of the external object onto the opposite wall—much the way that the lens of the eye focuses light through the opening of the pupil to form an image on the surface of the retina.

The earliest camera obscura devices were so large that they took up entire rooms—hence the name. In the 16th century, portable versions were developed, becoming popular among artists who used the optical tool as a drawing aid.

Adding a concave lens near the pinhole opening and an angled mirror inside the chamber sharpens the focus of the projected image and flips it right side up, allowing an artist to faithfully copy the scene onto paper—a technique thought by some art historians to have been used by Dutch masters Rembrandt (1606-1669) and Vermeer (1632-1675) to create the lifelike detail and perspective of their paintings.

In the 19th century, French scientist and inventor Joseph Niépce (1765-1833) fitted a camera obscura with a chemically coated, light-sensitive plate, creating the prototype of our modern camera and producing the world's first photograph. Depicting the view from the window of Niépce's estate, the photograph is grainy and blurred, hard to make out—like the shadowy, insubstantial figure of Ron's classmate reflected in his makeshift cardboard camera obscura in 2 A.M. in Little America.

As a symbol of the constructedness of perception, the camera obscura in the book serves as a warning against dogmatism and a reminder of the need to examine one's beliefs and assumptions with a critical eye. As Ron's physics teacher, Mr. Strauss, tells the class, perception is always mediated by the lens through which we look, and everything we think we perceive is a manifestation of the light reflecting off an object—light that can be manipulated, distorted and refracted beyond recognition.

"Remember," Ron recalls Mr. Strauss saying. "The world is real. The world is a fact. To reach that fact, however, you have to recognize how our tools of perception operate, how they're limited, what they distort, what they amplify, what they diminish, and what they leave out. But the fact is there."

Find out how to make your own cardboard camera obscura in the video below.

An artist drawing with the help of a 19th-century camera obscura. Unknown illustrator, via Wikimedia Commons

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to 2 A.M. in Little America. It originally ran in June 2022 and has been updated for the

September 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to 2 A.M. in Little America. It originally ran in June 2022 and has been updated for the

September 2022 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.