Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

The Revolutionary Life of Margaret Cavendish

by Francesca PeacockThis article relates to Pure Wit

In her biography of 17th-century author Margaret Cavendish, Pure Wit, Francesca Peacock shines light on often-overlooked aspects of Cavendish's life and work, including her contributions to Western philosophy. From the beginning of her philosophical career, she believed in materialism. Simply put, this is the theory that everything that exists is material and that the events we observe in the world are the result of interactions between matter.

In her biography of 17th-century author Margaret Cavendish, Pure Wit, Francesca Peacock shines light on often-overlooked aspects of Cavendish's life and work, including her contributions to Western philosophy. From the beginning of her philosophical career, she believed in materialism. Simply put, this is the theory that everything that exists is material and that the events we observe in the world are the result of interactions between matter.

This theory rejects the idea of an incorporeal spiritual world—in a materialist view, the soul is either made up of matter like the physical world, or does not exist. In her early writings, Cavendish was a proponent of atomism, a branch of materialism that suggests that the universe is made up of unchangeable pieces, or atoms, in a void. A version of atomism would be proven by scientific experimentation starting in the 19th century, but in Cavendish's day atomist theories were based on Ancient Greek ideas.

However, while Cavendish would continue to support materialism, the form she believed matter took changed quickly. In 1656, she published A Condemning Treatise of Atomes, arguing that atomist theories couldn't explain either the variety or the order seen in the natural world. To explain these things, she turned to vitalism. Vitalism is a school of thought dating back to Aristotle which argues that the existence of living things depends on a vital force that allows them to grow and function.

Within this framework, she developed her idea of three types of matter—rational matter, sensitive matter, and inanimate matter. In her view, rational matter was the type that produced thought and order, while sensitive matter was influenced by rational matter, and inanimate matter was used as a building material by the other two. This is a hierarchical, top-down view of existence that Peacock connects to Cavendish's strong belief in monarchy as the proper form of government.

Even in Cavendish's time, vitalist philosophies were strongly opposed by mechanistic ones. Mechanism asserts that the natural world can be explained through physical laws that determine how matter interacts, rejecting both the idea of a vital force and the existence of the incorporeal. However, other philosophers continued to support vitalism, such as the 18th-century Denis Diderot who, similarly to Cavendish, argued for living matter. The debate continued, with vitalism becoming less popular as more and more of the phenomena that earlier philosophers argued could not exist without a vital force were explained by chemistry or physics.

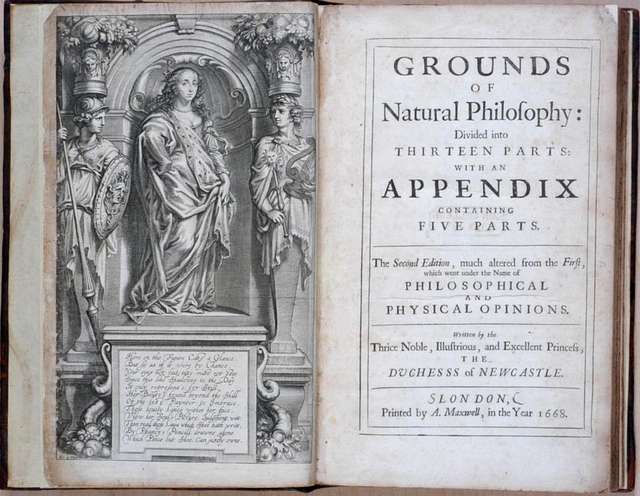

Margaret Cavendish's 1668 Grounds of Natural Philosophy, via Picryl

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This article relates to Pure Wit.

It first ran in the February 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Pure Wit.

It first ran in the February 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.