Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

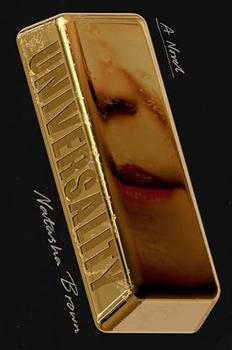

A Novel

by Natasha BrownThis article relates to Universality

In 1963, Jimmy Breslin chronicled the death of John F. Kennedy from the point of view of the man who dug his grave. Instead of joining the big names in journalism in awaiting statements of grief from world leaders, he went to the cemetery where the US president was to be buried in order to write "It's an Honor," a piece that told the story of America's reaction to the assassination from the perspective of the "common man." Breslin found a unique way to look at and narrate the events of the president's death that separated him from his journalist peers. Universality, the second novel by British author Natasha Brown, begins with a lengthy account of the attempted assassination of an anarchist leader on a farm in the English countryside. The author gives voice to a banker, a journalist, and a group of anarchists, but really tells the story of the deterioration of British society. Like Breslin, she finds another way to approach reality.

In 1963, Jimmy Breslin chronicled the death of John F. Kennedy from the point of view of the man who dug his grave. Instead of joining the big names in journalism in awaiting statements of grief from world leaders, he went to the cemetery where the US president was to be buried in order to write "It's an Honor," a piece that told the story of America's reaction to the assassination from the perspective of the "common man." Breslin found a unique way to look at and narrate the events of the president's death that separated him from his journalist peers. Universality, the second novel by British author Natasha Brown, begins with a lengthy account of the attempted assassination of an anarchist leader on a farm in the English countryside. The author gives voice to a banker, a journalist, and a group of anarchists, but really tells the story of the deterioration of British society. Like Breslin, she finds another way to approach reality.

"I'd been reading a lot about new journalism, and how Tom Wolfe and his contemporaries started taking from novelistic techniques and bringing those into journalism," explains Brown in an interview with Elle. Her goal in Universality was to examine how fact and fiction intertwine and blur.

Although there is no date that marks the birth of New Journalism, an era of formal experimentation in journalism began in the US in the 1960s. At that time, "one was aware only that there was some sort of new artistic excitement in journalism," as Tom Wolfe, one of the pioneers of this genre, wrote. Although Wolfe did not invent the term "New Journalism" (he did not even like it), he became one of the genre's greatest theorists. In 1972 he published in New York magazine "The Birth of 'The New Journalism'; Eyewitness Report," an extensive essay that would later become the first chapter of his book The New Journalism (1973), which was both a manifesto and an anthology featuring the most representative works of the genre.

In his essay, Wolfe explained how in the 1960s he made a discovery while reading his contemporaries: "that it just might be possible to write journalism that would ... read like a novel." According to him, New Journalism displaced the traditional novel, which he considered decadent, and became the richest literary form of the time.

New Journalism went beyond the inverted pyramid model, which was limited to answering the basic questions of traditional journalism (what, who, when, where, and why). It was a reaction to a context of profound social changes, a search for new expressive forms to break out of the conventional molds, and an attempt to satisfy the growing demand for explanations and more human and personal stories.

These journalists experimented with language and structure, daring to include dialogue, psychological study, varied characters, and descriptions of scenes. In Wolfe's words, "it was possible in non-fiction, in journalism, to use any literary device, from the traditional dialogisms of the essay to stream-of-consciousness, and to use many different kinds simultaneously, or within a relatively short space ... to excite the reader both intellectually and emotionally."

Magazines such as Esquire and New York were among the first to publish New Journalism pieces, and among the pioneers and most prominent exponents were Gay Talese, Joan Didion, Robert Christgau, Alma Guillermoprieto, Truman Capote, Norman Mailer, Hunter S. Thompson, and Rex Reed, many of them present in Wolfe's anthology.

However, these authors also generated debate about the extent to which a journalistic text could resemble a novel without compromising truth and fact. As an article in Britannica points out, by breaking the barrier between information and opinion, these journalists replaced "objectivity with a dangerous subjectivity that threatened to undermine the credibility of all journalism."

One of the most notable examples is Truman Capote's In Cold Blood, a "nonfiction novel" in which the author recounts the murder of a family on a Kansas farm. This work was as celebrated as it was controversial: in his five years of investigation, Capote became deeply involved with the two killers and was accused of manufacturing scenes and dialogues to better suit the story, further blurring the line between objective narrative and subjectivity.

In an interview with The Bookseller, Natasha Brown notes that "this kind of storytelling has taken on a new life on the internet." She cites as an example "Cat Person," Kristen Roupenian's modern-day dating short story published by The New Yorker that went viral and was mistaken by some readers for journalism. Brown remarked to Elle, "I thought that was really interesting. I thought, "What if I took a piece in journalistic style inside a novel, could it fit?'"

In Universality, the British author takes the tradition of New Journalism a step further, exploring not only the intersection between fiction and reality, but also the impact of storytelling on the public's perception of events. Like the pioneers of New Journalism, her work suggests that the way we tell a story can be as influential as the events themselves.

1973 edition of The New Journalism by Tom Wolfe, courtesy of Harper and Row

Filed under Books and Authors

![]() This article relates to Universality.

It first ran in the March 12, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to Universality.

It first ran in the March 12, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

I have always imagined that paradise will be a kind of library

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.