Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

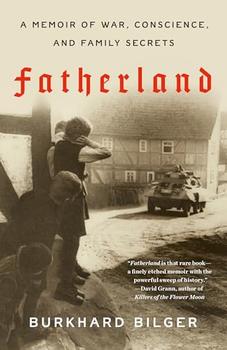

A Memoir of War, Conscience, and Family Secrets

by Burkhard BilgerThis article relates to Fatherland

In Fatherland, New Yorker staff writer Burkhard Bilger chronicles his quest to understand his maternal grandfather's Nazi past—a past shrouded in mystery despite the fact that Bilger's mother, born in 1935, was old enough at the time to have memories of World War II and her father's role in it.

In Fatherland, New Yorker staff writer Burkhard Bilger chronicles his quest to understand his maternal grandfather's Nazi past—a past shrouded in mystery despite the fact that Bilger's mother, born in 1935, was old enough at the time to have memories of World War II and her father's role in it.

She remembered her father wearing his brown uniform with a Nazi eagle on the cap and black swastika on the sleeve. She knew he had been tried and imprisoned for war crimes. Yet she had never asked him what he did during the war. Even when she went on to study the history of the era as an adult, writing her doctoral dissertation on the German occupation of France and the Vichy regime, Bilger's mother couldn't bring herself to investigate her own father's role in the war or even to talk about the little she already knew. "It must have been torment to her, trying to square what she learned about the war with her memories of her father," Bilger writes. "How could he have been both the man she loved and the monster history suggested?"

As Bilger explains in Fatherland, this reluctance to talk about World War II is widespread among Germans of his mother's generation—Germans who were born during or just before World War II and grew up in its aftermath. Dubbed the Kriegskinder, or "war children," these Germans were too young to have participated in the war but old enough to have witnessed its horrors. Like Bilger's mother, they grew up haunted by shame and guilt and hidden secrets. And despite the terrible trauma they lived through—bombs, death and wholesale destruction, lost family members, forced displacement, gnawing hunger and grinding poverty—they were taught to suppress their emotions and bury their memories. "We were told to look ahead and be happy that we were still alive, to forget everything. And that is what most of us have done," one man told Sabine Bode, a journalist who has written extensively about how repressed trauma has impacted the lives of Germans who grew up in the shadow of World War II.

Because of the collective silence surrounding their experiences, the Kriegskinder are sometimes referred to as Germany's "forgotten generation." More recently, however, there has been a surge of interest in documenting the stories of these last living witnesses—before it is too late. "As the generations turned and the war loosened its grip, people began to realize how little they knew about their parents' and grandparents' lives, and how much that silence had shaped their lives," Bilger writes in Fatherland. "They needed to hear those terrible stories after all."

For Frederike Helwig, a photographer known for her haunting portraits of Germany's Kriegskinder, preserving this disappearing generation's memories before they vanish is a crucial part of healing from and overcoming the past. "Being honest and open within a society about past crimes, mistakes, losses and emotional traumas starts an important dialogue which allows a collective reflection upon the events and presents the possibility of taking responsibility for past actions including the ability to mourn," Helwig says. "Without honesty and willingness to take responsibility for past failures and crimes, the unresolved past of a society might still influence the present. History repeats itself."

Children playing in rubble in Berlin, 1948, courtesy of the German Federal Archives

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Fatherland. It originally ran in May 2023 and has been updated for the

June 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Fatherland. It originally ran in May 2023 and has been updated for the

June 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.