Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

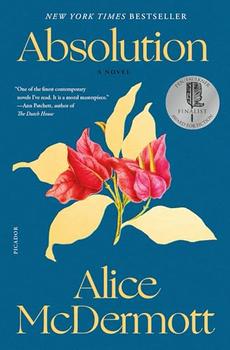

A Novel

by Alice McDermottThis article relates to Absolution

Alice McDermott's novel about the humanitarian efforts of American corporate wives living in Vietnam in the early '60s, Absolution, takes a detour to New York City in the previous decade, where Tricia, the protagonist, and her radicalized friend Stella participate in sit-ins against the compulsory Cold War duck-and-cover drills.

Alice McDermott's novel about the humanitarian efforts of American corporate wives living in Vietnam in the early '60s, Absolution, takes a detour to New York City in the previous decade, where Tricia, the protagonist, and her radicalized friend Stella participate in sit-ins against the compulsory Cold War duck-and-cover drills.

In 1954, the U.S. Federal Civil Defense Agency inaugurated an annual civil defense preparedness drill, dubbed Operation Alert, in which everyone in big cities ("target areas"), like New York, was instructed to duck and cover for fifteen minutes, ostensibly to practice bracing themselves for an attack from the Soviet Union. During that same interval, federal alert systems throughout the country were tested, government officials evacuated their stations, and even President Eisenhower took shelter in a tent city close to the White House. Failure to participate could result in a $500 fine and year-long jail sentence.

A group of 27 pacifists sat out the first fifteen-minute exercise on park benches in NYC's City Hall Park, in front of reporters and police, who eventually arrested them. As they put it in the pamphlets they handed out, they recognized the drills to be a sham, "[i]n view of the certain knowledge…that there is no defense in atomic warfare," and "a military act in a cold war to instill fear, to prepare the collective mind for war."

Among this small group was Dorothy Day (1897-1980), cofounder of the Catholic Worker Movement, a social justice program intended to unite workers and intellectuals towards community-oriented goals. McDermott's fictional Tricia comes from a working-class Catholic background, and her friend Stella, though she finds Dorothy Day humorless and her acolytes annoying, is a regular Catholic Worker volunteer.

While resistance to Operation Alert had a slow start, it can now be viewed as having helped catalyze the mainstream peace movement. To undermine the drill of 1960, hundreds of protesters, including Norman Mailer and other notables, were drawn to Manhattan by a group of disillusioned young mothers who urged them to dress respectably and take their children along with them. In 1961, the number of protestors had grown to two-and-a-half thousand. Additionally, there were now nonparticipants in other states and some East Coast colleges. By 1962, realizing the drills were strategically counterproductive, the federal government ended them.

In a letter composed in jail to fellow Catholic Worker Charles McCormick in 1957, Dorothy Day wrote, "we do not want to harass people who are only doing their duty…although we break one law in order to make our point clear about our refusal to cooperate with psychological warfare, we bend over backward to show our respect for the desire for the common good which most laws are for." Perhaps the conciliatory tone of these words might ring too soft to us nowadays, but the letter captures the spirit of an anti-authoritarian movement that achieved its ends fairly quickly through civil disobedience. While Absolution's Stella doubts the effect that "the voice of the masses," can have—she refers to it as an "incoherent din"—in this instance, history provides a hopeful counterexample.

Dorothy Day at Subiaco Abbey in 1952, via Wikimedia Commons

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Absolution. It originally ran in January 2024 and has been updated for the

October 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Absolution. It originally ran in January 2024 and has been updated for the

October 2024 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Harvard is the storehouse of knowledge because the freshmen bring so much in and the graduates take so little out.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.