Contents

Highlighting indicates debut books

Discussions are open to all members to read and post. Click to view the books currently being discussed.

Literary Fiction

Historical Fiction

Short Stories

Essays

Mysteries

Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Speculative, Alt. History

Biography/Memoir

History, Current Affairs and Religion

Science, Health and the Environment

True Crime

Literary Fiction

Thrillers

Fantasy, Sci-Fi, Speculative, Alt. History

Biography/Memoir

| BookBrowse: | |

| Critics: |

A riveting and elegant story of climate change on one city street, full of surprises and true stories of human struggle and dying local trees – all against the national backdrop of 2023's record heat domes and raging wildfires and, simultaneously, rising hopes for clean energy.

In 2023, author and activist Mike Tidwell decided to keep a record for a full year of the growing impacts of climate change on his one urban block right on the border with Washington, DC. A love letter to the magnificent oaks and other trees dying from record heat waves and bizarre rain, Tidwell's story depicts the neighborhood's battle to save the trees and combat climate change: The midwife who builds a geothermal energy system on the block, the Congressman who battles cancer and climate change at the same time, and the Chinese-American climate scientist who wants to bury billions of the world's dying trees to store their carbon and help stabilize the atmosphere.

The story goes beyond ailing trees as Tidwell chronicles people on his block coping with Lyme disease, a church with solar panels on its roof and floodwater in its basement, and young people anguishing over whether to have kids –all in the same neighborhood and all against the backdrop of 2023's record global temperatures and raging wildfires and hurricanes. Then there's Tidwell himself who explores the ethical and scientific questions surrounding the idea of "geoengineering" as a last-ditch way to save the world's trees – and human communities everywhere – by reflecting sunlight away from the planet.

No book has told the story of climate change this way: hyper-local, full of surprises, full of true stories of life and death in one neighborhood. The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue is a harrowing and hopeful proxy for every street in America and every place on Earth.

Introduction

The biggest trees on my street weren't yet sick and dying when I moved to the 7100 block of Willow Avenue in Takoma Park, Maryland. There were true giants back then, red and white oaks, tall and broad, offering a daydream greenery of good health. I was in good health, too. I was twenty-nine years old. I ran three miles per day. I grew native wildflowers in my backyard garden a few hundred feet from the border with Washington, DC.

But that was 1991, before the chaos of climate change really settled in over this narrow block of fourteen houses—and settled in over the world.

Thirty years ago, scientists and journalists had to travel to the Arctic or Australia's Great Barrier Reef to see the beginning impacts of global warming up close. Three decades later—after the dumping of nine hundred more gigatons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from oil, coal, and gas combustion—those impacts are everywhere. My neighborhood block, a microdot on any Google map, has shifted to a whole new universe. Maybe you see it where you live, too.

Those old oaks, casting muffled pools of overlapping shade, formed a durable ceiling of branches here in the 1990s and into the 2000s. Then came the years of heat, the weird rain, the beetles, and finally, starting in 2019, a sudden calamity. Today, tens of thousands of mature trees across Takoma Park and adjoining cities and counties survive only as mute tombstones, the chainsawed stumps of a region-wide graveyard of lost giants.

There were no deer thirty years ago on my block; now they roam everywhere, spreading Lyme disease from ticks that survive our milder winters. Neighbors show photos of those "old" winters, decades back, with bundled-up children atop sleds in the deep snow of lower Willow Avenue's steep hill. And past summers? Old newspapers show fewer overheated people and faces, it seems, at the Fourth of July parade. Now umbrellas are a common parade feature as the natural parasols of trees decline. My church, meanwhile, a block from my house, never experienced urgent water problems until the altered weather patterns of the last few years. Now there's an elevated flood berm on one side of the church—price tag $45,000—to keep water out of the basement preschool.

Every day, I think about this: If life is so different here, so scrambled in this old trolley suburb bordering America's capital city, where can anyone hide on this planet? At one point in my long personal battle with Lyme disease, picked up from a tick in my backyard, I couldn't read or write or understand someone speaking directly to me. But I have access to medicine and professional treatment. I can't imagine the lot of Senegalese villagers penniless and suffering through the latest round of climate-induced dengue fever. Or the paycheck-to-paycheck Louisiana shrimper, buffeted by bigger hurricanes and ruined by drowning wetlands.

