Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Beyond the book | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

A Novel

by Brian HallThis is one of the best novels I've read in a

long time. It is hard to imagine gleaning more pleasure

from a book than I did from Fall of Frost - a novel that works on every possible level. For its

too-short duration, I was completely immersed in its world,

the emotional landscape of Robert Frost. Yet I also read it

with enough critical distance to marvel, open-mouthed, at

the skill with which Brian Hall constructed the book.

Fall of Frost is a character study in the deepest sense,

a spelunking into the psychological ferment behind Frost's

poems. And it is simultaneously an extremely sophisticated

meditation on literary form: a novel about poetry which is

itself built like a series of exploded and distended poems;

an exploration of the writing process that arises from

sensitive readings of Frost's work; a fictionalized

biography which puts the artificiality of its own method on

display (making it an implicit antidote to this tiresome era

of the false memoir). And to think that Hall did all this

with one hand tied behind his back, prevented by the Frost

estate from reprinting any of the poet's later work.

Hall makes transcendent art from Frost's melancholic mind

the way Frost himself made poetry from the many tragedies of

his long life. He locates the dark center of Frost's work in

his relationship with his wife Elinor. Beneath even the

horror of losing four children and committing both his

sister and his daughter to mental hospitals lay the

inexpressible sadness of his failure to connect with the

woman he loved so much. Every poem he wrote was for her.

Hall writes, "Once a poem pleases her, he doesn't want to

hear a peep of complaint from anyone else. It's her

poem, and don't you say a word against it." Yet their

marriage broke when their first-born son Elliot died at age

four, and Frost's every attempt to reach out to Elinor hurt

her more. Hall figures her as Eurydice to his Orpheus, slain

by his art but whose suffering only spurred him to yet more

generative outpourings of poetry.

And then there is the "wonderfully true" fact that on the

same day in 1962 that Nikita Khrushchev met with Robert

Frost in a dacha on the Black Sea, he also gave the order to

supplement the intercontinental ballistic missiles he had

sent to Cuba with nuclear warheads, and then retired to a

beach chair to listen to a minion read One Day in the

Life of Ivan Denisovich. This curious, little-known

episode from the very end of Frost's life captured Hall's

imagination and he uses it as a delicious counterpoint to

his portrayal of the private Frost. What was America's

foremost poet doing in that dacha? What did he have to say

to the crazed leader of America's sworn enemy? Frost's

improbable mission was at once political—to suggest a

solution to the crisis over Berlin—and poetical. Cultural

differences aside, Robert Frost felt enormous kinship with

the "ruffian" in Khrushchev but also saw something higher in

him. "It's that part that Frost must appeal to, the imperial

side. Make him see his greatness, seize it, become it. Dream

him into being, as a true emperor." He failed utterly.

Hall's causal connection between Frost's visit and

Khrushchev's order for nuclear weapons may be speculative,

but President Kennedy's irritation over what he perceived to

be Frost's bumbling of a diplomatic mission was real and

deeply hurtful to the poet.

Hall raises such speculation to high art. His novel gets at

Frost's character not with the certainty of the biographer

but with the elliptical suggestiveness of the poet. Each

short chapter revolves around a single scene, and Hall

builds into each one circulating motifs that eventually

settle into stately patterns. Here, in miniature, is an

example of the kind of convergences that go into the making

of one of Hall's chapters and one of Frost's poems. Frost is

talking a walk through Amherst in 1934, kicking up dead

leaves and thinking of his daughter's death in childbirth.

He looks with impatience and disgust at the sea around him of dead and dying leaves, and a new word occurs to him: ‘autumn-tired.' He remembers a dream he had a few weeks ago, about a plane. ‘Falling leaf.' He thinks of Margery, and his heart flutters like a leaf on a branch, wind-shaken, threatening to let go….He opens his eyes; kicks his way homeward. The sun is setting, and he's got a poem to write.

The poem to which Hall refers is 'A Leaf

Trader' ("All summer long I thought I heard them whispering

under their breath / And when they came it seemed with a

will to carry me with them to death"), which Hall is not

allowed to quote. But he has intimated it to me and infused

it with life, and I feel replete.

Terrible punning title (which comes from an Emily Dickinson

poem). Even worse book jacket. Superb novel. Please read it.

![]() This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2008, and has been updated for the

April 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

This review was originally published in The BookBrowse Review in April 2008, and has been updated for the

April 2009 edition.

Click here to go to this issue.

If you liked Fall of Frost, try these:

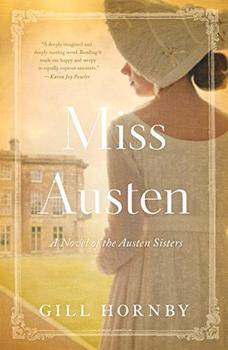

by Gill Hornby

Published 2021

For fans of Jo Baker's Longbourn, a witty, poignant novel about Cassandra Austen and her famous sister, Jane.

by Mal Peet

Published 2013

Can love survive a lifetime? With its urgent sense of history, sweeping emotion, and winning young narrator, Mal Peet's latest is an unforgettable, timely exploration of life during wartime.

Your guide toexceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.