Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

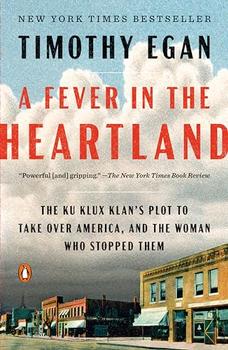

The Ku Klux Klan's Plot to Take Over America, and the Woman Who Stopped Them

by Timothy EganThis article relates to A Fever in the Heartland

Timothy Egan's book A Fever in the Heartland mentions the Women of the Ku Klux Klan, a group of women who were actively aligned with the mission of the KKK during its 1920s resurgence. In 1923, the WKKK formed in Little Rock, Arkansas. The WKKK had chapters in every state and at least 500,000 members over the course of its existence. There were certain requirements for membership: white, native-born, Protestant. Members believed in the separation of church and state, and that women shouldn't be relegated to only being housewives and mothers.

They also, like their male counterparts, were against racial mixing and thought it was a similar crime to treason. Intermingling, as they put it, was defying the laws of God and man. The Klanswomen's creed included the statement, "We believe that the current of pure American blood must be kept uncontaminated by mongrel strains and protected from racial pollution." The WKKK thought Catholicism and those who practiced it were un-American. They were vehemently in favor of immigration restrictions such as the 1924 Johnson-Reed Act, which Egan describes in his book: "Strict quotas on shunned countries slashed new arrivals from eastern and southern Europe to a bare trickle, shutting out Jews and olive-skinned Catholics. The new law made it impossible for someone from Japan to come to America legally and tightened the already harsh ban on Chinese. Africa was shut out as well."

The WKKK's mission was to purify American culture from its supposed stain of black emancipation, Catholicism and immigration. In pursuing this goal, they held meetings and ceremonies in secret. One of their more public activities was operating Klan Haven Orphanage, for orphaned children of WKKK and KKK members. But while they showed dedication to Klan ideals, misogyny directed at them from Klansmen wasn't off the table. They were also sometimes attacked with gender-based insults by their critics rather than for their beliefs: One newspaper editor characterized the WKKK as coarse women who had abandoned their families. Despite this, they soldiered on, because they believed in the cause.

"These women recall their membership in one of U.S. history's most vicious campaigns of prejudice and hatred primarily as a time of friendship and solidarity among like-minded women," writes Kathryn Blee, sociology professor and dean at the University of Pittsburgh and author of Women of the Klan: Racism and Gender in the 1920s.

The WKKK had growing pains just two years in. In 1925, a Dallas member filed a lawsuit against Robbie Gill Comer, head of the organization, and her husband for misappropriation of funds. When the records were opened, it was found that money was being used for personal expenditures by the Comers. In addition, the Klan's reputation was damaged once leader D.C. Stephenson was charged with the death of Madge Oberholtzer, a woman he kidnapped and sexually abused.

Oberholtzer wasn't affiliated with the WKKK or the Klan, but wasn't hostile to them either. The abuse she suffered made Klan and WKKK members in Indiana and elsewhere rethink their allegiance to a group they thought of as Christian, moral and decent. To them, Stephenson had been a heroic figure. He had grown the organization to states like Michigan, Ohio, Colorado and Oregon. But he had a side of himself that he kept secret from his followers until the trial.

Egan writes, "For years, politicians, ministers and apologists in the press claimed that the Klan had become such an integral part of American life—with its six million members, its senators, governors, militias, preachers, and police chiefs—was a harmless band of brothers. They were white men in hoods bonding over a shared heritage and desire for a simpler life. That image fell apart in a court of law."

As did the image of the WKKK. Although they were technically a separate organization from the KKK, in many people's minds they were the same. By the 1930s, the Women of the Ku Klux Klan were mostly silent.

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to A Fever in the Heartland. It originally ran in June 2023 and has been updated for the

June 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to A Fever in the Heartland. It originally ran in June 2023 and has been updated for the

June 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.