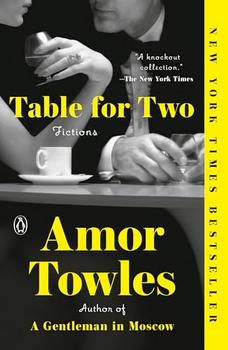

Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

Fictions

by Amor TowlesThis article relates to Table for Two

In the novella "Eve in Hollywood," in Amor Towles's Table for Two, Eve Ross becomes close friends with the actress Olivia de Havilland. It is 1938, and de Havilland's popular new film The Adventures of Robin Hood has just been released. All is not well in paradise, however, for the young star falls prey to blackmailers, even as she struggles to wrest more control over her career from a paternalistic Hollywood studio. While the first plot point is pure fantasy, the second, in fact, accurately reflects the real Olivia de Havilland's struggles with the Hollywood studio system.

Olivia de Havilland (b. 1916) and her younger sister Joan (b. 1917, later known as the actress Joan Fontaine) were born in Japan to British parents, but grew up in the California town of Saratoga. After high school, a teenage de Havilland was cast as second understudy for the role of Hermia in a splashy Hollywood Bowl staging of A Midsummer Night's Dream, produced by Max Reinhardt. When both the actress playing Hermia and the first understudy dropped out only one week before the play's premiere, de Havilland stepped into the plum role. In the subsequent film version Reinhardt made for Warner Bros., he again cast de Havilland as Hermia.

In November 1934, de Havilland signed a standard seven-year contract with Warner Bros., with a starting salary of $200 a week (about $4,600 today). De Havilland entered the film business during a period known as the golden age of the Hollywood studio system. Its five major studios—Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM), RKO, 20th Century Fox, Warner Bros. and Paramount Pictures—followed a business strategy known as vertical integration through which "they owned all aspects of production, distribution, and exhibition," according to writer Mike Maher. "From before cameras started rolling until the theaters projectors stopped, the entire process was controlled by the studios." And for contracted actors, powerful executives dictated all aspects of life, including molding their public image and deciding which roles they would take.

In the first year of her contract, Warner Bros. cast 18-year-old de Havilland to star with 25-year-old actor Errol Flynn in the action-adventure film Captain Blood. Flynn and de Havilland would go on to make several films together, the most popular being The Adventures of Robin Hood. Although these films did well at the box office, de Havilland began to grow frustrated with the characters she was playing. In an interview, de Havilland explained: "The life of the love interest is really pretty boring.…The heroine has nothing much to do, except encourage the hero…. I longed to play a character who initiated things, who experienced important things, who interpreted the great agonies and joys of human experience. I certainly wasn't doing that on any level."

In the first year of her contract, Warner Bros. cast 18-year-old de Havilland to star with 25-year-old actor Errol Flynn in the action-adventure film Captain Blood. Flynn and de Havilland would go on to make several films together, the most popular being The Adventures of Robin Hood. Although these films did well at the box office, de Havilland began to grow frustrated with the characters she was playing. In an interview, de Havilland explained: "The life of the love interest is really pretty boring.…The heroine has nothing much to do, except encourage the hero…. I longed to play a character who initiated things, who experienced important things, who interpreted the great agonies and joys of human experience. I certainly wasn't doing that on any level."

In December of 1938, de Havilland got a call from George Cukor, who was preparing to direct the film Gone with the Wind for David Selznick and MGM. He asked her if she would be interested in playing the coveted role of Melanie Hamilton. She was thrilled at the opportunity, but her contract required her to get permission from Warner Bros.'s infamously hard-nosed executive, Jack Warner. She later recalled that Warner "utterly refused to lend me for Melanie…. I even went to call on him and begged him. He said, no." Desperate, de Havilland made a bold move. She called Warner's wife, Ann, herself a former actress, and asked her to help: "Through her, Jack eventually agreed." The film became an instant classic, and de Havilland received a best supporting actress Oscar nomination.

In 1943, just as de Havilland looked forward to the end of her contract with Warner Bros., the studio announced that they would not release her until she had repaid them for time lost by her previous contract suspensions with another film. This was business as usual for big studios, which punished actors who rejected assigned roles by extending the length of their contract for the time it took another actor to complete the role. De Havilland sued Warner Bros., arguing that "the contract was for seven years, suspension or not, and that Warner Bros. was violating labor law." This led to a difficult, drawn-out trial in which Warner lawyers goaded her to make her look unreasonable. The strategy backfired. The court ruled in her favor, declaring that "the actress's contract was a form of 'peonage' or illegal servitude." The actress not only won her case but saw it become a landmark judgment still known as the "de Havilland law." Many think this marked the beginning of the end for the Hollywood studio system, which, in 1948, was forced in a major anti-trust decision to begin dismantling vertical integration.

Although Warner Bros. tried to ruin de Haviland's career, she persevered, achieving greater fame and eventually capturing two Academy Awards. However, as film professor Jeanne Basinger comments, "Other actresses have won Academy Awards. Other stars have been as famous. But few had as far-reaching an impact as de Havilland did," thanks to her stellar performance under a different spotlight in a court of law.

Olivia de Havilland and Errol Flynn in The Adventures of Robin Hood trailer, courtesy of Warner Bros.

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This article relates to Table for Two.

It first ran in the April 3, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Table for Two.

It first ran in the April 3, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

When all think alike, no one thinks very much

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.