Summary | Excerpt | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

An Inspector Chen novel

by Qiu XiaolongThis is the fourth volume in Xiaolong's

Inspector Chen series, but it is not necessary to have read the

earlier books to appreciate this one. The series, set

mainly in 1990s Shanghai (although about half the action in A

Tale of Two Cities takes place in Los Angeles), explores the

fast changing political and cultural climate of modern China

through the eyes of Inspector Chen who, like the author, came

across an English textbook as a teenager, which triggered a

lifelong interest in English poetry, particularly modernists

such as T.S. Eliot.

After graduating with a degree in literature, Chen was assigned

by the government to the Shanghai Police Bureau as a detective

and is now an Inspector in charge of the "special case squad"

which investigates political crimes. Chen's job requires him to

perform a delicate three-legged balancing act: staying true to

his own moral guidelines, staying on the right side of the

party, and staying alive - a challenging task considering the

well-connected villains he tracks down.

The consistent characters in the series are Chen; his partner Yu

Guangming and Yu's wife Peiqin, and Yu's father, a retired cop

named Old Hunter who, in the first book, ekes out his existence

on a tiny government pension but, in the second book has been

given the honorary, and salaried, role of traffic advisor by

Chen. Such nepotism may not sit well with readers brought up in

the West, but the reality for Xiaolong's characters is that to

fail to take advantage of the system to help a friend would

simply be folly, and their manipulation of the system is

entirely inconsequential compared with the corruption of the

many senior officials ("red topped rats") who liberate multiple

millions from the system to line their own pockets.

A Case of Two Cities fits into the police procedural

genre (known in China as "legal system mysteries") but the

atmosphere and insider viewpoint of modern-day Chinese culture

and politics puts it head and shoulders above the average

detective mystery.

Like P.D. James's Adam Dalgliesh, Inspector Chen is a poet; he

also earns a little money on the side translating Western crime

fiction into Chinese. To Western readers it might seem

implausible that Chen could be a poetry spouting cop, not to

mention that virtually everyone he meets of his generation is

also able to quote Confucius and a multitude of proverbs and

poets. However, in an interview at

JanuaryMagazine.com, Xiaolong explains that "most novels in

China contain much more poetry [than Western novels] .... at the

start of the chapter, at the end, and in the middle -- and

sometimes they use a poem to introduce a new character." So he

has tried to keep this tradition in his writing.

Xiaolong goes on to observe that not only can poetry be a way to

discreetly reveal a person's character, but that China has a

self-effacing culture in which, sometimes, when it is difficult

to say something in prose, people will fall back on poetry.

This circumspection is one of the many charms of A Case of

Two Cities. There is a formality to the language that is

very appealing; threats are couched in such graceful language

that it's doubtful whether a generation of Westerners brought up

on a diet of sound bites would even realize that they were being

threatened if so addressed!

On reading A Case of Two Cities one becomes conscious of

how muddied is the line between honesty and dishonesty in

countries such as China, Russia and India (as seen in

Sacred Games) where the economies are growing at such a

great rate that the opportunities for corruption are

overwhelming at many levels of society. It could be argued

that, in such a climate, it is not possible to remain strictly

honest to the letter of the law, and thus it is up to the

individual's own conscience to toe that very fine line between

what is morally right and wrong. Inspector Chen's awareness of

this quandary and his desire to do the right thing, coupled with

his frequent revulsion at his occupation, are what make him a

truly noble figure. The potential for corruption is constantly

presented to him like tasty dim sum, but he resists, even though

so many around him are gorging themselves on the opportunities.

Qiu Xiaolong (pronounced "chew-shao-long")

was born and raised in Shanghai. He

managed to avoid the worst of Mao

Zedong's Cultural Revolution by falling

ill with bronchitis at the age of 16, so

he was able to stay in the city while

his peers left to be "re-educated" in

the countryside. One day while sitting

on a bench in Shanghai's Bund he noticed

some people studying an English

book, which was the start of an interest

that grew into an academic specialty in

modernist poetry.

He came to the US in 1988, at the age of

about 30, on a Ford Foundation grant.

He chose to study at Washington

University in St. Louis, Missouri,

because of his enthusiasm for the poet

T.S. Eliot, who was brought up in St

Louis before emigrating to the UK at the

age of 25.

Following the Tiananmen Square massacre

he decided not to return to China and

instead managed to extricate his wife,

Wang Lijun. Today they live in St Louis

with their daughter, Julia.

Useful to know

In Chinese the family name comes first, e.g. Chief Inspector

Chen Cao's family name is Chen, his given name is Cao. However,

the author's name has been "anglicized" on the book jacket so

that Qiu is his given name and Xiaolong his family name.

Interesting Links:

Series Order

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2007, and has been updated for the

October 2007 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in February 2007, and has been updated for the

October 2007 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked A Case of Two Cities, try these:

by Qiu Xiaolong

Published 2022

The legendary Judge Dee Renjie investigates a high-profile murder case in this intriguing companion novel to Inspector Chen and the Private Kitchen Murder set in seventh-century China.

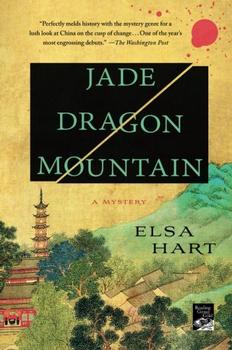

by Elsa Hart

Published 2016

On the mountainous border of China and Tibet in 1708, a detective must learn what a killer already knows: that empires rise and fall on the strength of the stories they tell.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.