Contents

Highlighting indicates debut books

Discussions are open to all members to read and post. Click to view the books currently being discussed.

Literary Fiction

Historical Fiction

Short Stories

Essays

Mysteries

Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Speculative, Alt. History

Biography/Memoir

History, Current Affairs and Religion

Science, Health and the Environment

True Crime

Literary Fiction

Thrillers

Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Speculative, Alt. History

Biography/Memoir

| BookBrowse: | |

| Critics: | |

| Readers: |

"A dark and heady dream of a book" (Alix E. Harrow) about a ruined mansion by the sea, the djinn that haunts it, and a curious girl who unearths the tragedy that happened there a hundred years previous

Akbar Manzil was once a grand estate off the coast of South Africa. Nearly a century later, it stands in ruins: an isolated boardinghouse for eclectic misfits, seeking solely to disappear into the mansion's dark corridors. Except for Sana. Unlike the others, she is curious and questioning and finds herself irresistibly drawn to the history of the mansion: To the eerie and forgotten East Wing, home to a clutter of broken and abandoned objects—and to the door at its end, locked for decades.

Behind the door is a bedroom frozen in time and a worn diary that whispers of a dark past: the long-forgotten story of a young woman named Meena, who died there tragically a hundred years ago. Watching Sana from the room's shadows is a besotted, grieving djinn, an invisible spirit who has haunted the mansion since her mysterious death. Obsessed with Meena's story, and unaware of the creature that follows her, Sana digs into the past like fingers into a wound, dredging up old and terrible secrets that will change the lives of everyone living and dead at Akbar Manzil. Sublime, heart-wrenching, and lyrically stunning, The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years is a haunting, a love story, and a mystery, all twined beautifully into one young girl's search for belonging.

Prologue

1932

In an old wardrobe a djinn sits weeping.

It whimpers and murmurs small words of complaint. It sucks its teeth and berates the heavens for its fate. It curses the day it ever entered this damned house. It closes its eyes and tries to imagine a time before it came here, before it followed the sound of stars from the shore, before the world turned dark and empty.

Something thuds somewhere and the djinn is drawn from its misery by a commotion happening outside. It stops to listen and sounds begin to emerge; doors bang, windows shut, and things are thrown about. There are shouts as orders are given and people hurry through passages. They run up and down and bump heavy things along the stairs.

The djinn pauses, then it uncurls its limbs, swings open the cupboard, and steps out.

There is the patter of footsteps, then the front door slams downstairs and everything is suddenly still.

The djinn steps into the passage and looks around curiously. The floor is scattered with clothing and bedding. It wanders into the rooms; in a child's bedroom, next to a smoking fireplace, twenty-seven plastic soldiers wait for a French army to advance. In a woman's bedroom, a silk camisole slips off a swinging hanger in a closet.

The djinn creeps downstairs. In the kitchen, a dish of potatoes soaks beneath a dripping tap. Steam rises from a set-aside kettle. A basket of fresh laundry waits to be ironed.

The djinn wanders into the long dining room, among the high-backed chairs, and peers into the entrance hall where a grandfather clock ticks loudly. It pulls open the heavy front doors and looks into the bright, clear light of early morning. The stone stairs are strewn with opened trunks and scattered books. The driveway lies empty. The djinn steps outside into the pale pink light and looks to the still, shimmering ocean.

It turns to the looming house behind and wails.

One

2014

No one in Durban remembers a Christmas as hot as this.

The heat is a living breathing thing that climbs through windows and creeps into kitchens. It follows people to work and at queues in the bank and on trains home. It crouches in bedrooms, growing restless until at night in fury it throttles those sleeping, leaving them gasping for breath. It sweeps through the streets and bursts open pipes, smashes open green guavas, and splits apart driveways. It burns off fingerprints and scorches hair and makes people forget what they are doing and where they are going so that they wander around beating their heads.