There are still big trees on my block today—elder oaks, shrinking in number, nobly hanging on despite it all. But if they could, if those trees had legs, they would run away from this place, I think. They would head north, maybe three hundred miles, to western New York or southern Canada, to a latitude where at least the temperature is closer to what they were born into as acorns generations ago in my Maryland town. But that's just temperature. They'd still be prone to the more frequent storms and higher winds and altered insect patterns that are stressing out trees and killing them the world over. Even with legs, the old oaks on my block could not run away.

I did not become a climate activist years ago to save trees. I did it, first and foremost, to save the future of my son, Sasha, now twenty-seven. But the oaks on my street are a fair measurement of our collective progress on global warming. Wherever mature oak trees are found, in urban forests or wilderness settings, they are a keystone species, indicating ecological health. Beyond the bounty of acorns, they are ...

Excerpted from The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue by Mike Tidwell. Copyright © 2025 by Mike Tidwell. Excerpted by permission of St. Martin's Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

It starts with a murder mystery of sorts: what is killing the trees on a certain street in the Washington, DC suburb of Takoma Park, Maryland? The investigation sparks climate activist Mike Tidwell's obsession with spotting evidence of climate breakdown around his city. Along the way, he also discovers glimmers of hope, in the form of local scientists working on climate mitigation projects and residents coming together to make their neighborhood more resilient.

Tidwell, who moved to Takoma Park in 1991, has observed severe climatic changes in the intervening decades, including less snow, more storms, suffocating heat, and wetter summers. In general, the weather has become more unpredictable and extreme; nearby Ellicott City had two "one-thousand-year flood" events within two years (2016 and 2018). The deer population has also exploded, leading to more ticks surviving the newly mild winters and subsequently infecting humans. Tidwell is one of several in his neighborhood struggling with chronic Lyme disease after tick bites.

But the most visible effect of climate change on the author's street is the disappearance of many trees—between 2019 and 2021 alone, 1200 were lost across the city. Several of Tidwell's neighbors have had to order oak trees cut down, the giant stumps remaining as reminders of former majesty. These oaks had previously provided food and habitat for 500 species, as well as shade, beauty, and well-being for people—it's ten degrees cooler under a mature oak. Tidwell learns that, due to increasing rainfall, oak roots are being attacked by the water mold phytophthora. In response, ailing trees release a chemical distress signal that attracts ambrosia beetles, which drill into the trunk. By the time sawdust-lined holes in the bark appear, it's too late. Every dying tree requires complicated dismantling by skilled arborists. Every loss provokes grief.

The early chapters set the scene, while the rest of the book is a month-by-month picture of the state of the environment over the course of the year 2023, through the lens of Takoma Park. Many of Tidwell's neighbors are eco-conscious and have electric cars and solar panels. He vacillates between optimism about people's engagement and gloom as abnormal heat is followed by Canadian wildfire smoke. It's grimly appropriate that he embarks on this project not knowing that 2023 will go down in history as the planet's hottest year (at the time—2024 proved even hotter).

Curious about what actually happens to his city's dead trees, Tidwell teams up with neighbor Ning Zeng, a professor of climate science at the University of Maryland. Together they visit Camp Small, a sort of tree graveyard in Baltimore. The yardmaster tells them he only sells 15% of what comes in, as mulch or timber. He's inundated with trees, especially white oaks (the state tree of Maryland). Zeng's research focuses on burying dead trees in clay so they don't release their carbon into the atmosphere. One thread of the book follows up on his efforts to cut through red tape and find farmland where he can bury five thousand tons of timber.

Tidwell also surveys other climate mitigation strategies (see Beyond the Book) and meets with environmentally minded local politicians. His Maryland House of Delegates representative, Lorig Charkoudian, accompanies him to view a Virginia offshore windmill. In his own community, he gets involved in several grassroots projects. With Barbara, a Sierra Club activist, he goes hunting for methane leaks, which harm trees. Making the best of the resultant loss of shade from tree removal, he and his neighbor Dorothy create miniature roadside gardens to grow vegetables. Around the neighborhood, people plant new trees such as cypresses and swamp oaks that can cope with waterlogged conditions. He recalls the success of a 2021 volunteer campaign to cut down English ivy and other invasive vines choking trees.

