Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Rachel KhongThis article relates to Real Americans

May, the matriarch of Rachel Khong's Real Americans, is born into a poor rural Chinese family in the 1950s. Her fate is foretold by her mother's life: wake before dawn to cook breakfast, clean up after the men in the family, head to the rice paddies and toil until the time to head home to cook supper, rinse and repeat. It is backbreaking. Luckily for May, she possesses an academic gift and an intellectual curiosity that missed her elder brothers. She excels at the National Exam, testing into esteemed Peking University to study biology. Her tuition is sponsored by the state and she escapes rural poverty to become a glamorous urban student. "You look like the girl from the [propaganda] poster," May's young cousin says admiringly on her return to the village for Chinese New Year, by which she means, May looks healthy and beautiful. May is blossoming in her 20s: young, in love, free from home, and free to pursue the science she loves. But social and political changes are happening around her.

The Cultural Revolution began in May 1966 under Chairman Mao Zedong, starting first on school campuses in Beijing. The stated goal was to remake society into the communist ideal and reject the Four Olds (old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits). Anything with perceived ties to the West or to the bourgeoisie was smashed, dismantled, or violently attacked.

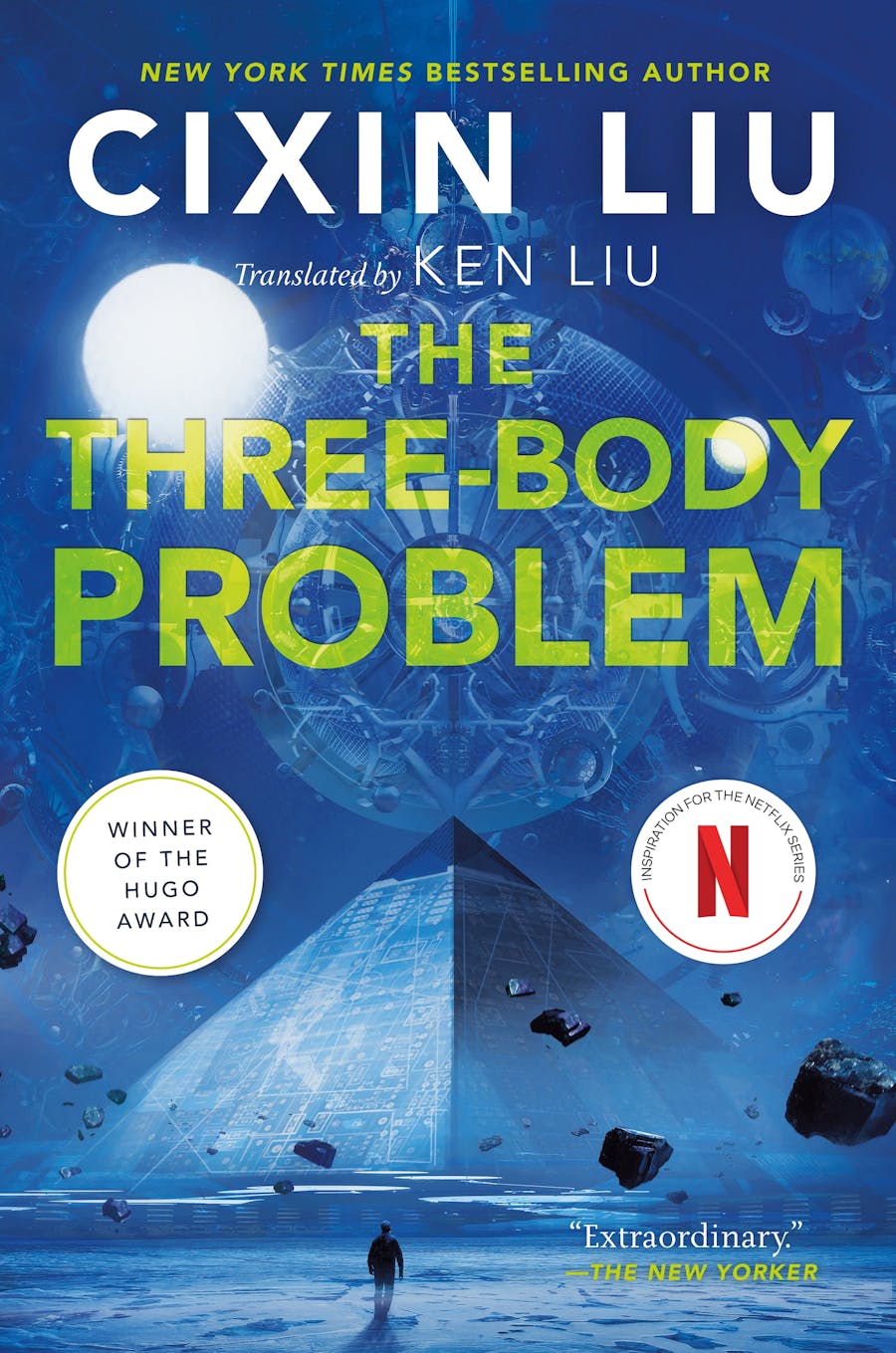

The horror unleashed towards the accused "capitalist roaders" of this period is captured in the opening scene of Liu Cixin's popular science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem. Scientists were seen as having international connections due to global cooperation in research, and their desire to question rather than accept party propaganda was taken as evidence of disloyalty to the state and revolution. Academics, including scientists and intellectuals, were denounced, their property taken, and were physically tortured or forced into hard agrarian labor. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the premier Chinese research institute, has records of 229 scientists who were killed or took their own lives during this period. While this number may seem small compared to the half to two million total lives estimated to be lost, these were just the officially recorded figures and the broader impact on the field of science and research was overwhelming. "The Cultural Revolution devastated China's science and technological undertakings," writes Chunli Bai, the current president of CAS. The national college entrance exam was closed, universities would admit no new undergraduates from 1966 to 1969 and no new graduate students through 1977, and scientific journals ceased publication.

The horror unleashed towards the accused "capitalist roaders" of this period is captured in the opening scene of Liu Cixin's popular science fiction novel The Three-Body Problem. Scientists were seen as having international connections due to global cooperation in research, and their desire to question rather than accept party propaganda was taken as evidence of disloyalty to the state and revolution. Academics, including scientists and intellectuals, were denounced, their property taken, and were physically tortured or forced into hard agrarian labor. The Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), the premier Chinese research institute, has records of 229 scientists who were killed or took their own lives during this period. While this number may seem small compared to the half to two million total lives estimated to be lost, these were just the officially recorded figures and the broader impact on the field of science and research was overwhelming. "The Cultural Revolution devastated China's science and technological undertakings," writes Chunli Bai, the current president of CAS. The national college entrance exam was closed, universities would admit no new undergraduates from 1966 to 1969 and no new graduate students through 1977, and scientific journals ceased publication.

Research became defined as an inherently political act, with everything from choice of topics to methods of investigation being seen as political. For instance, researchers could choose areas of study such as crop yield, which would benefit the masses. However, an area of study not directly beneficial to the masses or preferring an expert-driven level of experimentation would be seen as counter-revolutionary. Scientists learned to parrot political dogma, weaving it into their research and methodology to escape ostracization. This represented a sharp departure from the evidence-driven, facts-based approach of the classical scientific method and has implications even today for how Chinese research and findings are accepted by the larger scientific community.

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Real Americans. It originally ran in May 2024 and has been updated for the

March 2025 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Real Americans. It originally ran in May 2024 and has been updated for the

March 2025 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.