At the taxi rank in town people wave newspapers under their arms and wipe their foreheads with pamphlets that promise to bring back lost lovers. Witch doctors' phone numbers drip down their temples and into their pockets in inky-blue puddles. Bananas blacken in the sun on pavement tables. The humidity grows and strangers are drawn to one another without meaning to and they cling together in a sweaty unhappy mess.

Out in the suburbs people sit in their inflatable pools with party hats and sip cheap wine from plastic cups. They eat bunches of litchis and hunks of watermelon and burn meat black on the braai. Maidless madams push hair out of their eyes as they hang up washing and count down to the end of the holidays. Dirty dishes pile up in sinks, garbage bags burst open with maggots.

At the coast the sky opens wide and burns the sea white. Little children in multicolored swimsuits skip across the hot sand and shriek in thrilled agony. Families with pots of biryani and lukewarm Coke sit under small umbrellas fanning themselves with Tupperware lids as they dish rice onto paper plates.

The pier stretches on to eternity like a foreboding finger.

Sana Malek winds down her window and searches for a breeze. The dark curtain of hair flies off her neck to reveal her mother's chin, and she turns this way and that as she struggles to make it her own. She is neither girl nor woman, hovering in that space between the two, where at the edge of her thoughts, curling at the eaves, is the ...

Excerpted from The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years by Shubnum Khan. Copyright © 2024 by Shubnum Khan. Excerpted by permission of Viking. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

Unless otherwise stated, this discussion guide is reprinted with the permission of Penguin Books. Any page references refer to a USA edition of the book, usually the trade paperback version, and may vary in other editions.

Shubnum Khan's eloquent and moving debut novel opens in 1932, when a djinn that haunts a house by the sea is in mourning following an unexplained violent event, at once engaging the reader and setting the stage for an intriguing mystery to be unraveled. We then fast-forward to Durban, South Africa, in 2014, during the hottest Christmas anyone can remember. Fifteen-year-old Sana Malek moves with her father, Bilal, to a crumbling house called Akbar Manzil, a once-grand mansion that lay abandoned for years before being converted into apartments. We learn that Sana's mother died four years earlier and Bilal, still grieving, is eager to make a fresh start for himself and his daughter.

However, there is something eerie about the house that cannot be attributed to the frequent power failures, unreliable water supply, and rising damp. Previous tenants have moved in and out, complaining that the house is "not right"; indeed, that it is somehow alive and "watching." Those who remain when Sana and Bilal move in are an assortment of eccentric characters and lost souls of the South African Indian Muslim community, including the elderly landlord, known as Doctor. All are caught up in tangled webs of their own memories and misfortunes, as the house — and something in the house — watches furtively, silent witness to a forgotten grief.

The quiet, introverted Sana immediately becomes attuned to the house, sensing a shadow that lurks within. She hears it scuttle across the floor, perceives it in the corner of her eye, sees it lunge from the darkness and retreat before the light. In her exploration of the decaying rooms, Sana finds discarded items — old photographs, broken toys, and, eventually, a journal. Little by little, she begins to piece together the shards of the shattered family who once lived there, as the djinn watches, aggrieved, anguished, and bitter.

Hauntings are at the heart of this beautifully written and constructed novel. Both Akbar Manzil and Sana are haunted: the house by the djinn who loved and lost, and Sana by another ghost; though Sana's supernatural encounters are depicted in so skillful and ambiguous a way that her haunting could be real, or just as easily a product of her own imagination and guilt. Her uncovering of the past tragedy is mirrored by her gradual coming to terms with her own family's tragic history. "So, are ghosts real?" Doctor asks Sana, after confiding that he sometimes thinks his late wife is with him. "I think ghosts are as real as we make them."

The author powerfully evokes the contrasting worlds of a glamorous 1930s Muslim Indian family who emigrate to South Africa and the 21st-century diaspora. Gloriously infused with the colors, fragrances, sounds, landscapes, and, especially, cooking, of Indian South Africa, the novel brings history, culture, and contemporary society to vivid and wondrous life. Mouth-watering descriptions of food and aromas serve to show the culinary arts as a source of comfort and healing. Bilal copes with the loss of his wife through cooking, an activity that numbs the pain of her passing. Meals unite the disparate group of tenants as a cultural connection they all share, bringing joy to a household of sorrow.