The narrative is wide-ranging, covering many aspects of the climate crisis. With his journalistic eye for detail, Tidwell captures real people and scenes in an engaging way. At times, however, the content is overly technical. Moreover, climate science and policy are so fast-changing that in places—particularly since the January 2025 inauguration of the second Trump administration—the policies and approaches Tidwell discusses are out of date already.

Although the book's scope might initially seem overly provincial, the strategy of understanding global phenomena through a local microcosm is very effective. I had a personal reason for wanting to read this: I was born in Takoma Park. Although I've now lived in England for 20 years, I hear from my sister about Maryland's weather, such as the rise in tornadoes, which never happened when we were children. Wherever we live, all of us will have more examples of crazy weather, as former rarities become commonplace. It may be sobering to sit with the facts of climate breakdown while reading a book such as this, but knowledge empowers collective action.

Reviewed by Rebecca Foster

Bill McKibben, author The End of Nature

Bill McKibben, author The End of Nature

Daniel Sherrell, author Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World

Daniel Sherrell, author Warmth: Coming of Age at the End of Our World

In The Lost Trees of Willow Avenue, author Mike Tidwell offers an overview of strategies being researched and implemented to mitigate climate change. Overall, the main strategies are decarbonization and the drastic cutting of greenhouse gas emissions by switching from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Geoengineering technologies also aim to reverse the effects of climate change and remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. Here's a brief summary of a few specific approaches with the potential to slow the effects of climate change:

Solar Radiation Modification

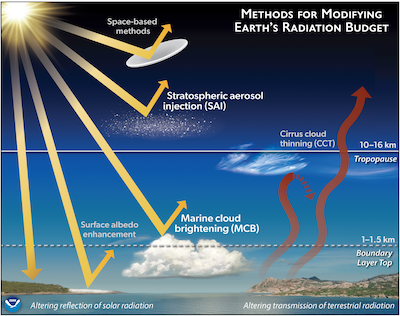

Solar radiation modification involves reflecting sunlight back into the atmosphere before it can reach the Earth and raise surface temperatures. This technology is modeled on the 1991 eruption of Mt. Pinatubo in the Philippines, whose sulfur emissions led to half a degree of cooling worldwide. Stratospheric aerosol injection mimics a volcanic eruption by releasing particulates or their precursors, such as sulfur dioxide, into the stratosphere (the second-lowest layer of the atmosphere). Marine cloud brightening (MCB) involves injecting aerosols such as sea salt into the lower atmosphere to increase the reflectivity of clouds over oceans. In the book, Tidwell meets a NASA scientist, Dr. Tianle Yuan, who is working on MCB. Other strategies include surface albedo enhancement (white roofs), cirrus cloud thinning, and the installation of giant mirrors in space to reflect sunlight before it enters the Earth's atmosphere.

Carbon Sequestration

In Tidwell's book, Ning Zeng's project of burying dead trees serves as a method of carbon sequestration. Trees are natural carbon sinks in that they absorb more carbon dioxide than they release. Wood vaults such as Zeng's form part of a broader umbrella of strategies for carbon dioxide removal (also including peatland restoration and reforestation). These strategies shift the goal from the reduction of emissions to the achievement of "negative emissions."

Regenerative Agriculture

Regenerative agriculture—as opposed to the business-as-usual practice of industrial agriculture—aims to restore soil health and improve biodiversity. This farming approach minimizes soil disturbance (the "no-till" practice reduces erosion, compaction, and the loss of soil moisture) and the use of artificial fertilizers or pesticides. It also involves rotating crops, and using cover crops during fallow periods, to maintain the soil's fertility and keep weeds and plant diseases under control. Soil can also be enhanced with biochar (a form of charcoal made by heating plant matter without oxygen) or a crushed silicate rock such as basalt.

Although it is encouraging that so many avenues are being explored, often the political will to fund scientific research does not exist. As citizens, we can get involved in small-scale community projects, but it is also important to pressure politicians into cooperating on global initiatives with broader effects.

Proposed methods for modifying Earth's radiation budget, including SRM methods and cirrus cloud thinning, courtesy of climate.gov

Filed under Nature and the Environment

The untold story of climate migration—the personal stories of those experiencing displacement, the portraits of communities being torn apart by disaster, and the implications for all of us as we confront a changing future.

We still have time to change the world. From Greta Thunberg, the world's leading climate activist, comes the essential handbook for making it happen.

Books with similar themes

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.