Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Biography of Brain Surgery

by Theodore H. SchwartzThis article relates to Gray Matters

In Theodore H. Schwartz's book, Gray Matters: A Biography of Brain Surgery, the author traces the history of neurosurgery. His account begins with the work of Dr. Harvey Cushing, whom he calls the "undisputed founding father of neurosurgery," in the late 19th/early 20th centuries. If one considers any deliberate operation on the brain to be "brain surgery," however, the art has actually been around for millennia.

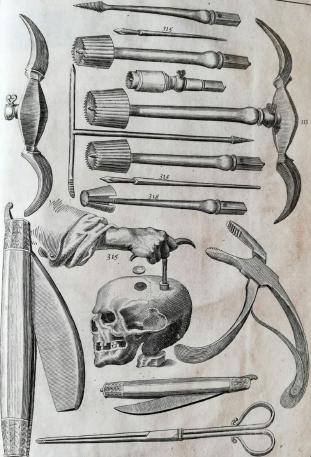

Trepanation—the act of creating a hole in the skull for medical reasons—is considered one of the world's most ancient surgical techniques. It's been practiced since at least the Neolithic period (beginning 10,000 BCE) and fossil evidence of its use has been found in Europe, South America, Africa, and Asia. In many cases trepanation was used to alleviate brain swelling and a buildup of fluid inside the skull, but evidence suggests it may also have been employed to cure cases of epilepsy, chronic migraine, and mental illness.

The technique used to create the hole and remove the piece of the skull without damaging the dura mater (the brain's covering membrane) varied from place to place and from century to century, but generally five different methods have been observed:

The technique used to create the hole and remove the piece of the skull without damaging the dura mater (the brain's covering membrane) varied from place to place and from century to century, but generally five different methods have been observed:

While trepanned skulls have been found in many places, two collections in particular have shed significant light on the ancient practice. A burial site in Ensisheim, France that dates from 6500 BCE contained 120 bodies, the skulls of 40 of which showed signs of trepanation. These had round holes in them that appeared to have been created by scraping with a sharp stone (as in the first method above). The gravesite also contained disks of skull the same size as the holes, some with a small hole punched in them, perhaps so they could be worn as an amulet. Many of the skulls showed signs of healing, meaning the patient survived the procedure, and very few of the apertures appeared to have been caused by trauma (i.e., the holes were deliberately made).

The other collection was part of an in-depth study conducted by David Kushner, a neurologist at the University of Miami in Florida; John Verano, a bioarchaeologist at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana; and Anne Titelbaum, a bioarchaeologist at the University of Arizona in Phoenix. As reported in a 2018 issue of the journal Science, they collected over 600 Peruvian skulls that showed signs of trepanation and divided them into categories by approximate archeological age. One of the more interesting findings was the improvement in survival rates and in the techniques used on the subjects. Among the earliest group, who lived from 400 BCE to 200 BCE, just 40% survived the procedure, while by the latest period studied, 1400-1500 CE, the survival rate had risen to 75-83%—a remarkable achievement by any measurement (in the American Civil War it was just 50%). In addition, the team found that the holes became smaller and cleaner over time. There was less drilling in general, and more "grooving"—a technique that helped reduce the risk of puncturing the dura mater.

Trepanation was widely used until the 19th century, when it was replaced by the craniotomy, the first of which was performed in 1889 by Dr. Wilhelm Wagner. Unlike trepanation, the craniotomy replaces the piece of removed skull once the brain's swelling has gone down. Today the procedure is considered a relatively safe one, using advanced imaging, specialized tools, and, perhaps most importantly, anesthetic.

Filed under Medicine, Science and Tech

![]() This article relates to Gray Matters.

It first ran in the August 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Gray Matters.

It first ran in the August 21, 2024

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.