Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Camilla BarnesThis article relates to The Usual Desire to Kill

In 1951, Time magazine described the youth of the era in the following terms: "The most startling fact about the younger generation is its silence. With some rare exceptions, youth is nowhere near the rostrum. By comparison with the Flaming Youth of their fathers & mothers, today's younger generation is a still, small flame. It does not issue manifestoes, make speeches or carry posters." This explains why the generation born between 1928 and 1945 came to be known as the Silent Generation, an age cohort characterized by their strong sense of conformism and their traditionalism (another common term for this group is the Traditionalist Generation).

In 1951, Time magazine described the youth of the era in the following terms: "The most startling fact about the younger generation is its silence. With some rare exceptions, youth is nowhere near the rostrum. By comparison with the Flaming Youth of their fathers & mothers, today's younger generation is a still, small flame. It does not issue manifestoes, make speeches or carry posters." This explains why the generation born between 1928 and 1945 came to be known as the Silent Generation, an age cohort characterized by their strong sense of conformism and their traditionalism (another common term for this group is the Traditionalist Generation).

This generation is prominently represented in Camilla Barnes' The Usual Desire to Kill through the characters of the parents, Peter and his wife, who remains anonymous throughout, a choice that underscores her "silence." In a significant passage, she writes: "Who am I ... What part do I play? I have had no name but Mum for fifty years. Mum. I have just looked it up in Chambers Dictionary: 'Mum, adj. silent.— n. silence— interj. not a word.— v.t. to act in a dumb show.' Well, that about sums it up, doesn't it?"

Throughout the novel, we read the letters she sends to someone named "Kitty" in the 1960s, in which she recounts her time at Oxford studying literature, meeting Peter, becoming pregnant, and eventually accepting marriage as the natural course of action: "Well then. We had better get married" is Peter's response to the news. There is no rebellion, no questioning—just quiet acceptance, mirroring the generational attitude of taking life as it comes without resistance.

Both Peter and his wife embody the defining characteristics of those born during the interwar and World War II years. Peter, born in London in 1941, "could just about claim to remember the Blitz." His wife, born just after the war, laments having missed out on any defining historical moments: "She had been bequeathed the dullest bits—rebuilding, rationing, the grayness of the fifties. England had been left a smaller, poorer, grimmer place, an Empire on the decline."

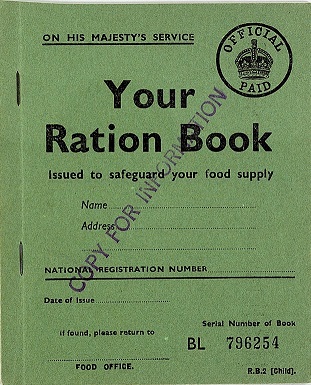

The effects of wartime scarcity are deeply ingrained in their behaviour. In her letters, ration cards are mentioned. At the time, scarcity translated into rationing, and rationing later translated into thriftiness: hoarding became a defining trait of the Silent Generation, who, shaped by an upbringing marked by economic depression, tend to accumulate things with the goal of not being wasteful. The novel humorously illustrates this tendency through the parents' attachment to a broken-down freezer they transported from Oxford to France. Even after it no longer fully closed, they kept it for 20 years. When their daughters gift them a new one, it is not met with enthusiasm: "The morning conversation was about the new freezer (Boswell was much better, etc. etc.; you know the story...) and how wasteful the two of us are. ('It wasn't like that during the war; we never had sweets, or bananas or chocolate. It was jam yesterday, jam tomorrow, but never jam today')."

Reflecting on her grandparents' generation, Alice, their granddaughter, observes: "They had turned having to 'go without' into an art and they were destined to hoard all their life. They hoarded not only the present (anyone who stepped inside the larder would see that) but also the past with newspapers, photos, Christmas cards all kept, as well as more anonymous items such as old tennis balls, empty tobacco tins, and a large collection of floppy disks from the eighties."

While Alice has a smooth relationship with her grandparents, the same cannot be said for the daughters of Peter and his wife, Miranda and Charlotte. Their strained dynamic is rooted in the strict, emotionally distant upbringing typical of the Silent Generation: "Dad said, 'Children should be seen and not heard.' But what he really meant was 'not seen and not heard,'" Miranda reflects.

As members of Generation X (born between 1965 and 1980), Miranda and Charlotte adopt a less rigid approach in raising their own children, embodying a shift in parenting philosophies. This generational divide is part of the broader phenomenon known as a "generation gap," a term which emerged in the 1960s and 1970s to describe how Baby Boomers, and then Gen X, rejected many of their parents' values and beliefs.

Of course, people do not always adhere to the specific characteristics common to their generation, and these characteristics may vary based on geographical, socioeconomic, and other circumstances.

The Usual Desire to Kill is a novel about generational conflict. It sheds light on a frequently overlooked generation and examines how their characteristics shaped not only their own lives, but also their relationships with the generations that followed.

Child's ration book from World War II, courtesy of the UK National Archives on Flickr

Filed under People, Eras & Events

![]() This article relates to The Usual Desire to Kill.

It first ran in the April 9, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

This article relates to The Usual Desire to Kill.

It first ran in the April 9, 2025

issue of BookBrowse Recommends.

Sometimes I think we're alone. Sometimes I think we're not. In either case, the thought is staggering.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.