Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Afterlives of China's Cultural Revolution

by Tania BraniganThis article relates to Red Memory

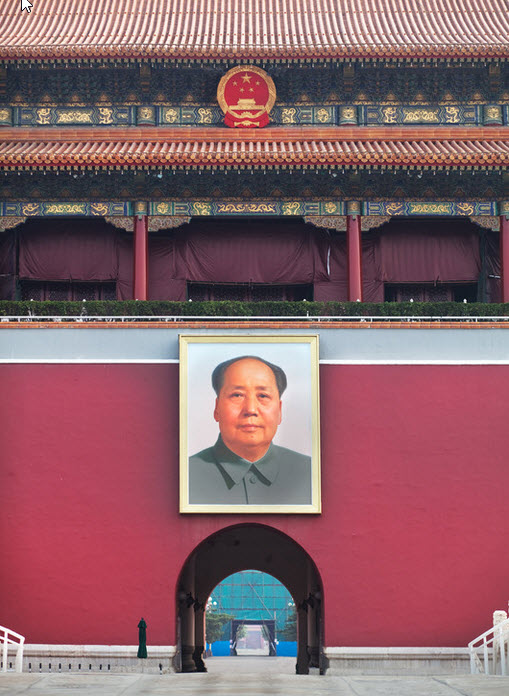

Though Chairman Mao Zedong's legacy is a contentious subject in China, his portrait still presides over the gates of Tiananmen Square, the symbolic heartland of the nation. The enormous oil painting, measuring 6.4 by 5 meters and weighing 1.5 tons, was first put in place in 1949, shortly after Mao's Communist Party wrested power from the Kuomintang. Now, decades later, Mao's portrait maintains its prestigious position, though the painting has changed somewhat since the original was created. There have been eight official renditions of Mao's portrait between the 1940s and the present day. Even when no changes are made, the painting is copied and replaced annually to ensure that the image doesn't degrade. Over the decades, the portrait has taken on a life of its own, becoming less a clear-cut endorsement of Maoist leadership than a totemic national artifact. For the government, it symbolizes the unity and strength of the Communist Party; for some people, it symbolizes China itself.

Though Chairman Mao Zedong's legacy is a contentious subject in China, his portrait still presides over the gates of Tiananmen Square, the symbolic heartland of the nation. The enormous oil painting, measuring 6.4 by 5 meters and weighing 1.5 tons, was first put in place in 1949, shortly after Mao's Communist Party wrested power from the Kuomintang. Now, decades later, Mao's portrait maintains its prestigious position, though the painting has changed somewhat since the original was created. There have been eight official renditions of Mao's portrait between the 1940s and the present day. Even when no changes are made, the painting is copied and replaced annually to ensure that the image doesn't degrade. Over the decades, the portrait has taken on a life of its own, becoming less a clear-cut endorsement of Maoist leadership than a totemic national artifact. For the government, it symbolizes the unity and strength of the Communist Party; for some people, it symbolizes China itself.

Mao's likeness has shapeshifted in subtle ways, as the painting has been continuously worked on and replaced. The first artist commissioned to lead the creative team behind Mao's portrait was Dong Xiwen. Xiwen is significant as he was one of the early adopters of a Western style of oil painting in China. Though oil painting had existed in China since the sixteenth century, traditional Chinese art incorporated a range of media, including charcoal and ink. Oil paint, however, was eventually recognized as particularly suitable for creating realistic depictions, which naturally suited Mao's interest in socialist realism as a style of art. The more widespread adoption of a Western style of oil painting also coincided with changing attitudes in China towards "Western knowledge", which had previously been referred to as "yixue" (barbarian learning).

Xiwen's portrait was completed and hung on February 12, 1949. Since then, various other artists have helmed the committee that recreates the portrait, sometimes making small alterations. The painting occasionally changes in emotional tone. In some versions, Mao's expression is stern and patriarchal; in others, warmer and more enigmatic. The most obvious alterations involve the ears. In the eight different renditions that exist so far, the perspective on Mao's pose has shifted slightly. The first portrait is full-frontal, showing both ears (to show that he is "listening to the people"); the second shows Mao from the left, with only one ear; the fourth from the right, with one ear; the fifth again from the left; the sixth with two ears again; the seventh from the left; and the current, final portrait, with both ears again. These metamorphoses give the painting a curious animation, as if the man is still alive. A new copy of the portrait is installed each September, with each previous canvas being painted over in white and held in storage.

Due to its political and cultural significance, Mao's portrait has occasionally been the target of expressive vandalism. During the 1989 pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square, which resulted in potentially thousands of deaths and hundreds of imprisonments, the portrait was vandalized in a display of anger towards the corruption and oppressive policies of the Chinese Communist Party, then under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. Yu Dongyue, along with Yu Zhijan and Lu Deching, threw black and red paint on the portrait during the violent upheaval. Each served more than a decade in prison for the act. In 2007, a man was arrested for allegedly throwing a burning object at the portrait, though the reasons for this are less clear. In 2010, a man identified by police as "Mr. Chen" was detained for allegedly throwing ink on the portrait. Most recently, in 2014, Sun Bing was sentenced to 14 months in prison, also for throwing ink on the portrait.

Despite its contentious subject matter, Mao's portrait remains an important piece of cultural iconography for China. Varying sentiments towards the image reflect Mao's legacy, which, as reported in Tania Branigan's Red Memory, is remembered by some with nostalgia, others with fear and horror. Professor Wu Hung, who grew up in Beijing and has written a book on Tiananmen Square as a political space, believes that the portrait is "a very complex image." However, it is also, he claims, "the most important painting in China."

A photograph of Mao's portrait hanging in Tiananmen Square, courtesy of Canva

Filed under Music and the Arts

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Red Memory. It originally ran in June 2023 and has been updated for the

June 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Red Memory. It originally ran in June 2023 and has been updated for the

June 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

More Anagrams

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.