A tantalizing slow burn at first, the plot is superbly paced. Tension builds as the book travels back and forth through time, unveiling events as Sana pieces together what she can of the mystery and heightening anticipation for further revelations. It comes full circle, as past and present merge and overlap, and reaches an incendiary yet ultimately cathartic denouement. An exquisite, lyrical, heart-rending tale of love and loss, estrangement and belonging; and an enthralling mystery spanning a century of history and heritage — just like the djinn itself, who waits a hundred years.

Reviewed by Jo-Anne Blanco

Alix E. Harrow, New York Times bestselling author of The Starling House

Alix E. Harrow, New York Times bestselling author of The Starling House

Yangsze Choo, New York Times bestselling author of The Night Tiger

Yangsze Choo, New York Times bestselling author of The Night Tiger

Rated 5 out of 5

by Gloria M

Unexpectedly Good!

The title of Shubnum Khan's latest novel, "The Djinn Waits A Hundred Years" made me stop and wonder just how quirky this tale would be? I am so happy my initial reaction did not prevent me from reading it! It is great!

Who does not love the epic and involved history of a huge and now deteriorating mansion? Throw in a plucky curious young girl trying to navigate her life without her mother and with her grief stricken dad and an assorted, diverse group of down on their luck co-residents and a djinn haunting the premises and this story sings!

Sana needs this mystery to distract her from the less than optimal conditions of her new home at he South African estate known as Akbar Manzil. (After her dad Bilal tries to reassure her by saying he thinks her mother would have liked this place, Sana muses "She would have hated this place. She would have said it was filthy and falling apart. She would have said he was out of his mind for coming here.")

Sana finds an old photo of a couple obviously in love and some discarded diaries in the east wing and starts researching the past. She also gets to know her neighbors, the elderly Doctor who runs the place and Razia Bibi- abandoned by her husband and rarely visited by her beloved son, and lonely Fancy who misses her daughter and tries to mediate all the conflicts within the building, Pinky- the staff member who fails hilariously at meeting her responsibilities and talks in the third person, and Zuileikha who has fled her renowned musical career and failed love affairs.

Khan keeps the narrative engaging and interesting, with flashbacks to the past and Sana's search for answers and closure. The djinn is around to provide important details and while the reader will soon be fairly certain of the fate of the female of the couple, the particulars will be well worth the wait. This book deserves a spot on your TBR!!! It will linger in your thoughts for quite some time!

In Shubnum Khan's debut novel The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years, set amidst the Indian diaspora of South Africa, fifteen-year-old Sana and her father move into a dilapidated house by the sea that is haunted by a djinn. The djinn is the link between past and present, a connection between the 21st-century tenants and the immigrant family who lived there in the early 1930s. This mythic spirit serves as a manifestation of the Islamic history and culture brought to South Africa by the Muslim Indian émigrés — an unseen witness to their past and present lives.

In Shubnum Khan's debut novel The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years, set amidst the Indian diaspora of South Africa, fifteen-year-old Sana and her father move into a dilapidated house by the sea that is haunted by a djinn. The djinn is the link between past and present, a connection between the 21st-century tenants and the immigrant family who lived there in the early 1930s. This mythic spirit serves as a manifestation of the Islamic history and culture brought to South Africa by the Muslim Indian émigrés — an unseen witness to their past and present lives.

