Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

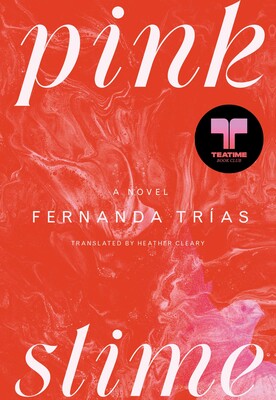

This article relates to Pink Slime

Fernanda Trías's Pink Slime takes its title from the nickname of Meatrite, a fictional meat paste developed by the government to combat food shortages during an environmental collapse. Although set in an imagined near future, Trías's Meatrite could easily be inspired by the ultra-processed foods (UPFs) that have come to dominate the 21st-century diet. Once seen as a way to cheaply feed a growing population, UPFs are now linked to an increasing number of chronic conditions, such as asthma and type 2 diabetes.

Fernanda Trías's Pink Slime takes its title from the nickname of Meatrite, a fictional meat paste developed by the government to combat food shortages during an environmental collapse. Although set in an imagined near future, Trías's Meatrite could easily be inspired by the ultra-processed foods (UPFs) that have come to dominate the 21st-century diet. Once seen as a way to cheaply feed a growing population, UPFs are now linked to an increasing number of chronic conditions, such as asthma and type 2 diabetes.

The roots of UPFs can be traced back to the Great Depression and Second World War, when circumstances dictated populations be fed as cheaply and efficiently as possible. Highly processed products like Spam—inexpensive, easily transportable, and ready to eat out of the can—became ubiquitous among Allied servicemen. Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev once even credited the product with saving the Russian army during the war.

Similar products like Swanson TV dinners and Cheez Whiz started becoming more prominent in the consumer market after 1945, but it wasn't until the 1980s that an explosion of convenience snacks and drinks popularized the term "ultra-processed foods." For several decades, however, the designation had no scientific basis or definition. Only in the early 21st century did Brazilian scientist Carlos Monteiro and his colleagues at the University of São Paulo propose what they called the Nova classification, a way of scientifically defining and categorizing the level of processing undergone by products. "Nova Group 4: Ultra-Processed Foods" cemented the term in scientific discourse and gave it a definition: "industrial formulations made entirely or mostly from substances extracted from foods, derived from food constituents, or synthesized in laboratories."

Since the definition of the term, scientists have been able to map out the extent to which UPFs have entered our food supply. The results are shocking. Recent studies show that UPFs make up more than 50% of the average American's energy intake. Similar research in the UK has found the same is true of the British diet.

Although the health effects of processed foods were causing alarm among some doctors almost immediately after the Second World War, UPFs have only recently captured the public's attention as a genuine health concern. (As the author Alan C. Logan writes, "The term 'ultra-processed food' is having a cultural moment.") Early in 2024, a review of existing data by the British Medical Journal found a direct association between exposure to UPFs and 32 different health outcomes—ranging from cancer to respiratory and cardiovascular conditions to anxiety and depression. Monteiro has called on advertisements for UPFs to be banned or heavily restricted and for packaging to feature warning labels similar to those found on cigarette packets. His recommendations may seem excessive, but the damage being wrought may be extensive. UPFs have been linked to heart disease, now the leading cause of death in America, along with many other conditions.

While much is still unclear about the exact reasons behind the associations between UPFs and poor health, there's evidence that what we're eating may be harming us—even killing us.

Hot dogs on buns

Photo by Polina Tankilevitch, via Pexels

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This article relates to Pink Slime.

It first ran in the August 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Pink Slime.

It first ran in the August 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Every good journalist has a novel in him - which is an excellent place for it.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.