Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

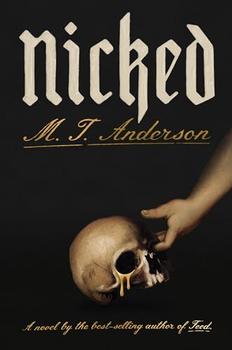

A Novel

by M.T. AndersonThis article relates to Nicked

M.T. Anderson's novel Nicked is based on a real-life relic theft occuring when, in 1087, an expedition from Bari, Italy, traveled to Myra, in present-day Turkey, to steal the bones of St. Nicholas. Even today, St. Nicholas's primary reliquary can be found in Bari, where pilgrims can buy holy water infused with the "myrrh" his bones supposedly produce. This heist, while entertaining enough to be the stuff of fiction, is but one of dozens of examples of relic theft throughout history, a phenomenon known as "furta sacra."

M.T. Anderson's novel Nicked is based on a real-life relic theft occuring when, in 1087, an expedition from Bari, Italy, traveled to Myra, in present-day Turkey, to steal the bones of St. Nicholas. Even today, St. Nicholas's primary reliquary can be found in Bari, where pilgrims can buy holy water infused with the "myrrh" his bones supposedly produce. This heist, while entertaining enough to be the stuff of fiction, is but one of dozens of examples of relic theft throughout history, a phenomenon known as "furta sacra."

In his book by the same name, historian Patrick J. Geary cites more than one hundred documented thefts during the period from roughly the ninth to the twelfth centuries. It's no wonder that there was a brisk business in relic sale, trade, and theft—Charlemagne himself dictated that every church altar in his empire should have a relic.

It wasn't just a legal mandate that drove this phenomenon, however; Geary outlines how, in medieval times, monasteries and other holy sites often relied on relics—and the pilgrims who would pay to visit these shrines—for their livelihood: "Possession of the remains of a popular saint could mean the difference between a monastery's oblivion and survival." What's more, Geary writes, "the only means of acquisition were purchase, gift, invention, or theft." In short, if a monastery couldn't afford to buy significant relics outright and weren't unethical enough to lie about false relics, they would resort to theft, often with the support of their entire community, who would all benefit by extension if a particularly notable saint's body (or parts thereof) could be acquired and displayed.

Church and civic leaders employed a variety of rationalizations to justify the theft of relics, including the argument that they were simply relocating a relic from a place where it was less venerated to a new home where it would be truly appreciated. Others made the claim that if a relic found its way to a new location, only the saint's will would have allowed it to be so.

Sometimes monks took it upon themselves to steal relics—one story tells of a French monk from Conques who spent ten years undercover at another monastery in Agen, waiting for the opportunity to steal the remains of St. Foy. Others seem to have undertaken this work professionally, such as a relic hunter known as Deusdona, who raided the Roman catacombs and then traded away supposed bits of saints' bodies for profit, since Catholic doctrine held that every part of a saint's body, no matter how small, was a site of holiness. The most hazardous aspect of Deusdona's business—which he ran with his brothers Lunisius and Theodorus—was probably transporting relics from southern Europe across the Alps to northern churches and monasteries.

Although the market for relics cooled during the Crusades—when religious fervor found new targets—and further still during the Reformation, when reformers like Martin Luther based part of their critique of the Catholic Church on its materialism, the phenomenon of relic theft is not unknown even today. As of 1969, the Catholic Church no longer requires relics to be housed in every altar, but many churches are still in possession of these sacred objects. Just this year, a fragment of bone smaller than a fingernail, purported to belong to Mary Magdalene, was stolen from a church in Salt Lake City. The church is offering a $1,000 reward—perhaps an incentive for a modern-day relic hunter to retrieve it and reap the treasure.

Abbey-church in Conques, France where the remains of Saint Foy were held after being stolen from Agen

2005 photo by Phillip Capper (CC BY 2.0)

Filed under Cultural Curiosities

![]() This article relates to Nicked.

It first ran in the July 31, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Nicked.

It first ran in the July 31, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Heaven has no rage like love to hatred turned, Nor hell a fury like a woman scorned.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.