Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

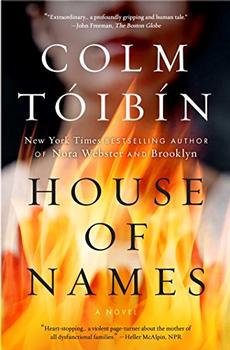

This article relates to House of Names

The story of Clytemnestra is told in bits and pieces across several play cycles from the Classical period, and before. At the end of the House of Names, the author Colm Tóibín notes that, while the majority of the novel's events are not related to any source material, the overall shape of the narrative and the main characters are taken from The Oresteia by Aeschylus, Electra by Sophocles, Euripides' Electra, Orestes, and Iphigenia at Aulis. Clytemnestra, as well as Electra, make appearances in other plays and art forms throughout history, but are rarely humanized in the way that we see in Tóibín's book. In fact, the way in which House of Names is perhaps most subversive is how Tóibín humanizes these characters who have largely been understood to be villains in ancient Greek society.

The story of Clytemnestra is told in bits and pieces across several play cycles from the Classical period, and before. At the end of the House of Names, the author Colm Tóibín notes that, while the majority of the novel's events are not related to any source material, the overall shape of the narrative and the main characters are taken from The Oresteia by Aeschylus, Electra by Sophocles, Euripides' Electra, Orestes, and Iphigenia at Aulis. Clytemnestra, as well as Electra, make appearances in other plays and art forms throughout history, but are rarely humanized in the way that we see in Tóibín's book. In fact, the way in which House of Names is perhaps most subversive is how Tóibín humanizes these characters who have largely been understood to be villains in ancient Greek society.

As in many other cultures at many points of history, women in ancient Greece, especially ancient Athens, were meant to be decorative, demur, and silent in society where they would defer to the power and mastery of men. Greek epics and drama reflect this; not only are the most important relationships between men, but also women who are seen as too strong or having their own mind or will are vilified. For the balance of power or "harmony" to be restored at the end of the play or story, such a woman must be punished. While there is no agreement with what Helen of Troy's fate was after the end of the war – Death? Reunited with her husband? At the mercy of those whose husbands and sons died because of her? – Clytemnestra, her half-sister, is painted as cunning and vindictive for plotting to avenge her daughter's death at the hands of her husband. Instead of bowing to her husband's will and his pursuit of victory, she acts as a warrior and exacts her revenge. Another woman who bucks the status quo and breaks out of the women's sphere is Medea, who, in the eponymous play by Euripides, not only chooses her own husband, but later avenges her marriage after her husband's infidelity by murdering her children.

As in many other cultures at many points of history, women in ancient Greece, especially ancient Athens, were meant to be decorative, demur, and silent in society where they would defer to the power and mastery of men. Greek epics and drama reflect this; not only are the most important relationships between men, but also women who are seen as too strong or having their own mind or will are vilified. For the balance of power or "harmony" to be restored at the end of the play or story, such a woman must be punished. While there is no agreement with what Helen of Troy's fate was after the end of the war – Death? Reunited with her husband? At the mercy of those whose husbands and sons died because of her? – Clytemnestra, her half-sister, is painted as cunning and vindictive for plotting to avenge her daughter's death at the hands of her husband. Instead of bowing to her husband's will and his pursuit of victory, she acts as a warrior and exacts her revenge. Another woman who bucks the status quo and breaks out of the women's sphere is Medea, who, in the eponymous play by Euripides, not only chooses her own husband, but later avenges her marriage after her husband's infidelity by murdering her children.

The most interesting thing to see over the next few years will be whether or not this depiction of strong, villainous women will change, or if it will always serve as a warning to other women.

While many other examples exist across literature, Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth probably evokes the most similar sense of cruelty and cunning as Clytemnestra, though there is room for debate over which is worse: murdering in cold blood to avenge a family member, or murdering in cold blood to promote your husband. But like Clytemnestra before her, Lady Macbeth finds that the price of power is sanity; this, of course, was deliberate, a way to signal socially to those who might see or hear the play that women who try to take a man's place can not succeed. Female villains were often used as a warning to the reader - this is what you should not be - because it was not acceptable for a woman to exhibit traits that were traditionally aligned with men in particular cultures at particular times. While female villainy as an expression of power in a social space is now being explored both in literature and literary scholarship, Tóibín's work succeeds because he doesn't play upon archetypes of "strong woman," "good woman," "madwoman," or any other two-dimensional rendering. The motives of his characters are three dimensional; readers can empathize with their decisions, and even sympathize. As authors and scholars continue to explore this in literature, it will be interesting to see how the representation of the three-dimensional woman evolves: especially looking at whether women who seek power will be given their due as rounded human characters or remain cast as villains, and as a warning to women readers of how not to behave.

The most interesting thing to see over the next few years will be whether or not this depiction of strong, villainous women will change, or if it will always serve as a warning to other women.

While many other examples exist across literature, Shakespeare's Lady Macbeth probably evokes the most similar sense of cruelty and cunning as Clytemnestra, though there is room for debate over which is worse: murdering in cold blood to avenge a family member, or murdering in cold blood to promote your husband. But like Clytemnestra before her, Lady Macbeth finds that the price of power is sanity; this, of course, was deliberate, a way to signal socially to those who might see or hear the play that women who try to take a man's place can not succeed. Female villains were often used as a warning to the reader - this is what you should not be - because it was not acceptable for a woman to exhibit traits that were traditionally aligned with men in particular cultures at particular times. While female villainy as an expression of power in a social space is now being explored both in literature and literary scholarship, Tóibín's work succeeds because he doesn't play upon archetypes of "strong woman," "good woman," "madwoman," or any other two-dimensional rendering. The motives of his characters are three dimensional; readers can empathize with their decisions, and even sympathize. As authors and scholars continue to explore this in literature, it will be interesting to see how the representation of the three-dimensional woman evolves: especially looking at whether women who seek power will be given their due as rounded human characters or remain cast as villains, and as a warning to women readers of how not to behave.

Electra, by Frederic Leighton 1830-1896

Helen of Troy, by Evelyn de Morgan, 1855–1919

Clytemnestra, by John Collier, 1882

Filed under Reading Lists

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to House of Names. It originally ran in May 2017 and has been updated for the

March 2018 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to House of Names. It originally ran in May 2017 and has been updated for the

March 2018 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

The only real blind person at Christmas-time is he who has not Christmas in his heart.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.