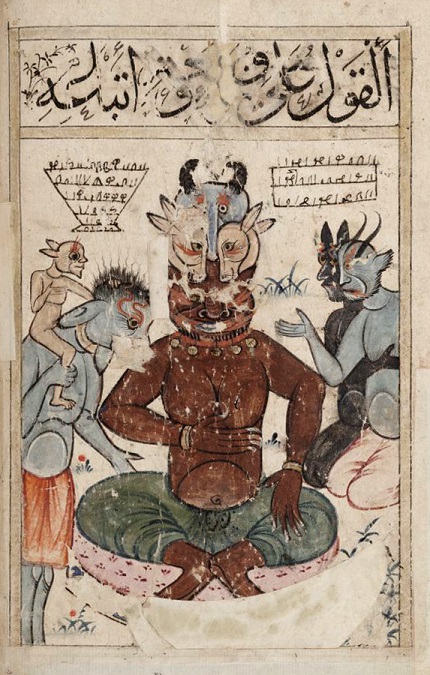

In her CrimeReads essay, "Decolonizing the Gothic," Khan writes of her family history and the stories told by her grandfather, who emigrated to South Africa in 1935. Among the most potent and vivid of the stories and legends her family brought with them from India are those of djinns (also spelled "jinn" or "jinni," and etymologically the origin of the English word "genie"). Djinns are a race of spirits in Islamic mythology who were created out of fire by Allah. They are shapeshifters who take on animal and human forms. They can make themselves invisible, see the future, possess bodies and inanimate objects, spread disease, and generally wreak havoc. In South Africa, djinns are also linked to curses and spells, and spirit healers are called upon to remove them. In the mortal world, they inhabit dark places such as caves, cemeteries, ruins or run-down buildings, again, like the djinn in Khan's novel.

Legends about djinns are found throughout Islamic folklore and literature, appearing in everything from the tales of the One Thousand and One Nights to Netflix and UNESCO's 2023 series of short films, African Folktales, Reimagined. Their origins date back to pre-Islamic Arabic pagan cultures. They were nature spirits who served to inspire poets, philosophers, and prophets by granting them glimpses of the supernatural world. As Islam spread west to Africa, the concept of the djinn was absorbed into the local communities' preexisting beliefs about the spirit world.

In Morocco, there are legends of djinns inhabiting trees; tree djinns are sympathetic to humans and will allow them to rest in the shade — though the fig tree must be avoided, as its djinn is mischievous and delights in inciting quarrels. According to a 2012 survey done by the Pew Research Center, 86% of Moroccans believe in the existence of djinns. The belief in djinns is also prevalent in Egypt: in 2021, The New Arab reported that in the Egyptian city of Qalyoub, local people's fear of a djinn residing at the bottom of a well in the 13th-century al-Zahir Baybar Mosque was causing worshippers to stay away. It was rumored the djinn was guarding hidden treasure in the well, but people were too afraid to go near it, and the authorities were urged to intervene and investigate. Other countries with high rates of belief in djinns among the Islamic population include Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Tunisia.

African folklore is replete with stories of djinns and their involvement with humans. Mousa-Gname, or Mousa-Djinni, is an epic hero of the Songhai people of West Africa, and the child of a human woman and tree-dwelling djinn. In the Saharan folk story, "The Tale of Tafaka," a young woman, Binta, sees a pregnant lizard ("tafaka") and offers to help it give birth. When Binta is summoned, she finds the lizard transformed into a beautiful female djinn and stays in the world of the djinns for 40 days, learning about their powers. After she returns, a young man appears looking for a bride, and Binta summons a beautiful female djinn to marry him. Thus djinns and humans are united, and this explains why the women of the Sahara region are all so beautiful. The Djinn Waits a Hundred Years is a worthy addition to this tradition of bringing together djinns and mortals.

Zawba'a, king of the djinns, depicted in a 14th-century manuscript called Kitab al-Bulhan courtesy of the University of Oxford's Bodleian Library

Filed under Places, Cultures & Identities

From the critically acclaimed, Booker Prize-nominated author of Sleeping on Jupiter and All the Lives We Never Lived, an incisive and moving novel about the struggle for creative achievement in a world consumed by growing fanaticism and political upheaval.

These intimate stories of South Indian immigrants and the families they left behind center women's lives and ask how women both claim and surrender power - a stunning debut collection from an O. Henry Prize winner.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.