Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the Book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

This article relates to Heart of Junk

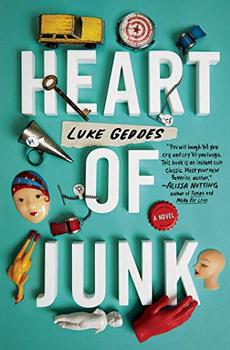

Heart of Junk, the debut novel from Luke Geddes, is set in the fictional Heart of America antique mall in Kansas. The vendors in the mall hope to make some money selling off bits of their collections—Barbies, postcards, glassware, furniture and more. Geddes uses each collection to tell the reader something about its owner, as well as to explore the concept of value in our personal belongings.

Heart of Junk, the debut novel from Luke Geddes, is set in the fictional Heart of America antique mall in Kansas. The vendors in the mall hope to make some money selling off bits of their collections—Barbies, postcards, glassware, furniture and more. Geddes uses each collection to tell the reader something about its owner, as well as to explore the concept of value in our personal belongings.

Over the past decade, American society has had a love/hate relationship with "junk." Collector-based television shows such as American Pickers and Pawn Stars, as well as the long-running Antiques Roadshow, have glamorized the colorful, strange and wondrous collections of people from all walks of life. On the other hand, shows like Hoarders shine a light on the perils of unchecked collecting as a potential sign of a mental health condition.

So how do collectors differ from those with hoarding disorder, a diagnosable mental illness?

Collecting is a common leisure activity for a large percentage of the population. Collectors, for the most part, limit their acquisitions to a specific area or type of item, and their collections are typically systematic and organized, with the items on display in such a way as to be shared with other interested individuals. The items in the collection tend to have some value, whether that value is monetary or sentimental, the latter of which may be subjective to the individual. Private art collections, for example, can go for many millions of dollars (David Bowie's personal art collection sold at auction for over $40 million after his death), while a collection of Beanie Babies has little value (with the exception of a few rare pieces) outside of its owner's memories of purchasing each plush. Collectors also tend to have a working knowledge of the history, rarity and worth of their pieces. Additionally, it's not unusual for collectors to trade, swap, or make deals with others in order to get rid of things they no longer want and/or get something new, and when a collector dies, they often bequeath their collection to a museum, an institution, or other collectors in order to preserve the proof of their dedication.

Hoarding is a form of extreme collecting with a mental health aspect. It was first classified as a diagnosable disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 2013. According to the American Psychiatric Institute, this disorder occurs in approximately 2-6% of the population and is more common in males and in older adults (55-94 years of age). A person with hoarding disorder has acquired and failed to discard a large number of possessions that seem to others to be useless or of limited value. These possessions clutter living spaces to the degree that they can't function for their intended use, potentially presenting a health and safety risk.

Furthermore, the thought of parting with their possessions will cause a hoarder significant distress, a symptom that can impair attempts to clean up their home. While hoarding does have some overlap with collecting—especially in individuals considered by psychiatrists to be extreme collectors—this is the key difference between the two. While collectors may be disinclined to part with certain pieces, they generally will not experience true distress when they do so, and they also usually expend a good deal of time and energy on the organization and upkeep of their collection.

More recently, scientific research on the subject of "stuff" has turned to Marie Kondo, a Japanese tidying expert, and her ideology of minimalism and decluttering. Known as the KonMari method, this technique is used to reorganize the home and get rid of clutter and mess by essentially paring down belongings to just what you need. This is done by keeping only the things that "spark joy," a concept that may work better for some than others, and, in the case of hoarders, may be problematic. While a hoarder's belongings might not necessarily bring joy, the thought of losing these belongings brings distress, and the difference is one of nuance. For the average user, however, the act of decluttering has been shown to have a number of positive outcomes. Studies have shown that messiness can negatively affect accuracy in tasks and lead to procrastination. Decluttering, meanwhile, has been shown to reduce anxiety and eliminate allergens and other bacteria that live on household items, improving both mental and physical health.

As American society has shifted to focus on stuff, our relationship with our belongings has become increasingly complex. On one extreme are hoarders, who can't help amassing large collections of things that can literally be trash, while on the other are people who embrace the Kondo method and promote possessing only the essentials. Most people, like the characters of Heart of Junk, fall somewhere in the middle. Despite being somewhat over-the-top—the book is a satire, after all—the dealers at The Heart of America show that the things we own can be valuable, even if that value is only personal. And like the dealers, our own collections can reveal a lot about us.

Marie Kondo, courtesy of KonMari

Filed under Society and Politics

![]() This "beyond the book article" relates to Heart of Junk. It originally ran in February 2020 and has been updated for the

January 2021 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

This "beyond the book article" relates to Heart of Junk. It originally ran in February 2020 and has been updated for the

January 2021 paperback edition.

Go to magazine.

Judge a man by his questions rather than by his answers.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.