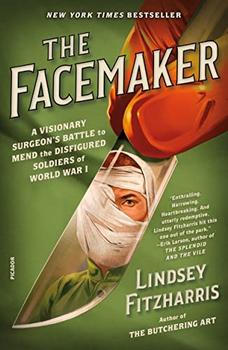

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Visionary Surgeon's Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I

by Lindsey FitzharrisThis article relates to The Facemaker

The Facemaker by Lindsey Fitzharris tells the story of Harold Gillies, a brilliant surgeon and visionary who helped pioneer the field of facial reconstruction during World War I. Through his dedication and innovation, Gillies not only restored the faces of countless soldiers, he also laid the foundation for future reconstructive work and modern-day plastic surgery. Many individuals were influenced by Gillies, including his cousin, Archibald McIndoe.

The Facemaker by Lindsey Fitzharris tells the story of Harold Gillies, a brilliant surgeon and visionary who helped pioneer the field of facial reconstruction during World War I. Through his dedication and innovation, Gillies not only restored the faces of countless soldiers, he also laid the foundation for future reconstructive work and modern-day plastic surgery. Many individuals were influenced by Gillies, including his cousin, Archibald McIndoe.

McIndoe was born in New Zealand in 1900 and graduated from medical school in 1923. He traveled to America, where he worked at the Mayo Clinic, and moved to England in 1931. When he was unable to find employment there, he reached out to his cousin, Harold Gillies, who was older by almost two decades and already well established in his career. Gillies invited McIndoe to join his private practice, and McIndoe quickly began to learn the work of a plastic surgeon.

When World War II began, Gillies and McIndoe were two of only four experienced plastic surgeons working in Britain. The four men were sent to different hospitals to serve as the heads of plastic surgery units for injured servicemen. McIndoe was sent to the Queen Victoria Hospital in East Grinstead, where he founded the Centre for Plastic and Jaw Surgery to help injured men serving in the Royal Air Force. These men often suffered from what became known as "airman's burn" — burns to the face and hands caused by burning aircraft fuel tanks.

In treating these wounds, McIndoe, like his cousin had during WWI, began to develop new surgical techniques. At the time, tannic acid was commonly used to treat burns; this compound shrank the tissue around the burn to reduce fluid loss, but the tightening of the tissues was extremely painful and left extensive scarring. McIndoe noted that pilots who crash-landed in the sea experienced less scarring than other pilots, and he started using saline baths to help begin the healing process. The use of saline solution was found to improve recovery time and survival rates, and McIndoe pushed the Ministry of Health to adopt its use as the new standard for burn management. He also developed a new skin graft technique based on Gillies' work called the walking-stalk skin graft, in which the skin to be used in grafting is formed into a tube and then "walked" gradually toward the target area.

McIndoe additionally sought to address the social ostracism experienced by soldiers with facial disfigurement. He encouraged his patients to venture into East Grinstead and interact with the community. In 1941, the Guinea Pig Club — the name referencing the experimental nature of McIndoe's treatments — was established as a social club and support group for men recovering under McIndoe's care. As the Guinea Pigs, as well as other patients, began to visit town more regularly, people became more comfortable with seeing facial injuries, and East Grinstead came to be known as "the town that never stared." In fact, many soldiers ended up marrying their nurses or women from East Grinstead, as McIndoe encouraged the locals to see the person behind the facial injuries. Being treated as typical men played a significant role in the patients' reintegration into society and their mental rehabilitation.

McIndoe died in 1960, but his legacy carried on. Members of the Guinea Pig Club honored him at their annual reunion meetings until the final meeting in 2007. The Blond McIndoe Centre was opened in 1961 and continues to fund groundbreaking research to help advance the science of healing. Queen Victoria Hospital is still known for its excellence in plastic and reconstructive surgery. In 2014, a memorial statue dedicated to McIndoe was unveiled in East Grinstead, honoring his work to help in the psychological recovery of his patients.

Much like Harold Gillies, Archibald McIndoe dedicated himself to alleviating the suffering of men, particularly airmen, injured in war. His advances regarding the use of saline are still a standard in burn management, and his work towards healing both the physical and psychological wounds of his patients bettered the lives of hundreds of injured men.

Archibald McIndoe memorial statue in East Grinstead, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Facemaker. It originally ran in August 2022 and has been updated for the

June 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Facemaker. It originally ran in August 2022 and has been updated for the

June 2023 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.