Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science

by Kate ZernikeThis article relates to The Exceptions

The discovery of DNA is one of the greatest scientific achievements in the modern era, and possibly one of the most significant in history. The credit has long gone to James Watson and Francis Crick, who publicized the famous double-helix structure of DNA and the rest, as PBS notes, "is Nobel Prize history."

The discovery of DNA is one of the greatest scientific achievements in the modern era, and possibly one of the most significant in history. The credit has long gone to James Watson and Francis Crick, who publicized the famous double-helix structure of DNA and the rest, as PBS notes, "is Nobel Prize history."

The problem is this is an oversimplification at best and a rip-off at worst. Rosalind Franklin, an English female scientist, and her co-researcher Maurice Wilkins played a crucial role in the discovery of DNA's structure, but she was written out of that history until the late 20th century.

Franklin was born to a Jewish family in London on July 25, 1920, and she studied physics and chemistry at Newnham Women's College at Cambridge University. After obtaining her PhD, she moved to Paris in 1946 to focus on X-ray crystallography, a demanding and laborious process for identifying the structure of molecules.

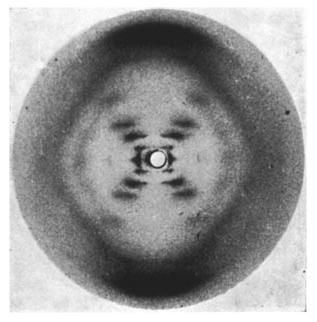

By recording and measuring the angles of scattered X-rays bouncing off atoms, crystallographers could determine the structure of those atoms and molecules. But, as Dr. Howard Markel explains in his book The Secret Life: Rosalind Franklin, James Watson, Francis Crick, and the Discovery of DNA's Double Helix, "a single X-ray image never provides the total answer. The crystallographer must rotate the specimen stepwise through hundreds of infinitesimally different angles over a spectrum of 180 (or more) degrees and take an X-ray picture at each one—and each presents its own set of smudges or diffraction patterns, making the process both time-intensive, mind-numbing, and physically cumbersome."

Franklin excelled at the work despite its difficulty. But, when she returned to England and began working at King's College, her male colleagues perceived her as difficult to work with. Franklin was known to have a forthright personality, and in the English lab this was viewed as a negative trait. Maurice Wilkins in particular was her partner in researching the structure of DNA, but he barely spoke to her out of personal dislike. Eventually, Wilkins showed one of her photographs to Watson and Crick without her knowledge. This photograph clearly showed DNA's double-helix structure, and Watson and Crick used it to build their groundbreaking model without crediting Franklin.

Watson went on to downplay Franklin's contributions in his own book, The Double Helix. He claimed she was Wilkins' assistant and was "stubborn, uptight, and resolutely unfeminine," as Kate Zernike recounts in The Exceptions: Nancy Hopkins, MIT, and the Fight for Women in Science. None of these depictions by Watson were true—Franklin was Wilkins' equal, and she wore dresses and makeup so his characterizations of her appearance were simply wrong. She was easily denigrated for traits like honesty and passion for her work that would be unremarkable or even rewarded in a male colleague.

Tragically, Franklin died at age 37 of ovarian cancer, long before Watson's book was published, and she was swept from the pages of DNA history until 1975, when Anne Sayre published Rosalind Franklin & DNA. This book began to correct the record, and as female scientists started protesting against ingrained gender discrimination in science, they saw themselves in Franklin's story.

Nancy Hopkins, protagonist of The Exceptions and student of James Watson, recognized that her mentor had misrepresented Franklin: "He had warped her to create a familiar stereotype, casting her as the 'wicked fairy' in a cautionary tale about a bright woman who dares to think there is a place for her in science," Zernike explains.

Franklin's role in the discovery of DNA has been revised in recent years, as scientists, journalists and academia have taken a closer look at the role of women and minorities in science. Yet, her story is a reminder that the double-standards women have faced in the workplace can and do have lasting consequences—and without acknowledging that reality, we won't be able to overcome inequities in pay, in academia, and in our society in general.

Image: Photograph taken by a graduate student working under the supervision of Rosalind Franklin, showing paracrystalline gel composed of DNA fiber, with a clear defraction pattern of the "B" form of DNA. It is known as Photo 51 because it was the 51st diffraction photograph taken by Franklin and Gosling.

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to The Exceptions. It originally ran in April 2023 and has been updated for the

February 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to The Exceptions. It originally ran in April 2023 and has been updated for the

February 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.