Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

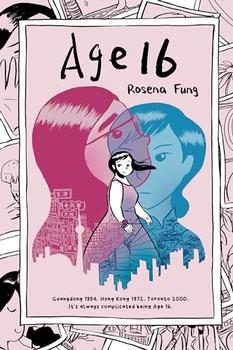

This article relates to Age 16

In Age 16 by Rosena Fung, we see body image issues play out across generations. Characters make disapproving comments about their daughters' bodies or encourage them to diet because they think they are being helpful. Lydia models diet culture for her daughter by criticizing her own body and openly counting calories.

In Age 16 by Rosena Fung, we see body image issues play out across generations. Characters make disapproving comments about their daughters' bodies or encourage them to diet because they think they are being helpful. Lydia models diet culture for her daughter by criticizing her own body and openly counting calories.

As is apparent in the novel's depiction of these issues in multiple eras and settings, from Guangdong to Hong Kong to Toronto, body dissatisfaction can exist across cultures. However, research shows it is especially persistent in wealthy countries with a more consumption-focused lifestyle. A study found that African immigrants to Europe took a more negative view of their bodies than Africans in Africa did. In Western countries, women who aren't white may feel more pressure to meet the Western beauty ideal in other ways, like through low body weight. Stress and discrimination can also trigger eating disorders for ethnic minorities in majority-white countries, and they may face barriers in getting help. Eating disorder rates in American women of Asian descent may be as high or higher than in white women, but they are less likely to be referred for treatment.

Studies also suggest that body image struggles are heritable, and the way mothers feel about their own bodies can have a big impact on their daughters. Very few mothers want their daughters to feel bad about their bodies, of course. But their response to the societal pressure to be thin can impact the next generation.

One study of five-year-old girls found that children whose mothers dieted were more likely to believe in a connection between dieting and body size. Children whose mothers diet are also more likely to go on to diet themselves. And mothers who speak negatively about heavier people are likely to pass on these attitudes to their daughters.

As Dr. Leslie Sim, clinical director of the Mayo Clinic's eating disorders program, tells USA Today: "Even if a mom says to the daughter, 'You look so beautiful, but I'm so fat,' it can be detrimental."

So what is a well-intentioned mother to do? How can a woman dealing with her own body image issues raise a daughter free of the same trauma?

Psychologist Sabrina Romanoff tells Forbes that being "kind and forgiving to your own body" is the "single best thing parents can do" to improve their child's body confidence.

Experts suggest that practices that most benefit daughters are beneficial to the mother as well. For instance, banishing negative self-talk and learning to practice self-compassion can help women raise daughters who are more confident in their bodies — while also improving their own self-image. A more varied media intake — consuming images and stories featuring people of all sizes — also benefits mothers and daughters alike. For some women, unlearning diet culture and fatphobia might take serious work, and may require the help of a professional therapist. The good news is that by becoming more body confident, mothers can help their daughters to do the same.

Woman feeding child

Photo by Tanaphong Toochinda via Unsplash

Filed under Society and Politics

![]() This article relates to Age 16.

It first ran in the July 31, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Age 16.

It first ran in the July 31, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

The good writer, the great writer, has what I have called the three S's: The power to see, to sense, and to say. ...

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.